In my previous blog, I addressed text-dependent analysis (TDA) questions and how they require analytical reading before a student can put their thoughts in writing. We explored the idea that in order for a student’s writing to fully answer a TDA question, we as educators must place an emphasis on both reading and writing skills.

Now we must consider how to match our instruction to help students think more deeply about analyzing what they have read in order to write thoughtful essays. We need to explore a question: What kinds of instructional strategies can we use to meet the needs of students who are analyzing texts and writing about reading?

Text-dependent analysis questions generally call upon students to employ close-reading strategies. The term close reading, while popular in discussions about how to help students read in a more analytical manner, can be confusing to both teachers and students if what is being asked is unclear. If there is no intent, no authentic purpose, to what we are asking students to do in the classroom, it might not make sense to us as educators, nor to our students. This is why I prefer thinking about close reading in a more purposeful way as intentional annotation.

When teaching our students about intentional annotation, we should begin by showing its practical applications in our own lives as teacher-learners. By showing examples of when I have needed to annotate for a purpose—such as books I annotated as a learner in my graduate classes, or passages I read for my professional learning community (PLC)—I can show students this is not an assessment-only application or activity. We need to show how intentional annotations are more than something we do to practice for a state assessment; we need to show the authenticity of the act. Kids won’t be engaged in something if they cannot see its intrinsic value.

Aligning What, When, and Why

If we make intentional annotation a regular part of our classroom experience, the when, why, and what of our reading need to align: when the students are reading, they need to know why they are reading and what they are going to do with what they’ve read after they finish. The text and the reader’s need to comprehend the text should determine which strategies are utilized. Instead of “doing” close reading just because it’s a requested classroom task, the students are annotating intentionally because it is going to be helpful to them as independent readers. I want my students to be able to understand and learn from a text while they read and to understand the usefulness of annotation. After reading, they will explore the related task using their intentional annotations. Is that task an in-depth conversation with a partner? A piece of writing that communicates their thoughts about what they’ve read? What are they going to do with the reading once they’ve finished with their intentional annotations?

Begin with the Why

Students should let their purpose for reading a text dictate what they do while they’re reading it. Teachers need to set the purpose for reading the text they have chosen before the students begin to read. We can think of these purposes within two broad categories: learning the content and responding to a specific text-dependent prompt.

Both of these categories lend themselves to certain kinds of annotations. If the purpose is to learn the content, annotations could include summaries, paraphrases, or thoughts that connect the content of the text to other content that was learned previously. If the purpose is to respond to a specific prompt, students should intentionally annotate toward that prompt.

Before we can ask students to make an argument, we must first teach them how to make argumentative annotations, and before we can ask them to analyze, we must teach them how to make analytical annotations. To keep the purpose authentic, we have to address the why with our students: How is this kind of annotation going to benefit them in their lives? To make the task real, I might show them a news article I need to read analytically or a book chapter I need to read with an argumentative stance in order to present an argument to my small group in my PLC.

After Students Read

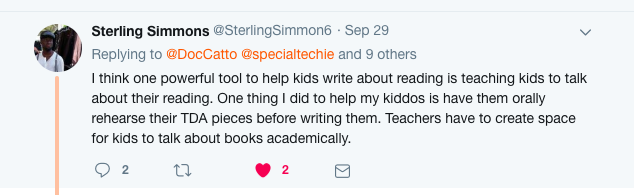

When reflecting on what adults do after we read, I found myself thinking of the variety of activities students can engage in after the reading and intentional annotations are finished. Certainly they can write their response to the text in a journal or paper format. They can also create, post, and reply to others’ BookSnaps, a digital form of annotation and response created by Tara Martin. While it is important for students to be able to respond to a text in writing, it can be equally valuable to ask them to respond orally in small-group or partner discussions. Sometimes it is even better for students to rehearse their responses or reactions to a text aloud before they write about them. Sterling Simmons, a fifth-grade teacher in South Carolina, replied to the first blog in this series and shared his idea of creating the space for students to talk about reading in his classroom:

That is powerful. We should give time and space to honor talking about reading and to practice the strategy of rehearsing something before writing. One digital tool that teachers can utilize for this is Flipgrid, an online video-discussion platform where students can record short videos about what they read and reply to one another’s recordings.

Top Three Points to Remember

Here are the three most important things to remember about intentional annotation:

- It will become busywork if we expect students to do too much of it. We need reasonable expectations and clear explanations of the why behind intentional annotation.

- There must be a balance of intentional annotation and reading for the love of reading. Too much annotation can kill a love of reading. Preserve that independent reading time.

- The point of engaging students in the practice of intentional annotation is to help them internalize their purpose for reading, to support them in reading with that purpose in mind, and then to guide them in writing or speaking in line with that purpose.

The next blog in this series on writing about reading will tackle the specific purposes of learning the content and responding to a text-dependent prompt and how we teach intentional annotation towards each of these purposes.

Click here to download a Being a Writer sample lesson.