“I am attracted to the idea of seeding the imagination by leaving a little something untold.”

Children’s books are the cornerstone of many of Center for the Collaborative Classroom‘s (CCC) programs; in a way, the authors are our behind-the-scenes collaborators. We want teachers, administrators, students, and parents to be able to learn more about these wonderful authors. We are happy to present the third in a series of author interviews, with Chris Van Allsburg. Five of his books are used in our programs: Just a Dream, Probutiti!, The Sweetest Fig, and The Wreck of the Zephyr in Being a Writer; The Wretched Stone in Making Meaning.

CCC: You’ve said the kind of story a writer ends up telling is a result of the kind of person that the writer is, and you also caution that thinking about your audience is poisonous to the art process. Children, particularly adolescents, tend to be especially concerned with audience. How do you think educators can help students be true to themselves and to their imaginations?

Chris Van Allsburg: I understand the problem you’re describing. I have for many years received in the mail stories that kids have been motivated to write by viewing the pictures and captions that appear in The Mysteries of Harris Burdick. I noticed that when I got stories from younger kids-even though they sometimes struggled with language and their grammar wasn’t particularly good-they seemed to be pretty imaginative. More so than the stories that I received from kids who were older. It seemed that as children grew older, their ability to communicate with language improved, but their imaginations seemed to diminish.My feeling is that what happens is this: overexposure to other media can contaminate their own imaginative process. By the time they get to be 13, 14, they have seen so many films, played so many videogames, watched so much television, that initially when they’re called upon to express their own ideas, they just download things that have already been uploaded through their eyeballs. This is what initially passes for self-expression: the emulation of something that they’ve already been exposed to. How do you deal with it? I agree that adolescents that anticipate sharing what they’ve written might be, while they’re writing, concerned about the reaction of their peer group to what they’re working on (and could end up sharing). How do you meet that challenge? Also, how do you get a young writer to somehow put aside all the other stories whether they’re literature, cinema or television-how do they put those in a place where they’re not constantly shaping the writer’s own thoughts. And, how do they get in a place where they can write without anticipating or worrying about their classmates’ reaction?The second problem I think is in some ways easier to address than the first. That is the concern about the reception of your work while you’re doing it. I think it’s not that difficult to find a state of mind where you can pretend that no one ever will see the thing that you’re writing, where you can simply persuade yourself that, “There’s no one standing over my shoulder, there’s nothing being recorded here. It’s me on my computer screen, or me with a pencil and paper in front of me,” and it’s actually empowering to know that “I can do this in complete solitude, I can write the craziest, wildest, most embarrassing thing. If upon completion that seems to be the case, I can erase it, or I can rumple it up in a little ball and throw it in the wastebasket.”

How do you deal with it? I agree that adolescents that anticipate sharing what they’ve written might be, while they’re writing, concerned about the reaction of their peer group to what they’re working on (and could end up sharing). How do you meet that challenge? Also, how do you get a young writer to somehow put aside all the other stories whether they’re literature, cinema or television-how do they put those in a place where they’re not constantly shaping the writer’s own thoughts. And, how do they get in a place where they can write without anticipating or worrying about their classmates’ reaction?The second problem I think is in some ways easier to address than the first. That is the concern about the reception of your work while you’re doing it. I think it’s not that difficult to find a state of mind where you can pretend that no one ever will see the thing that you’re writing, where you can simply persuade yourself that, “There’s no one standing over my shoulder, there’s nothing being recorded here. It’s me on my computer screen, or me with a pencil and paper in front of me,” and it’s actually empowering to know that “I can do this in complete solitude, I can write the craziest, wildest, most embarrassing thing. If upon completion that seems to be the case, I can erase it, or I can rumple it up in a little ball and throw it in the wastebasket.”

CCC: Give yourself the opportunity to express yourself, knowing that you can bail out if you feel you need to.

