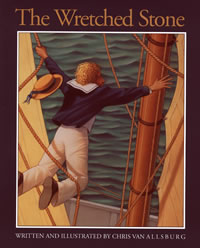

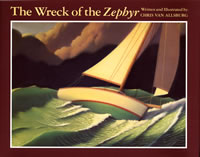

Part 2 of 2. In which the author discusses technology, magic, the inspiration for Queen of the Falls, and influences in his art and life. Part 1 is found here. Children’s books are the cornerstone of Center for the Collaborative Classroom’s (CCC) programs; in a way, the authors are our behind-the-scenes collaborators. We want teachers, administrators, students, and parents to be able to learn more about these wonderful authors. We are happy to present the third in a series of author interviews, with Chris Van Allsburg. Five of his books are used in our programs: Just a Dream, Probutiti!, The Sweetest Fig, and The Wreck of the Zephyr in Being a Writer; and The Wretched Stone in Making Meaning.

Children’s books are the cornerstone of Center for the Collaborative Classroom’s (CCC) programs; in a way, the authors are our behind-the-scenes collaborators. We want teachers, administrators, students, and parents to be able to learn more about these wonderful authors. We are happy to present the third in a series of author interviews, with Chris Van Allsburg. Five of his books are used in our programs: Just a Dream, Probutiti!, The Sweetest Fig, and The Wreck of the Zephyr in Being a Writer; and The Wretched Stone in Making Meaning.

CCC: The Wretched Stone shows the ripple effect of a screen-like object that numbs the imagination. You’ve talked about your lack of computer skills, yet your elegant website shows that you recognize how technology and book art can combine in a way that enriches both. At CCC, we’re studying ways to combine technology and learning in the classroom. What do you think about the role of technology in education? I have a sense that you do seem to recognize some benefits. I also wonder about it in your own life, with your kids, too. How do you handle the balancing of those things in your family?

Chris Van Allsburg: I don’t think technology is entirely a demonic thing. The fact is-this is a slightly separate issue, but if you’re reading text on a piece of paper, or you’re reading the exact same material on a glowing screen or on a Kindle, I don’t think on a neurological or intellectual level the experience is significantly different. What’s important is that you’re engaging your brain and absorbing the thoughts of another (assuming that what you’re reading is worthwhile). The act of reading that is taking place on these different devices is OK with me, and the reality is that the digitization of it is OK with me-if we’re simply talking about reading as an activity which can broaden people’s horizons, enrich their lives. But of course, a lot of reading doesn’t do that. Having said that, I have to say that in my own field, the digitization of the things I do-picture books-is brutal and incredibly destructive to the unique experience of holding different kinds of books. I’ve got tiny little books that sit in the palm of my hand, I’ve got big books. I’ve got books-I’m not talking about just the books I’ve made-in my library that you open up and there will be a very small picture with the text around it and you’ll turn the page and it’ll be a double-paged spread. Suddenly, it seems like the environment you’re in has instantly been broadened, emboldened. So these specific pleasures that come from the manipulation of scale that you can do in a paper book-and in the choice of format (for example, a tall, vertical book, like The Widow’s Broom or a very horizontal book like The Polar Express), they all get ground to digital dust and shoved into the same format with the same cruddy reproduction for the Kindle, the iPad-even the computer screen. It doesn’t matter how good screens get-they are not going to be able to reproduce the artwork as well as a good printer can reproduce it.The idea of having your entire library stored on any device is depressing. So much of a library has to do with the experience of picking up a book printed on a vellum stock that has tipped-in glossy pictures and is 12 inches tall and 9 inches wide…compare that to having everything crunched into the same size-how do I get to read it, or go from page to page? I push a button. I’m sorry, it’s not satisfying, and it also is a striking example of how technology can strip down life in a way that makes it less pleasurable, less rewarding, less varied, less tactile.What I’m saying is that while I believe the technology can be quite beneficial-it can teach you to play the piano, it can teach you how to speak French in ways that are probably efficient and effective-in the end, all the digitization is not leading to happier and better lives for a media-consuming culture.If we’re talking about textbooks and it means that kids in college can download them for $20 instead of having to buy their professor’s latest title for $150, I don’t have a problem with that. But nobody’s going to be able to build a wall between that kind of reading and the kind of reading that I’m involved with. As I contemplate the migration of my work off of printing presses onto servers, it’s a giant bummer.

