Although the assessments in Making Meaning are a natural part of the instruction and very simple to give, the information they glean about students’ thinking is deep and powerful. Often educators feel that an assessment that can’t give a clear number or percentage or that doesn’t state to what level a certain skill has been mastered is not an effective or important test. This could not be further from the truth. As the sociologist William Bruce Cameron said, “Not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts.”

Even though at times it might be important to know how many words out of 100 a child can read, how many letter sounds they know, or which sight words they need to continue to practice, it is equally or more important to know if a child can infer the message an author does not explicitly state in a text. The first set of skills can be quantified with a number so that we know if mastery is being achieved. Skills such as inferring, synthesizing, summarizing, wondering, visualizing, determining importance, etc. cannot be measured in so simple a manner. This has caused many reading experts to shy away from the skills that are not simple to count. Sadly, this is a grave error. The skills that are hardest to count are the reasons we read. We read to learn about characters, to take us to faraway lands, to walk in others’ shoes, to experience things we cannot relate to, to learn, and on and on. But how do we measure a reader’s aptitude in these crucial reading strategies? While it may not be possible to put a simple number to these items, we can take a serious look at how a child thinks about text.

The Making Meaning Class Assessments, Reading Conferences, and Individual Comprehension Assessments give us an important glimpse into a child’s thinking around text. These views into a child’s brain are crucial in planning next steps if we want to develop voracious and effective readers. To see all that Making Meaning has to offer in the realm of assessment, here is a simple comparison. First, read the following story and take the subsequent comprehension test, which will easily give a percentage or number of items scored correctly:

The Flifferfluffs of Whomlam

There once lived four Flifferfluffs. They lived in the lovely country of Whomlam. All four wanted to go on a wanderbuster. On his way up the hill, the first Flifferfluff floofed. The second Flifferfluff fleeplopped beside him while the third went around the beneffely and got lost. The fourth flifferfluff made it to the wanderbuster and had a wonderful time.

Please answer the following questions. If necessary, you may refer back to the story.

- Who were the characters in this story?

- What did they want to do?

- Who made it to the wanderbuster?

- Did he enjoy the wanderbuster?

- What happened to the first three Flifferfluffers?

Give yourself a percentage score. It is clear and simple to get this score, right?

Now take a look at the following three assessments offered in Making Meaning. These are all found in Unit 3 of the Grade 3 Making Meaning Teacher’s Manual.

Class Assessment

After reading The Raft by Jim LaMarche you are to ask students to share with partners the following questions:

- How does Nicky change between the beginning of the story and the end?

- What does Nicky learn or realize that causes him to change?

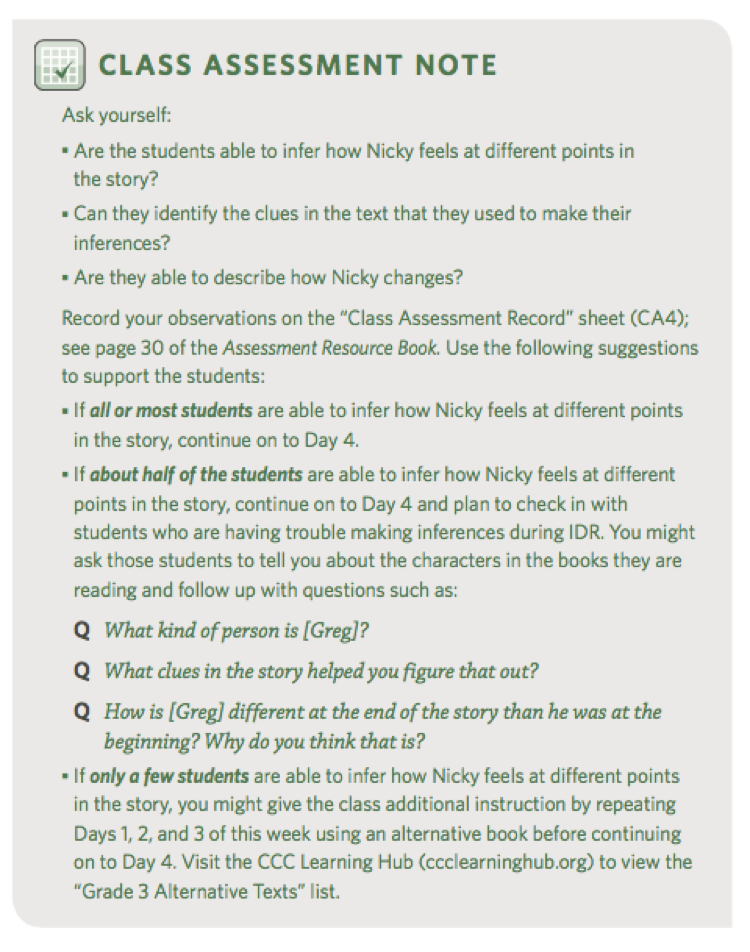

As students share you are to listen in using the following Class Assessment Note:

After taking a serious look at students’ comments, you will have no numbers to quantify your thoughts, but think about all that you will know about your students’ ability to analyze characters while inferring what the author does not explicitly state. More importantly, think about the suggestions at the bottom of the assessment that will guide further teaching so that your students do learn to infer and analyze characters.