Chris Van Allsburg: Right. There’s a complete freedom in the writing process if you understand that the thing you’re sitting down to do now is not something that you are necessarily going to share with anyone. It’s like a diary entry-even though it’s a story, even though it’s something you made up, or even though it may be an essay you’re writing in response to a school assignment. The solitary act of turning your thoughts into words has little risk involved when you’re sitting down doing it for the first time. If you’re unsatisfied with what you’ve just done, you can decide not to share it. If it’s a homework assignment, you’re going to have to give it another shot. The possibility of private revision should be liberating.It’s probably destructive to have kids sit in a classroom and teachers give them an assignment and say, “In an hour, I’m going to ask a few of you to stand up and share with the class what you’ve written.” I’m sure that would not only be inhibiting, but it would definitely cramp a person’s style-that the thing they’re doing is not private. What’s best about writing-and what I was getting at when I said that writing finally is the result of the kind of person, or the personality that’s doing the writing-it’s really only authentic if it’s genuinely personal, and is an expression of ideas, thoughts and emotions that you have connected with and that aren’t mediated by your concerns about the reactions of others to it.

CCC: That’s a good point about not requiring the reading in class. You can ask for volunteers…

Chris Van Allsburg: Right, that would make sense. At some point if the teacher felt that the whole undertaking was going to be catalyzed by students actually getting up and reading, I would guess that the challenge would be to create a classroom setting that’s nonjudgmental.

CCC: That’s a key feature of CCC programs: we try to create an environment where kids feel safe. They’ve been taught how to listen, to respond in a way that’s not critical, but is constructive and curious.

Chris Van Allsburg: Right. We addressed slightly the question of how challenging it might be to write and somehow block out the idea that at some point it will need to be shared. We still haven’t addressed the first problem, which is: When young people have acquired enough language skill and they’re in a position where they can actually start to use those skills to try to become a writer, to put their thoughts down on paper-or on a screen-when they’re ready to do that, maybe eager to do it or cautiously exploring it, how do they purge the process of all the media that they’ve experienced up to that point and try to produce something like an authentic or personal voice in the work. I think that’s in some ways the more difficult problem. Once you start writing, part of the process-even when it’s undertaken with a spirit of personal revelation-it’s always going to be shaped by events in your life. That event or experience, that thing that happened to you uniquely can be the inspiration for writing in the first place. But the fact is that the thousands of hours that you watch TV also amounts to an event in your life. And they are all part of the mix that is the writer.I would say that the best defense against letting your work be too strongly influenced by the media you’ve consumed is to jump in, start writing and be critical. Look at what you’ve written and ask yourself: Does this remind me of something? Is it really my voice? Or, am I simply recycling what I watched or read earlier in the year, or earlier in my life? Distance yourself from it in some way. I suppose that distancing is just a matter of being self critical and being able to look at the thing that you put down and being able to identify it as having your own creative DNA in it. Focus on the feelings you’ve had as a result of events in your own life, and not the feelings you had when you were exposed to someone else’s story on film.

CCC: A teacher could take this as an opportunity to talk to the kids about being more conscious of storylines and images and ideas that are rolling around in their minds based on television, videogames, or movies that they’ve seen, to be able to recognize them, and when they sit down to write, put them aside.

“No child gets to the age of 10 or 11 without having experiences in their own lives that are more profound than the drama that they’ve seen on a video screen.”

Chris Van Allsburg: One thing that should help them not simply put them aside, but render them less powerful is the fact that no child gets to the age of 10 or 11 without having experiences in their own lives that are more profound than the drama that they’ve seen on a video screen. I think if they can use their, maybe not their imaginative powers, but simply the powers of memory to place themselves back in events that happened in their own lives, I think those have the potential to awaken a personal voice, because you’re describing something that’s uniquely yours-an event in your life, a story that you’re imagining-but it’s built on feelings that you’ve actually had that were triggered by some real family drama or real family crisis. I don’t want to get too “heavy” about it, but it’s sort of a therapeutic sense of…if you get in touch with the feelings that you associate with the authentic and important events that have happened in your life, those will push aside the “sham” emotions that are part of our response to watching media. So basically, what I’m arguing for is a way to encourage students as much as they can to draw on things that have happened in their own life because that has a power that will push aside the ersatz stimulation that they’ve had in their digital world.

CCC: And, should they end up feeling comfortable enough to share those stories with others, the response might be so gratifying that it’s reinforcing.

Chris Van Allsburg: Reinforcing them as young writers, but also reinforcing the idea that there’s something really positive about self-reflection that celebrates your individuality and trumps your identity as just a victim of your culture.