Having said that, I have to say that in my own field, the digitization of the things I do-picture books-is brutal and incredibly destructive to the unique experience of holding different kinds of books. I’ve got tiny little books that sit in the palm of my hand, I’ve got big books. I’ve got books-I’m not talking about just the books I’ve made-in my library that you open up and there will be a very small picture with the text around it and you’ll turn the page and it’ll be a double-paged spread. Suddenly, it seems like the environment you’re in has instantly been broadened, emboldened. So these specific pleasures that come from the manipulation of scale that you can do in a paper book-and in the choice of format (for example, a tall, vertical book, like The Widow’s Broom or a very horizontal book like The Polar Express), they all get ground to digital dust and shoved into the same format with the same cruddy reproduction for the Kindle, the iPad-even the computer screen. It doesn’t matter how good screens get-they are not going to be able to reproduce the artwork as well as a good printer can reproduce it.The idea of having your entire library stored on any device is depressing. So much of a library has to do with the experience of picking up a book printed on a vellum stock that has tipped-in glossy pictures and is 12 inches tall and 9 inches wide…compare that to having everything crunched into the same size-how do I get to read it, or go from page to page? I push a button. I’m sorry, it’s not satisfying, and it also is a striking example of how technology can strip down life in a way that makes it less pleasurable, less rewarding, less varied, less tactile.What I’m saying is that while I believe the technology can be quite beneficial-it can teach you to play the piano, it can teach you how to speak French in ways that are probably efficient and effective-in the end, all the digitization is not leading to happier and better lives for a media-consuming culture.If we’re talking about textbooks and it means that kids in college can download them for $20 instead of having to buy their professor’s latest title for $150, I don’t have a problem with that. But nobody’s going to be able to build a wall between that kind of reading and the kind of reading that I’m involved with. As I contemplate the migration of my work off of printing presses onto servers, it’s a giant bummer.

“While I believe technology can be quite beneficial…in the end, all the digitization is not leading to happier and better lives for a media-consuming culture.”

CCC: Does Houghton Mifflin express some interest in doing that with any of your books?

Chris Van Allsburg: I think over the years most of my books will probably be available digitally. This last book, Queen of the Falls…I was going to say it lends itself [to digital conversion] because of its proportions, but the fact is, even though it’s a vertical book, which should work out, there are double-paged spreads which become horizontal. The technology doesn’t really suit the book design that I’ve accomplished.

CCC: It sounds like what you’re saying is that if people are discerning about how they use technology and don’t try to make it a one-size-fits-all solution, you don’t have an issue with it.

Chris Van Allsburg: I don’t. But I’m afraid that…You’ve already pointed out the power of economic forces. [See Van Allsburg interview Part 1] You can’t blame people if they have a certain amount of discretionary income and they want their child to have a particular title, and there’s already a device in the house, and they say to themselves, “Well, I can download it for 8 bucks, or I can buy the hardcover for 20. Gee, you know…Johnnie doesn’t seem to have a problem reading his books on the computer, we may as well just download that thing instead of buying him a book.” So there are economic reasons why people would do it and you can’t really find fault with them if it’s a way of getting the material, even digitized, into their child’s room. I guess that’s a good thing. It’s lower priced, it gives people access. At the same time, it points to the inevitable: the slow and painful death of the Gutenberg age.

CCC: How do you handle technology in your household, as a parent? Some of the things that have woven through your answers have to do with creating a space where you’re not inundated with outside culture.

Chris Van Allsburg: Here’s an interesting fact about my life. I am the only person I know over the age of ten who does not have a cell phone. My daughters both have cell phones, they’ve had them since their peer group required that they buy one. My older daughter, I’m happy to report has “de-Facebooked.” She got to college and she finally realized it was just gobbling up enormous amounts of her time and that as long as it was there for her, she was going to keep using it. She shared with her mother and me, “It’s just too much, so I got myself off.”