Individual Comprehension Assessments, Part A and B

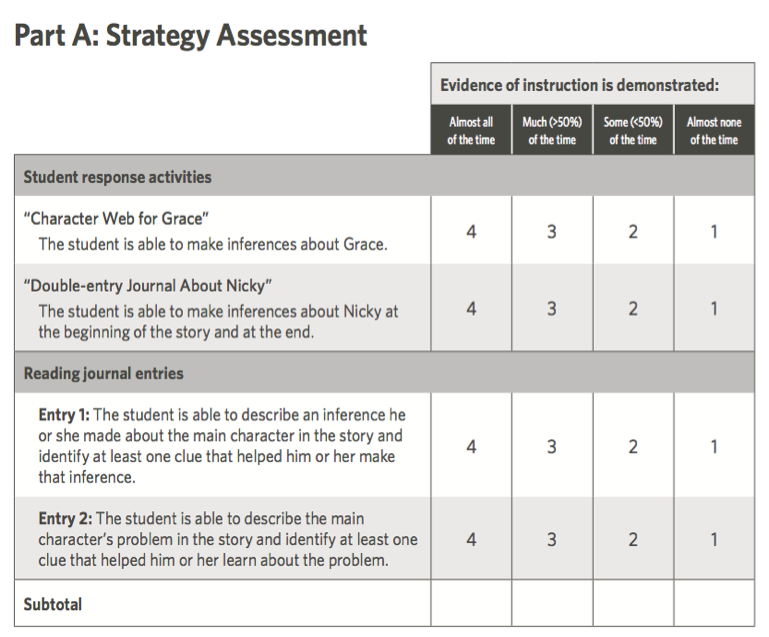

Now let’s take a look at the Individual Comprehension Assessments. First we will look at this unit’s Part A: Strategy Assessment, also found in the Assessment Resource Book.

Each of the above assessments ask students to write about inferences. The “student response activities” are writing activities found in the Student Response Book and are natural extensions of the read-aloud lesson. The “reading journal entries” ask students to write in response to reading in their Individualized Daily Reading (IDR) book. All four of these writing activities would serve to back up what you learned from the class assessment as well as the IDR conference notes.

Before we take a look at Part B of the Individual Comprehension Assessment, let’s pause to consider IDR Conferences. Daily, students are asked to apply their learning during IDR. In the IDR section of the lesson, you are provided with guidance for supporting students to read independently, do or consider something based on their learning, and share their experiences during independent reading. As the teacher, you are asked to confer with students during IDR.

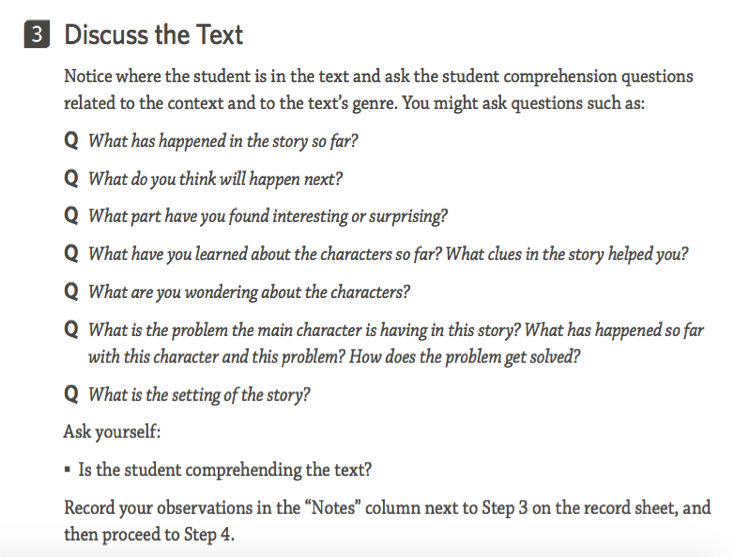

Part three of the Resource Sheet for IDR Conferences, found in the Assessment Resource Book, gives questions you can ask a student during the IDR Conference. As you read these questions, consider how they would help you assess a child’s understanding of character, inference, evidence in text, setting, problem-solution or plot, as well their use of wondering and predicting.