CCC: You are probably pretty capable of mining your personal experiences, but I do wonder how difficult it might be for you to keep this massive audience at bay when you’re working?

Chris Van Allsburg: The first book that I wrote I wrote with an absolute sense of isolation and a conviction that the thing that I was producing would probably find a very tiny audience and that it would be the last thing I ever wrote. The result of having a book published would be that I find myself in a position, after all the returns had come back to the publisher, of being able to buy my books at a sharply remaindered discount, and have Christmas gifts for the rest of my life to give to friends and associates. It wasn’t really so much a matter that I lacked confidence, I just didn’t believe in the commercial prospects of the thing that I was doing-because I knew that it was so different from the books that I’d seen that were popular at the time. It wasn’t that I didn’t give credit to the young audience that I presumed would be introduced to my work, but on the other hand…the illustrations I was making were black and white charcoal drawings and, based on my exposure to children’s literature at the time, I couldn’t see that my book fit into the genre. Once I turned it in, I went back into my sculpture studio and sort of forgot about it. So that first book, in terms of being unaware-or keeping this notion of a breathless audience at bay-was not difficult at all, because I knew there was not one there. As I said before, it’s really liberating to know that the thing that you’re doing, you’re doing in solitude. It gets more difficult when it becomes a commercial endeavor.The point I’m making is that once you’re involved in something like picture-book making, you’re no longer-even though you could do it in isolation, and can pretend that maybe no one will buy it or see it, it is still the fact that in some part of your mind, you have to acknowledge you are now making something that is essentially a public art form. It’s not private like making a piece of sculpture, or making a painting, which if you’re dissatisfied with, you can choose not to send to the gallery and no one will see it.So with the second book, because of the success of the first, my awareness of an audience was greatly heightened. Now there may be some expectations, certainly, at least, on the part of my publisher. But in a broader sense, the people who received the first book favorably might be curious about the second one. I didn’t delude myself into thinking that there was a large group of people who were not getting to sleep at night because they couldn’t wait to see the next effort.I still was able to function inside my small studio with the belief that this was once again a solitary act. I was able to compartmentalize the idea that it would be seen by others and I felt strongly about it because one of the things I’ve always valued very highly in art is authenticity and originality. As soon as the creation of art acknowledges an audience and the artist allows for the notion of audience, turning them into an approval seeking creator, then it’s no longer going to be authentic and original. So I had a heightened vigilance. I just climbed back into my imagination and made a story that satisfied me and decided to draw it again in black and white because that was frankly all I knew how to work with then.It was funny-I was praised as original because my first books presented “a very creative and inventive kind of illustration.” Some of the reviews had said: Van Allsburg has chosen to do these works monochromatically and they have a kind of mystifying surrealism that’s so much more appropriate for the text. So they were very complimentary, but the reality is that because I studied sculpture exclusively during my years in school, I really didn’t know how to use anything else except a pencil. So I was being praised for having made a choice, when in fact, I was being praised for a limitation. At the same time, I knew that because the first book was the first book I had drawn, I believed that I could do better if I tried a second one, and that’s always a motivation to an artist: the idea of how work will evolve if one keeps on refining their skills. So I did learn a little bit more about drawing, and I became a better figure drawer and I became a better manipulator of the medium in the second book.What excited me while I was doing it was not the idea of: Oh, gosh, wait till they see this one. It was: Oh, gosh, this is so much more satisfying because I feel like I know more now. My excitement in the work was the result of learning something each day that I sat down to draw. I was learning how to manipulate the materials and create effects that I didn’t know how to create before. I think that that engagement with the materials was a way for me to disengage with this idea about an expectant audience.