“If you never engage in the simple act of solitude and silence it means you’re never engaged in self-reflection.”

I don’t know if my younger daughter, at 16, has reached the same stage in her life yet. It’s too tempting to just plug into the social buzz, and hum along for hours at night because this social vibration is too satisfying, is too attuned to what the adolescent brain craves.

CCC: Then linking back to the very first question: It’s even more difficult to tune out your peers these days to create a separate space where you might write, for example. Trying to forget about other people for awhile and follow your own imagination.

Chris Van Allsburg: Exactly. I find that often people are enveloped by a “digital fog.” One of the results of this “fog” is you’re constantly in communication with other people, you constantly have your iPod on. If you never engage in the simple act of solitude and silence it means you’re never engaged in self-reflection, which means that you’re less likely to have a clear sense of your own identity. I encourage my daughter to keep a journal so that she has a place to reflect on what’s happened in her day. I think for this generation, it’s possible to literally go for days and days without metaphorically looking in the mirror because they have constant stimulation. It imperils their maturation.

CCC: In Just a Dream and The Wreck of the Zephyr, the protagonists display character flaws: hubris for the boy sailor in The Wreck of the Zephyr, and laziness for Walter in Just a Dream. But the narratives offer no outright judgment. Instead they allow room for the readers to reach their own conclusions about the characters. You seem to harness the power of what is left unsaid. How do you decide what to leave out of your stories and illustrations-if you do that at all? It may be that you create them as is.

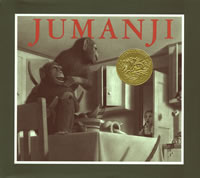

Chris Van Allsburg: Oh, no. That was something that I did unintentionally in my very first book [The Garden of Abdul Gasazi] in which there’s a young boy who has an experience with a magician. The experience he has requires that he make a decision in the final pages of the story. Namely, was he exposed to the trickery of a stage magician, or was he exposed to the real magic of a wizard?When I got to that point in the writing, I realized that I had actually finished the story. That I didn’t need to make a decision because the story was much more interesting to me right at that point. The boy has found something at the very end of the story that instantly poses the question: Did real magic happen or did someone trick him? The boy happens to be about 11 or 12, and that’s right about the point where children start to wonder, can magic really happen or is it just tricks people do that make us think the miraculous can happen? There was a child protagonist in the story, a child reader would identify with him, and that child reader would be on the last page with the boy, whose name was Alan, wondering if magic can happen, if miracles can really happen, or if when we see the miraculous, we have just been tricked.That’s a great place for a book to end because the narrative is completed, but the story is not done until the individual reader actually makes a decision on their own. I was lucky to have an editor for my first dozen or so books at Houghton Mifflin, a distinguished editor who’s retired-his name is Walter Lorraine-Walter was so supportive. He never said, “Oh, these drawings have to be in color,” or, “This story has to have an ending on it.” He encouraged this idea that it could be just what I thought it ought to be because I was the artist, and that was great.When I finished that story, I said, “I think the story’s done.” And Walter said, “I think it’s done if you think it’s done,” so that’s where it was. In that first book, I left something out. I thought the book benefited from it because it became more of a mystery. As I said, I love the idea that the narrative could end but the story didn’t-even when you closed the covers of the book. That seemed to me to be a powerful thing that a book could do. In a slightly more calculated way, I also did that in the second book, where I suggested that the story the reader had just read, which was Jumanji, was about to happen again, but because of what we learned about the next set of players, we could imagine that the game would have a different outcome. For years and years, everyone said, “That last page-there’s a sequel. No one would write that page without the intention of doing a sequel.” I never had the intention of doing a sequel but I knew that it would inspire my readers to contemplate the fate of Walter and Danny, who are introduced on the final pages, and to wonder what those characters’ experience would be like. Just like the first book-I liked the idea of the narrative concluding, but once you close the covers…I know that parents read books to their children at night to get them to go to sleep. I liked to imagine a parent reading Jumanji or Abdul Gasazi to their child, closing the book, turning off the lights, and the child is wide-eyed, trying to figure out what happens next. Or in the case of Gasazi-what really did happen? I am attracted to the idea of seeding the imagination by leaving a little something untold.

