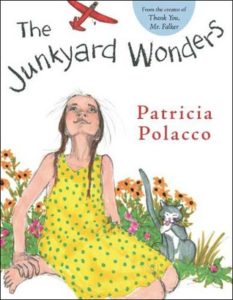

Children’s books are the cornerstone of many Collaborative Classroom programs; in a way, the authors are our behind-the-scenes collaborators. We want teachers, administrators, students, and parents to be able to get to know these wonderful authors and illustrators, so we launched a series of interviews a few years ago. We are now delighted to share a recent conversation with Patricia Polacco. Many of her books are part of our programs and libraries: Chicken Sunday in the Making Meaning program, and Thank You, Mr. Falker, Meteor!, and Still Firetalking in the Being a Writer program, to name just a few.

“Everything that I have learned that’s valuable came from stumbling and falling flat on my face, and clawing my way back up again.”

CCC: Your family spent a lot of time doing what you call firetalking. Your grandmother telling stories in front of the fireplace, while you and your brother nibbled on popcorn and apples. When asked if the story was true, she would say, “Of course, it’s true but it might not have happened.” You’re the firetalker now.

Polacco: Yes, I am.

CCC: Could you share some thoughts about your grandmother’s answer, and how her truth applies to your own stories?

Polacco: Well, there is truth and there is “truth.” If you’re looking for dead-on accuracy in the recounting of events, I think that is not the purview of a storyteller. A storyteller is certainly going to embroider and add things that are exciting and amazing. My father’s mother was Irish and my mother’s mother was Russian; both of those cultures rely heavily on relating to the world as we know it through tale and story. To answer your question, I guess I would have to say I think all of us have our own truths. There are some that are universal—that all humans feel. Then there are some truths that are stretched and pulled and molded to suit a personal family story.

CCC: Speaking of your Irish grandmother, you said in Fiona’s Lace, “It’s in your heart home resides, and it will remain there as long as you remember those you love.” You’ve done an amazing job remembering those you love through words and pictures. How do you decide which story you’re going to tell? Is there a story you’ve wanted to tell, but haven’t quite figured out how to write yet? I have this idea of you sitting in your rocking chair in the morning…

Polacco: Oh, that’s exactly what I do, sipping a cup of tea. I do my hardest work actually while I’m rocking and thinking. As a young person, I had “failure of sensory integration.” I have to move in order to think, and rocking is the most splendid way of having movement when your mind is racing. I used to go for long walks, and think up incredible ideas and stories. I’ve got millions of them. In a way, they take on a life, they tap me on the shoulder and decide what is coming next. I could be influenced let’s say by current events, or I can have something happen in my life that will bring up a story and then I’m thinking, “Oh my god! Oh, that’s something I want to write about.”

A story that I recently sold to Simon & Schuster is a typical example. The working title is Sissy Boy, and it’s about a boy I went to school with in Williamston, Michigan, that one year I spent there. What he [Tom Schoff] and I had in common is we both danced and took ballet. He was tortured by children because he was very effeminate. I just adored him. I remember what he taught me. At the end of the year, there was a talent show, and Tom decided to do Prince Siegfried from Swan Lake. He came out on the stage and he was catcalled and booed, but then he started dancing. Somebody took the record off and all you heard were the pads of his shoes, his feet, as he hit the floor doing perfect changements [a jump in which the feet change position in the air.] He was elegant. One person started clapping. Then pretty soon the entire auditorium burst into a standing ovation for him. And that single incident taught me about grace under fire. Now that boy lived most of his teenage life in that small town, Williamston, Michigan. Thom went on to become the… I guess, artistic director for the American Ballet Theater in New York.

CCC: All it took was one person to start clapping, which is a lesson for us.

Polacco: There you have it, one person clapping. Absolutely.

CCC: Three of your books, Still Firetalking, Meteor! and My Rotten Redheaded Older Brother, are the foundation of the first lessons in our grade five Being a Writer curriculum.

CCC: Three of your books, Still Firetalking, Meteor! and My Rotten Redheaded Older Brother, are the foundation of the first lessons in our grade five Being a Writer curriculum.

Polacco: Oh great!