Chris Van Allsburg: The first book that I wrote I wrote with an absolute sense of isolation and a conviction that the thing that I was producing would probably find a very tiny audience and that it would be the last thing I ever wrote. The result of having a book published would be that I find myself in a position, after all the returns had come back to the publisher, of being able to buy my books at a sharply remaindered discount, and have Christmas gifts for the rest of my life to give to friends and associates. It wasn’t really so much a matter that I lacked confidence, I just didn’t believe in the commercial prospects of the thing that I was doing-because I knew that it was so different from the books that I’d seen that were popular at the time. It wasn’t that I didn’t give credit to the young audience that I presumed would be introduced to my work, but on the other hand…the illustrations I was making were black and white charcoal drawings and, based on my exposure to children’s literature at the time, I couldn’t see that my book fit into the genre. Once I turned it in, I went back into my sculpture studio and sort of forgot about it. So that first book, in terms of being unaware-or keeping this notion of a breathless audience at bay-was not difficult at all, because I knew there was not one there. As I said before, it’s really liberating to know that the thing that you’re doing, you’re doing in solitude. It gets more difficult when it becomes a commercial endeavor.The point I’m making is that once you’re involved in something like picture-book making, you’re no longer-even though you could do it in isolation, and can pretend that maybe no one will buy it or see it, it is still the fact that in some part of your mind, you have to acknowledge you are now making something that is essentially a public art form. It’s not private like making a piece of sculpture, or making a painting, which if you’re dissatisfied with, you can choose not to send to the gallery and no one will see it.So with the second book, because of the success of the first, my awareness of an audience was greatly heightened. Now there may be some expectations, certainly, at least, on the part of my publisher. But in a broader sense, the people who received the first book favorably might be curious about the second one. I didn’t delude myself into thinking that there was a large group of people who were not getting to sleep at night because they couldn’t wait to see the next effort.I still was able to function inside my small studio with the belief that this was once again a solitary act. I was able to compartmentalize the idea that it would be seen by others and I felt strongly about it because one of the things I’ve always valued very highly in art is authenticity and originality. As soon as the creation of art acknowledges an audience and the artist allows for the notion of audience, turning them into an approval seeking creator, then it’s no longer going to be authentic and original. So I had a heightened vigilance. I just climbed back into my imagination and made a story that satisfied me and decided to draw it again in black and white because that was frankly all I knew how to work with then.It was funny-I was praised as original because my first books presented “a very creative and inventive kind of illustration.” Some of the reviews had said: Van Allsburg has chosen to do these works monochromatically and they have a kind of mystifying surrealism that’s so much more appropriate for the text. So they were very complimentary, but the reality is that because I studied sculpture exclusively during my years in school, I really didn’t know how to use anything else except a pencil. So I was being praised for having made a choice, when in fact, I was being praised for a limitation. At the same time, I knew that because the first book was the first book I had drawn, I believed that I could do better if I tried a second one, and that’s always a motivation to an artist: the idea of how work will evolve if one keeps on refining their skills. So I did learn a little bit more about drawing, and I became a better figure drawer and I became a better manipulator of the medium in the second book.What excited me while I was doing it was not the idea of: Oh, gosh, wait till they see this one. It was: Oh, gosh, this is so much more satisfying because I feel like I know more now. My excitement in the work was the result of learning something each day that I sat down to draw. I was learning how to manipulate the materials and create effects that I didn’t know how to create before. I think that that engagement with the materials was a way for me to disengage with this idea about an expectant audience.

CCC: I remember you said you came up a little short because your skills couldn’t match your imagination yet.

Chris Van Allsburg: And that continues to be true.

“It may be that my imagination is the only place where the book will be perfect.”

CCC: It’s great that that feeling would continue to drive your art, and drive away the sense of audience expectation.

Chris Van Allsburg: Yes, because this idealized vision of the yet-to-be created book is powerful motivation. I can envision what I think a book will be like, the atmosphere the book will create between the cardboard covers, and I’ve never actually been able to measure up to the ideal that exists in my imagination before I sit down to make it. Many months later, the book is finally created, it’s printed, it’s bound. It has never been the case that I got that first bound book back from the printer and opened it up and said, “Gosh, I really nailed it.” That’s never happened. Because of that, it makes me think: Maybe next time. Whenever people ask me, “Gee, you’ve done a number of books now. What’s your favorite?” I will always tell them, “Well, my favorite’s the one I’m going to do next because that will be better than the ones I’ve done so far.” It is important for an artist to feel that way.

CCC: Do you feel that you’ve progressed with every book?