For years and years, everyone said, “That last page-there’s a sequel. No one would write that page without the intention of doing a sequel.” I never had the intention of doing a sequel but I knew that it would inspire my readers to contemplate the fate of Walter and Danny, who are introduced on the final pages, and to wonder what those characters’ experience would be like. Just like the first book-I liked the idea of the narrative concluding, but once you close the covers…I know that parents read books to their children at night to get them to go to sleep. I liked to imagine a parent reading Jumanji or Abdul Gasazi to their child, closing the book, turning off the lights, and the child is wide-eyed, trying to figure out what happens next. Or in the case of Gasazi-what really did happen? I am attracted to the idea of seeding the imagination by leaving a little something untold.

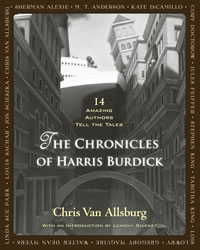

CCC: You’ve led beautifully into my next question: The ultimate example of leaving room for the reader’s imagination is The Mysteries of Harris Burdick, in which the 14 images present the illustrations and captions from missing stories which are left for the individual imagination to explore. I wonder what you make of the impact of this book. Not just all the stories that you’ve received from kids, but also the Stephen King short story, and I saw that Burdick was also turned into a musical, and there’s more, too.

Chris Van Allsburg: Yes, there’s a new edition called The Chronicles of Harris Burdick, and Houghton Mifflin invited-since they knew of the Stephen King story and were able to secure the rights to it-they invited 13 other authors to choose a picture and write a story. It’s quite a distinguished list of Newbery winners and other very accomplished writers. This book is being published in the fall [publication date October 25, 2011], so people will be able to read what some experienced storytellers have done with the pictures, titles, and captions left behind by Burdick.

CCC: It’s a fabulous concept-it’s very evocative and I can imagine kids sitting up at night thinking about some of those pictures. Especially the one where the boy is sure he sees the doorknob move. Moving on to Queen of the Falls appears to be a departure, but I don’t think it is, really. It’s a mirror image of your other work, and it seems to me that instead of creating an imaginary world that hovers on the edge of believability, you’ve re-envisioned a true story strange enough to be mistaken for fiction.

Chris Van Allsburg: I appreciate that observation because it is a little bit like what I described before. You get one wild card to play, and Annie plays hers. She’s the joker. I read about her many, many, many years ago in a Sports Illustrated article. I can remember where I was when I read it. I was working at a summer job in a little factory. There was a lunchroom with a pile of old Sports Illustrated magazines. I read in an article about daredevils that the first person to go over Niagara Falls in a barrel was a 62-year-old woman. I thought at the time: Well, I should’ve known that. I’d gotten a decent education. How did I get to be 22 and not know that? Here was some kind of tall tale that was actually true. That 3rd, 4th, 5th graders weren’t exposed to this bizarre little chapter in American history seemed wrong to me.The story of Annie Taylor fell into the recesses of my memory. Forty years passed and about a year-and-a-half ago I was interested in working in what I thought would be a different genre, and I’ve always had affection for these books that are seemingly about an individual but they’re also, to a large extent, stories about America itself. I thought I would like to do a book like that and I wondered who might make a good subject. There are so many books of this kind that follow the exploits of characters in America’s history, I wanted to find an individual whose story was obscure. Then, I remembered: Oh, yeah…the woman who went over the Falls in a barrel. She would be a great subject because that’s just too strange and too weird. Forty years had passed and I still hadn’t heard of her. She still hadn’t become what I thought should be part of Americana.So I thought I was going to have to do some really arduous and difficult research, that I was going to have to call Time Life to see if I could find the old Sports Illustrated magazine. How was I going to find out about this woman? Then it occurred to me I could just Google “woman, barrel, Niagara.” And so I did that, up she popped, Annie Edson Taylor. I was a little disappointed that she was not really truly obscure, but I realized at the same time, with regret, that there is no such thing as obscurity anymore in the age of the Internet.I went through the information, delighted to find out that no one had actually made her the subject of a mass market published book. Somebody had written a monograph, a woman had written an epic poem in the voice of Annie Taylor. There were four or five books I was able to get from my library that were about Niagara Falls that included information about Annie Taylor. I was able to collect a fair amount of information. I actually discovered what was, to a point, a fairly inspiring story, but past that point, a story that is somewhat melancholy. It’s not a tale of a sympathetic underdog triumphing against all odds and finding the rewards she deserves. It didn’t fit that description. In some ways maybe it’s good that it didn’t because if that was the outcome, it would have been a more conventional story than I am interested in telling. What I discovered was that the rewards and economic benefits that Annie thought would come to her as a result of her achievement did not. She was victimized by her managers, and, because she billed herself as a 42-year-old adventuress, when audiences arrived at the lecture halls that she went to-in order to capitalize on her achievement-they would see this 62-year-old woman, which in 1901 is more like a 78-year-old woman. They couldn’t believe it. She didn’t look like a daredevil, she looked like someone’s grandmother.It wasn’t that they thought she was a fraud, it was just the cognitive dissonance that they had to confront, which was that they’d read about her bravery, her vigor, and her age. She falsely claimed she was 42. I think she understood that people would be more interested in a younger heroine. But when they got to these lecture halls and they saw that she was not a dynamic stage presence and that she lacked the charisma and vitality they expected to see, the lecture tour became a bust. She had her original barrel stolen, recovered it, but had it stolen again. She finally had to settle for just selling postcards near the Falls-with a second barrel she had made just as a prop so that people would come and visit her souvenir stand.She lived to be 82. She wasn’t badly injured in her trip over the Falls, but obviously it could’ve ended her life at 62. She lived for 20 more years after her big plunge, so she was from hearty stock. A person of 82 in 1922 was of very advanced years.