CCC: Yes, your books are very important to the lessons in the beginning of grade five. We focus on students getting ideas from their own lives and suggest the class invite older family members to visit—building on your intergenerational family stories. But even when students have ideas about what to write, putting those ideas into words can be intimidating. Maybe they’re afraid of not being good enough or smart enough or of being different. What advice can you offer students and their teachers about how to tell their own stories?

Polacco: I think kids are afraid of making a mistake. I think they should have the freedom to just get it all out on the paper in their own words. Don’t pay any attention to its form, spelling, or anything else. People get so caught up in having the absolute perfect phrase that they get stuck and nothing gets written. You can go back and make all kinds of corrections, but initially, just literally let it pour out. And once you have that pitcher starting to pour the water, the water just empties out. It’s like giving birth; there’s nothing you can do to stop it. Once the labor has started, that baby is going to come.

I think stories start at the heart and end with the heart—they make a circle—so that the ending and the beginning all have the same source. I think that’s what makes the story authentic and that’s what makes it come to completion.

So offer the freedom to pour it out, and also try to keep the focus very small so that children don’t go way, way out there and can’t find their way back. A good way for teachers to help kids write is to put objects out on a table and ask kids to look at them—pick one, pick them all if you like—and write something about all the things that can be done with the objects, except what they are actually supposed to be used for.

CCC: I think you wrote about that in An A From Miss Keller?

Polacco: Right. And that was brilliant because it makes you start thinking outside of the box. Also encourage children to write about something that’s bothering them, or write about something that makes them so happy. I think if you start from an emotional standpoint, you’re going to get some writing. When I do school programs, one of the sections that I include is about bullying, and how I was teased and bullied and shoved around as a child. That elicits volumes of writing because there’s not a kid that hasn’t experienced it. I wish we lived in a world where we don’t have to experience it, but there we are.

Polacco: Right. And that was brilliant because it makes you start thinking outside of the box. Also encourage children to write about something that’s bothering them, or write about something that makes them so happy. I think if you start from an emotional standpoint, you’re going to get some writing. When I do school programs, one of the sections that I include is about bullying, and how I was teased and bullied and shoved around as a child. That elicits volumes of writing because there’s not a kid that hasn’t experienced it. I wish we lived in a world where we don’t have to experience it, but there we are.

So try to start at that emotional base, and I think students will climb the mountain and they will blow the socks off of their teachers.

CCC: You talked about starting and ending with the heart, and I had been thinking about the importance of the beginning and endings of stories, and what a major impact that has on the power of the story to engage and move the reader. How do you decide about your opening and closing sentences?

Polacco: I sit and rock here and go over and over and over it again in my mind, because the beginning is where you are setting the scene. Then somewhere in the middle of the story is the problem. Then the rest of the story is usually finding a resolution. The end is showing how the character is now changed and different from what they were before it began. Not beating the kids over the head with it, but by its example within the story, they will know, the reader will know, “Oh, they’re going be different now because this is what happened.”

CCC: In our Making Meaning lesson that is based on Chicken Sunday, we explain to the students that main characters often change over the course of the story after facing a challenge or a problem, just as you were saying. Could you tell us about a way that you’ve changed over the course of your life, and what conflict or problem spurred that change?

CCC: In our Making Meaning lesson that is based on Chicken Sunday, we explain to the students that main characters often change over the course of the story after facing a challenge or a problem, just as you were saying. Could you tell us about a way that you’ve changed over the course of your life, and what conflict or problem spurred that change?

Polacco: As a young person, you probably know this, I had great difficulty learning to read. So I didn’t think I was very smart. Part of me knew I was smart, but not book-learning smart in a conventional way. More than anything else I wanted teachers to be impressed by and love me, and I thought if they knew I was stupid, they wouldn’t. So I didn’t get help till I was in the ninth grade, and that was because George Felker [on whom Mr. Falker is based] saw what was going wrong. In every way, he changed my life and made it possible for me to trust my educators and tell them I didn’t know what they were talking about. Especially in front of other kids, you’re not going to open up and say, “Excuse me, I don’t understand what you just said.”