Chris Van Allsburg: Nope. Some books I think I’ve gotten a little bit closer, and perhaps you’d think it will be a natural forward progression, but The Queen of the Falls is my seventeenth book and I would not say that each of the previous has marked another step forward in my ambition to create the book that as closely as possible resembles the thing I imagine. There have been some books that I think have been a little bit closer that are not my most recent book, but they’re all off the mark-and in ways that are not easy for me to describe. So it may be that my imagination is the only place where the book will be perfect. When it becomes a physical thing, I’ll have to accept the ways that it doesn’t measure up.

Chris Van Allsburg: Nope. Some books I think I’ve gotten a little bit closer, and perhaps you’d think it will be a natural forward progression, but The Queen of the Falls is my seventeenth book and I would not say that each of the previous has marked another step forward in my ambition to create the book that as closely as possible resembles the thing I imagine. There have been some books that I think have been a little bit closer that are not my most recent book, but they’re all off the mark-and in ways that are not easy for me to describe. So it may be that my imagination is the only place where the book will be perfect. When it becomes a physical thing, I’ll have to accept the ways that it doesn’t measure up.

CCC: Which reader responses to your characters or books have surprised you the most?

Chris Van Allsburg: I guess it would go back to the experience I had with the first book. The response that surprised me the most was that I’d made something that found an audience that was much larger than I expected, that it would get a Caldecott Honor Medal, that it would quickly go back into a second printing and that it’s now-32 years later-still in print. Remarkably, all my books are still in print.I did an alphabet book that’s basically 26 acts of somewhat sadistic torment of letters and when I shared this idea with my editor, he said, “Listen, Chris. We’re happy to publish anything that you want to do because we have faith in your work, and we believe your work will find an audience, but that’s kind of strange.”And I said, “I think it’ll be good because all the alphabet books out there-they’re all about A is for Apple, B is for Banana, and I think that’s got to be kind of boring for kids.” I know that alphabet books are used primarily by younger kids but it occurred to me that if I was a young kid it would be interesting to have an alphabet book that was about verbs, about things that happened. Not about things that just sat on a kitchen counter. So I did that and it’s still in print, and it’s a fairly popular alphabet book.I guess I have to say in a kind of sweeping way the thing that most surprises me about people’s response to books that I have done-I don’t want to sound like Sally Fields here-but that they like them. Because things that have commercial popularity in the marketplace are not ordinarily idiosyncratic. When I look at my body of work, I feel it’s a little unconventional, not because I’m striving for that, but because that’s the way it ends up coming out of my hands. And yet, there’s an audience that’s embraced it. That’s not only a surprise to me, but it’s an enormous satisfaction.

“When I look at my body of work, I feel it’s a little unconventional…. And yet, there’s an audience that’s embraced it. That’s not only a surprise to me, but it’s an enormous satisfaction.”

CCC: You are surprised that they followed you and your imagination wherever you’ve gone?

Chris Van Allsburg: Yes, I get fan mail-not just from the U.S., but from Asia as well, and for books that I thought were maybe a little bit of a challenge. For instance, The Stranger, which is a series of sort of riddles; if you answer them correctly, you can actually identify the stranger by the end of the book. In my mind he was always Jack Frost. But I get letters from kids down south where the mythological character Jack Frost doesn’t exist. For me he was this fleet-footed character who moved like the wind through the forest and turned all the leaves from green to red and gold. This was the story I was writing, and it didn’t occur to me that the character in question only exists in northeastern mythology-northeastern American mythology.And yet, I get letters from kids from the south that are completely mystified and baffled by who the stranger might be and they propose all sorts of different identities. I also get mail from kids in South Korea-actually, not so much from the kids, but from their teachers. I can tell from my royalty statements that my book sells fairly well in South Korea and I’m just wondering: What do they make of this “Stranger”? It has to be a complete mystery to them. It’s a satisfaction not simply because it’s a response to my work, but it’s such a pleasure to know that people can engage with books that are mysteries to them and still find meaning and pleasure in them. They will pick them up absent the happy resolution they’re used to-or any resolution at all. That says something to me about the human intellect and reading appetite that’s encouraging, that I find positive.

CCC: Your stories tend to exist simultaneously in the real world in part through meticulous artwork and the fantastical. What advice can you offer young writers about creating stories that are imaginative and accessible at the same time? One of the things I was thinking about with this question is that sometimes-especially younger-kids can get so carried away that you can kind of get lost in the storyline and you lose your reader completely. You don’t do that.