In some ways maybe it’s good that it didn’t because if that was the outcome, it would have been a more conventional story than I am interested in telling. What I discovered was that the rewards and economic benefits that Annie thought would come to her as a result of her achievement did not. She was victimized by her managers, and, because she billed herself as a 42-year-old adventuress, when audiences arrived at the lecture halls that she went to-in order to capitalize on her achievement-they would see this 62-year-old woman, which in 1901 is more like a 78-year-old woman. They couldn’t believe it. She didn’t look like a daredevil, she looked like someone’s grandmother.It wasn’t that they thought she was a fraud, it was just the cognitive dissonance that they had to confront, which was that they’d read about her bravery, her vigor, and her age. She falsely claimed she was 42. I think she understood that people would be more interested in a younger heroine. But when they got to these lecture halls and they saw that she was not a dynamic stage presence and that she lacked the charisma and vitality they expected to see, the lecture tour became a bust. She had her original barrel stolen, recovered it, but had it stolen again. She finally had to settle for just selling postcards near the Falls-with a second barrel she had made just as a prop so that people would come and visit her souvenir stand.She lived to be 82. She wasn’t badly injured in her trip over the Falls, but obviously it could’ve ended her life at 62. She lived for 20 more years after her big plunge, so she was from hearty stock. A person of 82 in 1922 was of very advanced years.

CCC: As they become more sophisticated readers, children tend to leave picture books behind. And yet your books are mainstays of our programs at 5th, 6th, and 7th grades. Why do you think your books resonate with kids of all ages?

Chris Van Allsburg: I remember mentioning my first book to someone and they said, “Oh, well, I guess you’re working from the vocabulary list then.” And I said, “What does that mean?” “Well,” they’d continue, “Don’t you get a vocabulary list from publishers when you’re writing for a certain age group? You have to stay within that so kids will understand.” I said, “Gee, I don’t have a list.” They said, “I’m sure they’ll edit it for you when they get it,” but they didn’t.That first experience set a pattern which was that I never thought very much about the age of my audience. I knew that for the most part, it would be on the younger side. But I always thought that even if I used a word that made them reach a little bit, they could figure it out because of the context or the picture. I am always very careful to write lucidly-to not write compound sentences, where the meanings get stacked up on top of one another. I committed myself to writing in a fairly straightforward and simple style. I never felt the need to write down to or pander to or wonder whether or not my subject matter was too big a reach for my audience-never gave that a thought-I just set out to tell a story as well as I could.I can communicate with kids through speech, so I saw no reason to greatly alter the way I communicated with them when writing. I think the result of this is that I’ve never talked down to my readers. I’ve never come up with an idea and then discarded it because I wondered, “Gee, can I express this in a way so kids will understand it? Is it too complicated? Too sophisticated?” I think as a result the stories don’t seem as age-specific as a lot of picture books and that may be why even middle-schoolers still get some pleasure from reading them.