CCC: And that fear often continues on into our adult lives…

Polacco: It does. Much of my early life was spent trying to hide any imperfection, disability, or anything that I didn’t consider acceptable. Now I’m finding by opening up and broadcasting it, that this is where you’ll find others with you. You will have more understanding; you have people in your life that are willing to say, “Oh, okay, let me show you another way of doing this because you might get it now.” So I would say in that regard, I’ve changed dramatically. Having to face problems in a literary sense has also spilled over into my real life because hiding from things or hoping you can avoid them, which is kind of who I was earlier, doesn’t work. One thing that truly did that for me was the death of my mother [from] cancer. Boy, do you want to run from that! You do not want to face it. But you do face it and [you] realize, wait a minute, that wasn’t as horrible as I thought it would be. It’s horrible but…you realize you have strength you didn’t know you had. So now, I seek out helping people. Or I will seek out a situation that is going to be difficult because I know I can handle it. In a word, I’m braver now. I’m brave.

CCC: You talked about kids being freed up to write if they lose their fear of making a mistake. I think we all do relax and embrace life more when we’re not so focused on keeping up a facade of perfection.

Polacco: But we live in a world where that is expected of you, and you’re kind of thinking, “But that’s not really how it is. Why aren’t we living our lives in an authentic way?” Everything that I have learned that’s valuable came from stumbling and falling flat on my face, and clawing my way back up again, and thinking, “Oh, that hurt.” It’s a learning process. There’s a Russian blessing that we do in our family. Now if you were standing in front of me, I would take both of your hands and I would warn you, “We Russians spit on people we love.” If you’ve ever been to a Russian Orthodox wedding or a Greek Orthodox wedding, they spit on the bride as she’s going by. Not a hawking spit from the back of the throat. Kind of pu, pu, pu. So I would spit on you three times, holding up three fingers, and slap you soundly and say, “Remember, life at times brings pain and sorrow.” Then I would kiss you three times and say, “Remember that a kiss brings love and hope and joy, and that is what I wish for you.” That’s the Russian blessing. So in a way, I guess that’s characterized my life too.

Polacco: But we live in a world where that is expected of you, and you’re kind of thinking, “But that’s not really how it is. Why aren’t we living our lives in an authentic way?” Everything that I have learned that’s valuable came from stumbling and falling flat on my face, and clawing my way back up again, and thinking, “Oh, that hurt.” It’s a learning process. There’s a Russian blessing that we do in our family. Now if you were standing in front of me, I would take both of your hands and I would warn you, “We Russians spit on people we love.” If you’ve ever been to a Russian Orthodox wedding or a Greek Orthodox wedding, they spit on the bride as she’s going by. Not a hawking spit from the back of the throat. Kind of pu, pu, pu. So I would spit on you three times, holding up three fingers, and slap you soundly and say, “Remember, life at times brings pain and sorrow.” Then I would kiss you three times and say, “Remember that a kiss brings love and hope and joy, and that is what I wish for you.” That’s the Russian blessing. So in a way, I guess that’s characterized my life too.

CCC: There’s so much love and acceptance in your books; there’s also a lot of pain. You have some really difficult stories about racism, death, bullying, even murder. It’s remarkable to me how you’re able to leave a reader with a sense of comfort and connection, even when you address life’s pain—like in your Russian blessing.

Polacco: That’s instinct. I think you get into trouble if you think you’re never going to be in for hardship. But the secret I guess is, if there is such a thing, is to learn from it and grow from it. There’s a saying, and I don’t know who’s responsible for it, but it goes something… I’m paraphrasing, “Everything in the universe is unfolding exactly as it should, even when we do not understand why and how.” And I think that’s absolutely true.

CCC: I think that’s true, too. Life is perfect, just as it is, whether we like it or not.

Polacco: Yes. Even the pain. Even the pain.

CCC: You once said in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, “My family were extraordinary people. Quite ordinary in reality, in that they were not senators or presidents or queens or kings; but there was something so majestic and beautiful about them.”

CCC: You once said in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, “My family were extraordinary people. Quite ordinary in reality, in that they were not senators or presidents or queens or kings; but there was something so majestic and beautiful about them.”

Could you tell us something about a family member that we may not yet know from your books?