Chris Van Allsburg: My approach to fantasy has always been that there’s only going to be one fantastic notion, or one supernatural feature in the story. Around that single supernatural feature, everything else has to follow the rules that we’re familiar with. So, the way I manage it is that I do try to create a recognizable world and as you pointed out, that probably is one of the reasons that I draw in a fairly representational style, because I’m depending on the artwork to create that recognizable reality. But then inside that pictorial reality, I try to introduce this strange event, and I try to maintain a faithfulness to reality that we are accustomed to in every other way. So I give myself one wild card, but every other card that I play has to be a real one.

“My approach to fantasy has always been that…I give myself one wild card, but every other card that I play has to be a real one.”

What happens in some fantasy writing is that the author does not impose enough rules on themselves so that the magic and the fantasy start to feel arbitrary, like there’s no structure or restraint, so if anything can happen in your story-because that’s the fantasy that you’ve created-then, nothing that happens really feels fantastic because anything could happen. If you create enough reality around the fantastic, then the fantastic still seems, by comparison to the mundanity or the quotidian that surrounds it, fantastic. I always say you get one of these cards and you can play it, but once played, everything else must follow the logic of human behavior and the real world. That’s sort of been my story model.

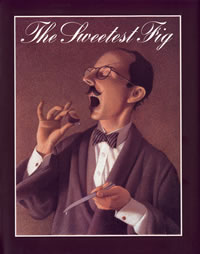

CCC: The characters in your book vary tremendously, but each one’s personality feels authentic. Monsieur Bibot in The Sweetest Fig, and Calvin in Probuditi! are just two examples. How do they develop in your mind? You have used individuals in your life as models for the drawings of the characters in your stories. Where do you find models or inspiration for a character’s temperament?

Chris Van Allsburg: I think in some ways that even unlikable characters are to a degree the result of access to parts of my own personality. They’re all a little autobiographical-and I’m not trying to glorify it or romanticize it so much, but when you’re creating a character, you get your understanding of them, I think, in the same way an actor does. You have to try to feel a little of that emotion in yourself. I mean, I own a dog and I fancy that my dog loves me and I love my dog. I don’t drag my dog around on a leash, but there have been times when the dog’s just sniffed for a little too long and I can imagine the impatience that can induce someone to, whether the dog wants to walk or not, just keep dragging it. So a small part of it can be autobiographical. Actually, with respect to The Sweetest Fig, I was in Paris, and I saw a man dressed in a very fancy suit. Many people in Paris have tiny dogs. I saw this man pull his small white dog away from a bush that the dog was deeply engaged with in an olfactory curiosity. I believe that story material like this is everywhere. I’m not sure if we were in view of the Eiffel Tower when I saw this man dragging the little dog on the leash. But that image stayed with me. When I got back from Paris I was wondering if there was a story there. That became the motivation for The Sweetest Fig, but I think the specific details-the embittered quality that the dentist reveals, the lack of generosity. Once again, I don’t associate with any of those things, but I can sort of imagine the disappointment of having worked at something and then when someone has promised a recompense and it’s not there, getting peevish about it. But in other ways, somebody like Bibot is an archetype, so here I will contradict myself with respect to avoiding the use of material that is not part of your own life.Many archetypes (we don’t run into them that often in our own lives, but we’ve been exposed to them through the media, through our reading, through our film watching-in my case for decades) are subjects that exist in our imaginations. So Bibot is an archetype of a sort, and, in that sense, a compilation of attitudes that I sense exist in moderate ways in myself. In Probuditi!, Calvin was actually more inspired by the torment I saw in the way my children treated each other when they were quite young and probably some of the conflicts I had with my own sister. I was the younger sibling, I don’t remember being teased and exploited so much by her, but I’ve seen it in real life frequently. The simple dynamic that exists between siblings and how birth order gives the upper hand to the older child who always has an advantage because of size and strength, because they’re a little older, and know a little bit more.