CCC: They remind me of the Miyazaki films.

Chris Van Allsburg: I am familiar with his work and Spirited Away is one of my favorite films.

CCC: One of mine is My Neighbor Totoro.

Chris Van Allsburg: I also have Kiki’s Delivery Service. I loved watching that with my daughters.

CCC: The films are very magical like your books and they don’t leave out adult concerns. It’s just like being part of a family: when there are issues and hard times they are all part of the mix for the kids as well as the adults.

Chris Van Allsburg: I’m a great admirer of his work.

CCC: Can you tell me what you’ve read lately that you really loved?

Chris Van Allsburg: I’m about a third of the way into Room now, which I like very much because it shows such an acute understanding of the way a child’s imagination works. It’s a fairly horrific story, but that horror exists, I wouldn’t say subtextually, but it’s woven into the story. But the idea of imagining a world within a room somehow just connects with memories of my own childhood. Of course I never felt I was confined to my room for a long period and had it imposed on me, but the way Emma Donoghue created the child’s imagination and how the room functions as a world-putting aside the context or the circumstances of the boy and mother’s confinement-that’s really the thing I find the most satisfying. It’s the creation of a world within a room. It’s like playing with a dollhouse.

“The reality is that in nearly every piece of work…there is something that’s worthy of praise and it’s important to identify it.”

CCC: Sharing ideas with classmates and giving feedback on each other’s writing are important parts of the process in our Being a Writer program. How do you work with your editors, and others, and what do you find rewarding or challenging about that process?

Chris Van Allsburg: I have to say that my editor was very laissez faire. With me, he had a very free hand, so it’s hard to find a model in that working relationship that would answer this question. I did spend ten years teaching at the Rhode Island School of Design, and the “critique” was for me the most important part of teaching. It would always be at the start of the class, it would require that all the students tack their work up to a large bulletin board-the whole wall was a bulletin board, so the whole wall of the classroom would have artwork on it and the class would gather in a small group, maybe 20 students, in front of me.The crit was very important because I feel that a lot of the learning that goes on about making art-and I think it’s probably true about writing as well-is forming opinions about it. So of course, while creating a piece of art you’re constantly forming an opinion about it because you have to develop it and you have to make many decisions as you’re doing it. It’s a process filled with stimulus/response. The stimulus being: Here’s my idea, here’s the thing I make. The response being: Now how do I feel about having put it down on paper, or on the screen?I thought it was just as important for students to be able to look at work on the board-not their own work-and be able to identify what they thought was successful about it and what they thought was not successful about it.The critique could accentuate the reluctance of my students to speak. They were emboldened as they got to be juniors and seniors, I think just because they became more confident in their own judgment. The younger students that I sometimes taught found it difficult to be critical of their peers. They wouldn’t share their ideas-they would share their positive ideas, but they wouldn’t share their negative ones-and I felt very strongly that the ability to discern what in a drawing or a sketch, painting, poster was good and what was bad was very important. So the first couple of weeks, it was up to me to point out-because the students didn’t want to do it-what I thought was or was not successful in a particular piece.The reality is that in nearly every piece of work, even if it isn’t particularly successful, there is something that’s worthy of praise and it’s important to identify it. But then in the less successful work, you have to spend more time on the things that aren’t effective. Still, you try to build on the little thing that is positive and say, “If you’d been able to maintain what was going on in this part of the picture and this part of the picture, the whole thing would’ve been more successful.”I felt strongly about the crit because it refined the judgment of all the students in the class. Not only when I called upon them to make an appraisal of a particular piece, but because they were listening to other students do it, they were listening to me do it. I think some of them were probably impatient because it’s a visual art form–“How important is this?” “Do we have to talk about it?” I really believe in the power of articulating your ideas as a way of establishing them in your head so that they become part of your visual vocabulary.By talking about it, by looking at it, by speaking the words out loud-Why does this composition not work? Why is this object in the wrong place?-then getting them to actually be able to articulate why that’s problematic. It’s just as important an educational experience as doing another drawing. They saw it, they judged it, and they learned it.I’ve never taught writing and I’m not sure if it would work exactly the same way in a writing class, but I think there’s probably value in it. Some assignments I gave did require writing. This was in a specific class I created called “Design Your Own Country.” The students in this class had to make a travel poster, do a stamp design, design the currency, do a portrait of the monarch or president (whatever form of government it had), keep a sketchbook, and also keep a journal of their experiences while they were visiting the country. So occasionally I asked them to read from their journal entries about visiting this mythical country they’d created.I discovered that for an artist, language is more personal than picture-making. You’d think it’s probably not that way, that with language you can conceal yourself, defend yourself, put up a screen in ways you can’t when you have to draw the picture, because when you’re a visual artist, you’re bound to expose yourself through your art. But I found even in a group of visual artists that language left them feeling more exposed and vulnerable than the pictures they made.