Polacco: I can relate an incident that will give you an insight into their psyche and intelligence. [It is about] my father’s mother, who is Irish. Remember, my parents were divorced. We’d spend the school year with my mom in California, the summers with my dad here in Michigan, in a village not too far away from where I live now, Williamston, just outside of Lansing. My grandma owned properties in town; the house right behind theirs was also hers and she wanted it painted. That summer my dad would come home from work every day, climb up the ladder, and paint the second floor standing on the roof of the porch. One day before he got home, I got the paint jar and the paint brush and I went over there; I was going to surprise him.

I painted like mad, and I painted not paying attention to where the window’s edges were, something a child would do. I hobbled back to the house, and I spilled paint all over the roof of the porch. I came back to the house, expecting my dad to be just thrilled. My father stopped by that house, saw what I had done, and came storming in. Shaking and white with fury, he grabbed me, sat me on the kitchen counter. Sat me down pretty hard. My grandmother whispered something in my father’s ear and his face softened and his eyes filled with tears. He said, “Oh Patricia, you did such a beautiful job. Thank you.” I found out years later what my grandmother whispered in his ear was this: “William, what you say and do to this child next, she’s going to remember as long as she lives.”

That’s how they were. They were wise, gentle. Some of them were educators. They were bright; they were smart. They were voracious readers, every one of them. We always had a library full of books. Just being around them made my heart sing, and I think that was accomplished by the firetalking. That’s why it’s so important to sit and tell stories to your kids. We would sit at their knees, always wanting to know how was it in the “olden days” I called it. My grandson just pulled that one on me. “Granny, what was it like in the olden days?” “What do you mean, the olden days?” I still feel 18. I don’t feel as old as I am. But they’re interested in hearing it.

I’ve had young couples come over with small kids, eight or nine years old, and we’ll have dinner together. The kids want to rush into the great room and watch TV, and I let ’em go. But then we start reminiscing and talking about how things were. One by one, those kids come back to the table and they sit down. They get a dreamy look on their faces, and they’re so eager to hear the stories of our neighborhood, some of the kinds of things that we did.

We’re robbing the children of the ability to hear these stories. Technology is also doing a number there because we have so many bells and whistles and toys that they pay attention to, instead of hearing rich language spoken by a human voice, sitting on their lap, or sitting near them, and just watching their faces, and hearing their families. Our dinner table always groaned with food. Then after dinner came the raucous laughter and sometimes horrifying arguments, because they were very political and they wanted to talk about how they thought the world should be run. They never necessarily have the same ideas, and it would get pretty rousing. But it was…

CCC: Life.

Polacco: Yeah, it’s fighting, and lively, and full, and rich. We never had a penny, but by golly, they shared their hearts.

CCC: Something you said there was telling: you said when you have these friends over for dinner and then after, the kids want to go to the great room and watch TV and you said, “We let them.” I think that is important, and it’s also kind of a tricky balancing act these days; it used to be just television, but that is the least of it now with the laptops, and the phones, and the games. It is difficult to preserve the family space.

Polacco: Yes, but don’t try to legislate it, that’s my point. Let ’em go in there, and do it. When they hear the laughter, or hear fabulous conversation, one by one, I promise you, they will be back in that room. Because they want to hear it. They want to hear what you think.

When I’m on the road, I eat in a lot of restaurants alone. I put a book in front of me so people think I’m reading, but I’m not. I’m listening to everything they’re saying. I’ll see a family of five or six come in, sit at a table, all of them are on their devices. They’re not even talking to each other. And I want to go over there and say, “Sweetie, tomorrow, this child is going to be 45 years old.” It’s going to happen with greased lightning. Please talk to them. Hear what’s in their hearts. Share what you’re afraid of; they need to know you’re vulnerable.

My mom, every Saturday morning, when I was a teenager, we used to roll up balls of ground beef, put them in the broiler, put a little bit of garlic sauce on it, and make stone ground toast. And then she and I would sit at the kitchen table and just talk. I loved that. Here’s the vacuum cleaner sitting there, because I’m supposed to be vacuuming. And she’d say, “Don’t worry about it.” And we’d talk about everything.

CCC: I’d like to follow up with you on technology…

Polacco: I think it’s a wonder; it’s a wonderful thing. It’s given us the opportunity to literally reach out and know what the entire world is doing. The exception is it’s robbing our kids of the incentive to invent a game and play outside.