So a small part of it can be autobiographical. Actually, with respect to The Sweetest Fig, I was in Paris, and I saw a man dressed in a very fancy suit. Many people in Paris have tiny dogs. I saw this man pull his small white dog away from a bush that the dog was deeply engaged with in an olfactory curiosity. I believe that story material like this is everywhere. I’m not sure if we were in view of the Eiffel Tower when I saw this man dragging the little dog on the leash. But that image stayed with me. When I got back from Paris I was wondering if there was a story there. That became the motivation for The Sweetest Fig, but I think the specific details-the embittered quality that the dentist reveals, the lack of generosity. Once again, I don’t associate with any of those things, but I can sort of imagine the disappointment of having worked at something and then when someone has promised a recompense and it’s not there, getting peevish about it. But in other ways, somebody like Bibot is an archetype, so here I will contradict myself with respect to avoiding the use of material that is not part of your own life.Many archetypes (we don’t run into them that often in our own lives, but we’ve been exposed to them through the media, through our reading, through our film watching-in my case for decades) are subjects that exist in our imaginations. So Bibot is an archetype of a sort, and, in that sense, a compilation of attitudes that I sense exist in moderate ways in myself. In Probuditi!, Calvin was actually more inspired by the torment I saw in the way my children treated each other when they were quite young and probably some of the conflicts I had with my own sister. I was the younger sibling, I don’t remember being teased and exploited so much by her, but I’ve seen it in real life frequently. The simple dynamic that exists between siblings and how birth order gives the upper hand to the older child who always has an advantage because of size and strength, because they’re a little older, and know a little bit more. I love the old folk tales where cleverness triumphs over strength, so I had this idea of a sibling rivalry or conflict that fell into that genre of story wherein the guile and wit of the weaker party is able to triumph over the strength of the larger party. In cases like Probuditi! Calvin, the self-satisfied older sibling was, once again, a kind of an archetype that I’ve seen many times in different families, read about in many stories, and saw to a lesser degree in my own children.I would say then, in a general sense, my characters are composites of the archetypes that I’ve been exposed to in my life. Some archetypes can be compelling characters in a story. The idea of character development and delineation or presentation of a character who is memorable and a somewhat familiar type, can bring a story to life. If that was something that was a result of a young writer having read Dickens all their life, I don’t think anyone would criticize them for having been too heavily influenced by their culture. At the beginning of the conversation, I was criticizing how the effect of having ingested too much culture could prevent you from finding your own voice, but right now, I guess I’m arguing for the tactic that reading certain authors can be a real inspiration in the use of certain narrative devices, of certain character archetypes. Certainly, cultural influence can work in many ways.

I love the old folk tales where cleverness triumphs over strength, so I had this idea of a sibling rivalry or conflict that fell into that genre of story wherein the guile and wit of the weaker party is able to triumph over the strength of the larger party. In cases like Probuditi! Calvin, the self-satisfied older sibling was, once again, a kind of an archetype that I’ve seen many times in different families, read about in many stories, and saw to a lesser degree in my own children.I would say then, in a general sense, my characters are composites of the archetypes that I’ve been exposed to in my life. Some archetypes can be compelling characters in a story. The idea of character development and delineation or presentation of a character who is memorable and a somewhat familiar type, can bring a story to life. If that was something that was a result of a young writer having read Dickens all their life, I don’t think anyone would criticize them for having been too heavily influenced by their culture. At the beginning of the conversation, I was criticizing how the effect of having ingested too much culture could prevent you from finding your own voice, but right now, I guess I’m arguing for the tactic that reading certain authors can be a real inspiration in the use of certain narrative devices, of certain character archetypes. Certainly, cultural influence can work in many ways.

CCC: I think you’re drawing a distinction between mass culture with a monetary goal in mind versus art.

Chris Van Allsburg: Exactly. On rare occasions, mass culture even with commercial ambitions, or commercial necessities, can sometimes get close to art-it doesn’t happen very often, but they aren’t mutually exclusive.

CCC: That’s true, and Dickens was writing serial installments for magazines.

Chris Van Allsburg: Extraordinarily popular. In ways that people I don’t think can fully appreciate today. When he came to America and read from The Christmas Carol, he filled auditoriums. He was a superstar. The masses could not wait for the next installment of his work.