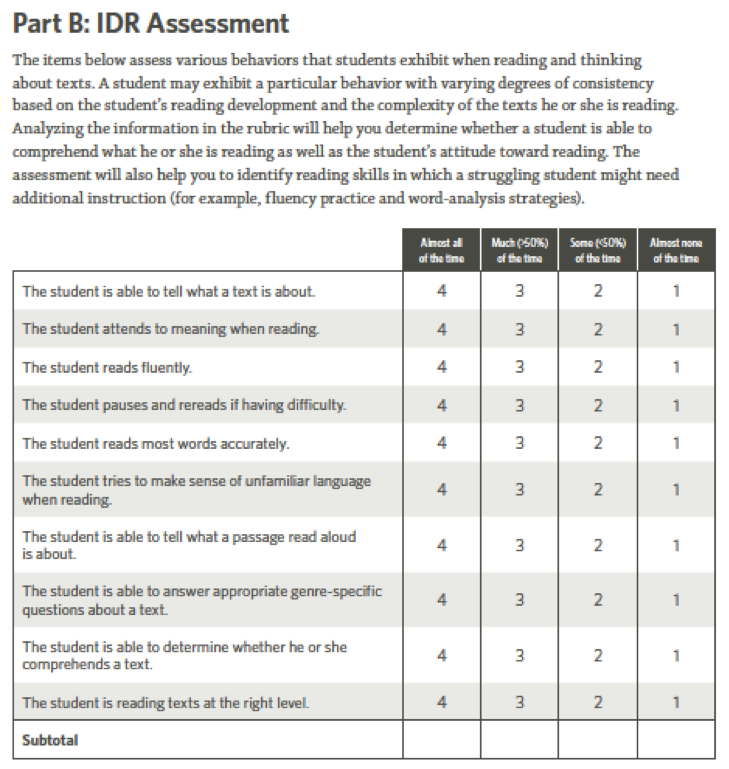

Across each unit, you have the opportunity to collect data on the students through the Class Assessment and IDR Conferences. This data collection prepares you for Part B of the Individual Comprehension Assessments, the IDR Assessment:

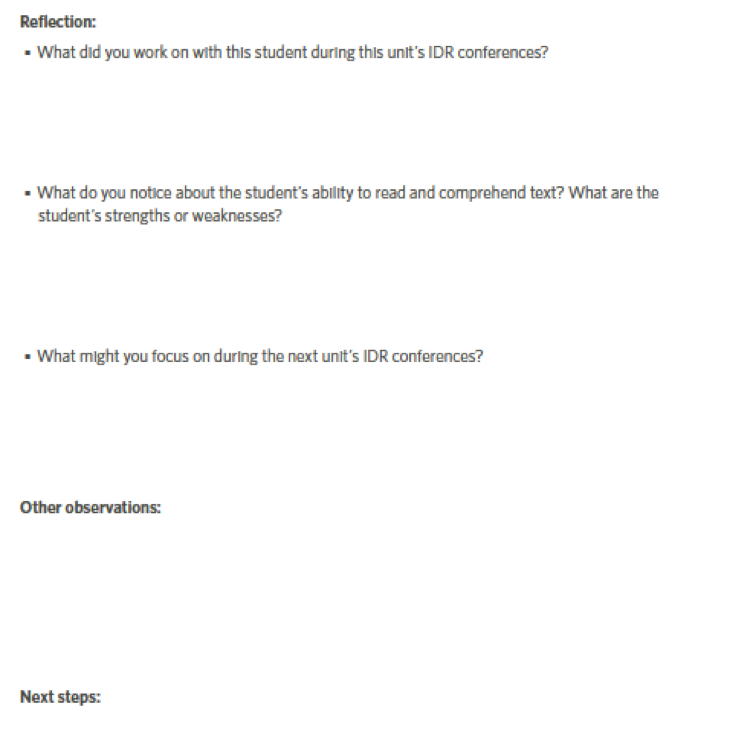

After summing up all of this information, you are given the opportunity to reflect on what you worked on with each student, their strengths and weaknesses, and most importantly, what your next steps will be. This thinking will guide you in tailoring teaching that will take your students to deeper and deeper levels of comprehension.

Conclusion

Wouldn’t these assessments give you a wonderful peek into a child’s brain and how that child thinks about characters? After having a student take a quiz like the one about the nonsensical Flifferfluffs, what would you really know about their use of inferring? Which type of assessment would help you most in planning a child’s or a class’s next steps?

Making Meaning assessments show you how your students are truly comprehending rather than just giving a percentage of how many questions they answer correctly. Start counting what does count and use the Making Meaning assessments to guide your teaching for each and every student. I think they deserve it!

Reference

Cameron, W.B. (1963). Informal Sociology: A Casual Introduction to Sociological Thinking. New York, NY: Random House,