CCC: What do you think about the use of technology in the classroom, and how do you use it in your own life? I know you are on Facebook, and you do reach a lot of people that way.

Polacco: It’s a wonderful thing for children to have a window on the world, to have access to current events. Some children, let’s say their handwriting isn’t great, but they can type like mad on a word processor. Well to me, that’s also encouraging them to write. Like I say, the exception I take to it is when the technology overshadows what I consider normal behavior of a child. Get outdoors, breathe some fresh air, invent some games.Here’s what I say to children: “You have a voice inside of you where all art, literature, and beauty comes from. The problem is, when you bury your face in a device, you can’t hear the voice anymore.” And their eyes get big. I say, “Turn it off once in a while. Just turn it off! And then get out there and see what you’re going to see, and smell what you’re going to smell, and feel what you’re going to feel. Roll down a hill, and get yourself so dizzy you vomit.” That’s life.

CCC: Your characters vary greatly—age, gender, race, religion, ability—but they all have a common thread. They usually reveal our shared humanity in some way. I’m thinking here about young Pink’s kindness, Eula Mae Walker’s love and empathy, Babushka Baba Yaga’s bravery, and so on. How have readers responded to specific characters over the years? Have there been any reactions that surprised you?

CCC: Your characters vary greatly—age, gender, race, religion, ability—but they all have a common thread. They usually reveal our shared humanity in some way. I’m thinking here about young Pink’s kindness, Eula Mae Walker’s love and empathy, Babushka Baba Yaga’s bravery, and so on. How have readers responded to specific characters over the years? Have there been any reactions that surprised you?

Polacco: They usually identify with a character that’s having the same struggle they are. For instance… my story about the two women, my two moms.

CCC: In Our Mothers’ House, right?

Polacco: Yes, In Our Mothers’ House.

That story came from being in a fourth-grade class, [and] the kids were asked to stand up and read the essays they had written about their family. The teacher left the room and there was an aide still in there. One little girl stood up and started to read “My family…”, and the aide said, “No, no. You sit down. You don’t come from a real family.”

That is the family that ended up in the book. Now oddly enough, my own daughter is gay, so she was one of the mothers and her partner was the other. In that regard, they weren’t fictional. But this little girl came from a family very much like what was depicted in that book. I was absolutely enraged by the time I got back to my hotel, not because of my daughter’s position, but any child’s position, for god’s sake. And I wrote the story immediately, and put it together. That one went faster than anything I’ve ever done.

CCC: I thought that was a really beautiful book, and again, you don’t throw blame or condemnation around. You’re very empathetic and understanding. But the misguidedness of these beliefs is made clear.

Polacco: I think that [misguidedness] is the enemy. It isn’t so much people are evil; I think some of the things they think are based on real misinformation and they’re acting on it. I think most people, if you give them a chance and they’re allowed to see the truth, they come around and they say, “Oh. Yeah, we are on this small blue dot, aren’t we? Better pull together.”

A lot of children have responded to Thank You, Mr. Falker and The Junkyard Wonders. We were called the “junkyard,” because I had just learned to read, and I was put in a special class, and they called it the junkyard. This is where I knew Thom from. Anyway kids will say, “Oh, my gosh! When I read this book, that’s me!” One of the little characters in Junkyard, Gibbie, has Tourette’s syndrome. I had a child come up to me recently who had Tourette’s and said, “ Nobody’s ever written about us.” I don’t specifically write about them, but they’re a character in the book. Because isn’t that really what life is like? It’s not necessarily centered on them, but there they are. So yeah, I guess in that regard, I will have people say the story had specific meaning to them.

CCC: You’ve documented the profound effect certain teachers had on your life through characters like Mr. Falker and Ms. Keller. In an NPR interview, you said, “Teachers are the last standing heroes we have in our country, and I don’t say that lightly.” What inspired that comment?

CCC: You’ve documented the profound effect certain teachers had on your life through characters like Mr. Falker and Ms. Keller. In an NPR interview, you said, “Teachers are the last standing heroes we have in our country, and I don’t say that lightly.” What inspired that comment?