CCC: In one of your Caldecott medal speeches, you said the success of art is not dependent on its nearness to perfection, but its power to communicate. This is a wonderful model of the type of learning CCC embraces. We publish programs that foster classroom communities in which students do a lot of the communicating as opposed to the teachers. The goal is for them to know how to articulate opinions and ideas and feel safe sharing them. Success for students and teachers is defined by learning and individual growth rather than being “right” or perfect. Based on your experiences as a student and as a mentor and teacher, what is your reaction to that approach?

Chris Van Allsburg: It seems like a sound one. I have stressed through most of our conversation that the creative process is fundamentally a solitary activity, or at least derives its power from personal ruminative and reflective efforts. However, for those unaccustomed to the work, especially at a younger age, functioning among a peer group eager to share ideas with one another can be a stimulation that produces individual imaginative impulses.What I was wondering about in that speech was the idea that there is such a thing as a standard [of perfection], but I concluded that there is no such thing as perfection in art because its power, its virtue, is the ability to communicate or stimulate feelings and ideas. Some kinds of art communicate very strongly to certain people and don’t communicate at all to others. So if you say, we’re judging art based on its power to communicate, and some people are unmoved by it entirely, and some people are greatly moved by it, then how can we judge art?-if we’re going to do so based on that potential to communicate?I’m uncomfortable in some ways saying this, but where you end up is that you can’t really qualify art. You can’t judge art because sometimes it does communicate to some people and fails to communicate to others. And if you say, “Well, you can’t judge art,” and if that includes painting and sculpture and pictures, then how can we have discernment or criteria that allows us to determine what is good and what is not good?

“There is no such thing as perfection in art because its power, its virtue, is the ability to communicate or stimulate feelings and ideas.”

How do you know what belongs in a museum? How do you know what’s valuable and what’s not valuable? I’m not sure I know the answer to the question. I’d be happy to be put in charge and tell everybody what’s good and what’s bad. The fact is, we have institutions in the culture that do that. There are art galleries. Those galleries are run by knowledgeable and sophisticated people. They have wealthy collectors who will come in and those people will buy the art. As the price and desirability of that art goes up, because certain collectors have begun to collect it and certain dealers are very enthusiastic about it, then the culture starts to understand, “Well, maybe this is good,” but in a funny way, the judgment at that point has not been made purely on a power-to-communicate basis, it’s been made based on a lot of cultural factors that are only tangentially connected to art and communication.

CCC: It’s also interesting to think about the artists who weren’t able to communicate with the people of their own time and have only become beloved and admired by later generations.

Chris Van Allsburg: Van Gogh is the prime example of someone whose art is treasured beyond almost all other painters but who was dismissed during his lifetime.

CCC: In life and in art, you playfully explore the line between the truth and fiction-your finagling your way into art school and the elaborate Mysteries of Harris Burdick are just two examples. Did you grow up in a family of storytellers or jokesters? How did magic play a role in your childhood?