CCC: Many of your books have a clear message. You’ve said the stories themselves are often inspired by an everyday observation-we’ve touched on that with Bibot-that you then mull over at night. When a story begins to take shape, do you have a message in mind? Or does it declare itself as you visualize the illustrations and begin to write?

Chris Van Allsburg: Twice I’ve set out to tell a story that embodies a set of values and had a message that I had conceived of before I sat down to write. These two titles by the way would be Just a Dream and The Wretched Stone. Just a Dream was my attempt to contribute to causes that advocate for the protection of the planet-at that point in my life, I was reading Bill McKibben’s The End of Nature. I thought that I could do something personally as an artist. I’m not sure that’s the best motivation for an artist because the message can dominate the story in a way that strips art from it.Nonetheless, I did Just a Dream and tried to tell the story in a way that had certain elements of fantasy. I was trying to create something that wasn’t too grim and depressing, and also to suggest the future could be better if it more closely resembled the past. I was happy with the book, but I knew from the instant I began that I was writing with a goal, an orientation that I’d never had before. It was partly my feelings about that book when I was done, that made me want to write something that was polemical, but also more allegorical, so that as I was telling an adventure story my message was buried a bit more. I wasn’t wearing my heart on my sleeve quite so much and I believed that it was possible to tell a story that was just a rip-roaring tale, but upon completion, you realized that it bore a message, and was, in fact, an allegory. That was The Wretched Stone. Now, nobody over 12 years old has a problem figuring out the allegory and maybe even getting to it long before the story’s complete. For them, it might feel a little polemical as well. When I get mail from younger kids, they’re still guessing about it, but they’ve often got a pretty good idea.

Chris Van Allsburg: Twice I’ve set out to tell a story that embodies a set of values and had a message that I had conceived of before I sat down to write. These two titles by the way would be Just a Dream and The Wretched Stone. Just a Dream was my attempt to contribute to causes that advocate for the protection of the planet-at that point in my life, I was reading Bill McKibben’s The End of Nature. I thought that I could do something personally as an artist. I’m not sure that’s the best motivation for an artist because the message can dominate the story in a way that strips art from it.Nonetheless, I did Just a Dream and tried to tell the story in a way that had certain elements of fantasy. I was trying to create something that wasn’t too grim and depressing, and also to suggest the future could be better if it more closely resembled the past. I was happy with the book, but I knew from the instant I began that I was writing with a goal, an orientation that I’d never had before. It was partly my feelings about that book when I was done, that made me want to write something that was polemical, but also more allegorical, so that as I was telling an adventure story my message was buried a bit more. I wasn’t wearing my heart on my sleeve quite so much and I believed that it was possible to tell a story that was just a rip-roaring tale, but upon completion, you realized that it bore a message, and was, in fact, an allegory. That was The Wretched Stone. Now, nobody over 12 years old has a problem figuring out the allegory and maybe even getting to it long before the story’s complete. For them, it might feel a little polemical as well. When I get mail from younger kids, they’re still guessing about it, but they’ve often got a pretty good idea.

CCC: I saw some of those letters: Is it a TV? I think it’s a TV!

Chris Van Allsburg: It wasn’t specifically TV that I had in mind when I wrote it; it was a glowing screen. So it could’ve been a TV, it could’ve been video games. It could’ve been a computer screen. I think now if I was writing it, I probably would have added that the rock began to glow when it was lightly manipulated with the fingertips so the slightly broader point that I was trying to make would be clearer because I did also see it as a video or computer screen. But by leaving out that digital manipulation part, I think it’s read more narrowly than I would like it to have been read. Maybe future editions, I can add that. It would only be two lines of text.The constant hypnotic state that children find themselves in when they’re playing video games-when even older people, adults, are glued to their computer screens-it absolutely does have the consequence that I describe in the story. Not that it turns human beings into lower primates, but that it kills, literally is death for, all the activities that amused the crew before the stone came on board, which included their pleasure playing music and dancing. They were happy to tell stories to each other about things that had happened in their lives. And they were happy to read and borrow the little volumes from the captain’s library. The death of all those things is the consequence of the tyranny of the glowing screen.Part 2 of this interview is available here. In it, the author continues his discussion of technology and moves on to magic, the inspiration for Queen of the Falls, and influences in his art and life.