Polacco: Well, I believe they are heroes. Why would anybody pick a profession that they have to go to school probably six years for, [and] where they’re going to be underpaid, overworked, and then disrespected for the pleasure of doing it? And I think the thing that really rang home for me is Sandy Hook. I used to visit Sandy Hook [Elementary] School a great deal. I was their artist-in-residence and visiting author. I was there that day; I knew all of those people. I flew out hours before it happened. The principal was a very good friend. And when I landed and came to my house, I watched it on TV just like the rest of you did. That’s when I collapsed and went to the hospital, and had open-heart surgery three days later.

I’ve always thought teachers were heroic because of the profound influence they have on the lives of our children. They’re never thanked; they’re always blamed if anything goes wrong. They’re never respected, in my opinion, for what they do—well not wholly, not enough.

I used to go to Russia often, and I remember standing in long food lines, and I mean long food lines, and a woman would come up with a string bag and everybody would pull back and let her go in front. I asked one of the women I was with, “Is she a politician’s wife? Is she someone special?” They said, “Oh my god, yes. She’s a teacher.” And I thought, “If we could only learn that one here!”

I do believe they’re heroes, notwithstanding Sandy Hook, even before that happened. When you think about it, nine teachers were shot that day. Six of them didn’t make it. Three did, if you want to call it that. They walked into bullets to save children that were not theirs, and orphaned their own. Now that takes somebody [who] is very brave and very dedicated. I see wonderful teaching happening out there. By the same token, I think they are hobbled by all of the… What would you call them? The latest flavor of the month. No Child Left Behind was a horror, and some of the broad-brush horrible testing that they’re doing to children now. You can’t tell me a second grader doesn’t know their life depends on passing that test. Yes, they do. Yes, they do.

CCC: They know. The teachers know too.

Polacco: It’s just so destructive. I think teachers should be trusted. I think they know because they lead with their hearts, most of them do. You might have a bad apple here and there, but not that often, not really. I ask you, who would choose this profession if they didn’t have some passion for it? Unless they are very dedicated people who really want to be around young people and mold their minds. I think that takes a very exceptional person.

CCC: We care a lot about the sense of community in the classroom. Over and over again in your stories, you remind the reader that no matter how hard things are, they have a place in the world, that they belong in it, and that they’re part of the human family. How do you think teachers can nurture that sense of belonging in the classroom?

Polacco: Well, the classroom itself is usually a microcosm of the world.

Give kids a sense of space and a sense that their classroom is preparing them for the world. Encourage them to do their own governing; encourage them to come up with ideas and interact with each other, to sit down in groups and figure out what they’re going to do to make their problems better. That gives them a sense of community.

Something that I think is very sad is that we cannot celebrate any holidays in public schools. Every religion you can imagine is probably happening in any given school. Why can’t we celebrate Christmas, celebrate Hanukkah, celebrate Ramadan, celebrate Shinto, celebrate everything there is? Because to me, this gives the child a bird’s eye view of the real world—Allah, Buddha, Jesus, God, the Upanishads, etc. They all have different names, but you know what, they’re from the same entity. We’re the same.

CCC: Instead of eliminating spirituality or religion, why not embrace every single one?

Polacco: I’m glad you brought that word up because to me, that’s what we have to get in touch with—the spirit among us. Our spirits strive for exactly the same thing.

Humanity matters and the spirit matters. All other things really fall by the wayside.

Patricia Polacco was born in Lansing MI in July of 1944 to parents of Russian and Ukrainian descent on one side and Irish on the other. She earned an M.F.A and a Ph.D. in art history, specializing in Russian and Greek painting and iconographic history. Patricia has authored and illustrated over 100 books and stories in her 30-year writing career; she draws upon her rich heritage of mixed cultures for her inspiration. She visits elementary schools all over the United States and Canada sharing her message of tolerance, acceptance, diversity, love, and respect to children of all ages. The mother of two adult children and two grandchildren, Patricia loves being with family whenever she is not traveling. She lives in South Central Michigan on her farm, Meteor Ridge, with her many cats, squirrels, horses, dogs, and goats. Her latest book is Remembering Vera about the beloved pet and mascot of the San Francisco Coast Guard, based on Coast Guard Island in Alameda, CA.