Chris Van Allsburg: Well, it didn’t. I don’t want to diminish my parents in any way by describing them simply as conventional. They were extraordinary because they were mine. My father’s still living. My mother’s been deceased for some years. They both to me are unique and in some ways exceptional individuals, but from a distance, as seen outside the family, I would say they might appear to be fairly conventional. My mother probably less so, but neither of my parents were artists. My mother was in a way, but she expressed it through her home. She was very, very particular about the objects, the furniture, the décor of our homes. And she had a real belief in the power of your surroundings to establish a sense of well-being or at least a sense of contentment, because when you’re surrounded by particular kinds of objects they can affect your emotions. If you make the right choices, you can create an environment that will constantly comfort and console, provide solace, and give you a feeling of domestic security. These are lessons that I learned from my mother and I really absorbed them. The idea that you can create a chamber that has things placed in the right place, that are the right size, color, finish; that you can create a theater inside your home that will make you feel a particular way about your life and yourself. That’s a kind of a magic. My mother believed that.

CCC: Did you play practical jokes? Or are you doing all of that in your fiction?

Chris Van Allsburg: I like the idea of them, and I like movies that trade in that-movies and TV shows that I watched as a kid that traded in elaborate illusions. I remember being a pretty big fan of Mission Impossible, which always accomplished its narrative goals by creating these alternate realities to persuade their mark or target that a certain reality existed that did not. This, in turn, induced the mark, the target, to behave in a certain way or say or do something that solved the problem.

CCC: What about The Twilight Zone?

Chris Van Allsburg: Rod Serling. People ask me: Are there any authors that influenced you? He’s actually the only one I can think of. He didn’t write books or at least I haven’t encountered any, but the teleplays he wrote were fabulous. I don’t think I was especially young when The Twilight Zone was broadcast, I was an age-appropriate viewer, but I was also a somewhat timid child. Some of them were scary for me, but others were really fascinating. I liked The Twilight Zone.I can’t sense it directly-I’ve never sat down to write something and had in mind any episode of The Twilight Zone, but I believe that my exposure to the show shaped my storytelling impulses and my imagination.

CCC: I hadn’t thought about it before, but now that you’ve talked about having your one joker and everything else be somewhat realistic in your stories [see Van Allsburg interview Part I]-that’s similar to The Twilight Zone.

Chris Van Allsburg: It is. People have described Hitchcock’s work as a little bit like that as well. A normal man will have one extraordinary thing happen to him. The normal man-the average man-will have to cope with this single extraordinary experience and follow where it leads him.I was trying to think of other elaborate hoaxes. I can remember some in films that I saw at an age where their formative power on me was probably not great, including a couple of David Mamet films. One was The Spanish Prisoner, and another was The House of Cards, and also a classic, The Sting, which was much more of a pop-culture film, but I do like that story model of creating a completely bogus and highly detailed reality for some benighted character.

CCC: Lastly, could you describe one of your memorable teachers?

Chris Van Allsburg: I had a memorable and inspiring instructor at the University of Michigan who taught a course called “Light and Motion.” It might be surprising because I ended up getting my degrees in sculpture where you’re making objects. I worked in a fairly traditional way-carving wood, casting bronze. I did that as a graduate student and went on to doing pretty concrete things, continuing to make sculpture and ultimately drawing pictures and making books. This teacher of “Light and Motion” was an instructor of “conceptual art,” which had a lot more to do, I suppose, with ideas about illusion, and magic, and contemplating the reality of things that weren’t really there. The professor, whose name was Milton Cohen, encouraged us to make musical instruments, we wrote small dramas, we did a little bit of theater. He had a curriculum that invited students to use all parts of their imagination. Even though I’m in some ways a very conservative person and I loved hiding in my little corner of the woodshop and making well-crafted objects, I responded strongly to this teacher’s curriculum that mixed musicianship-I wasn’t a musician, but I ended up building musical instruments and scoring pieces for them-with theatre and performance art. Some of the projects were collaborative, which was something I hadn’t done as an artist and haven’t done since, really. I did learn from other teachers and I was supported and encouraged by them, but it was this class, “Light and Motion,” that awakened something in me, and it made me sense the magic that is an important part of art.