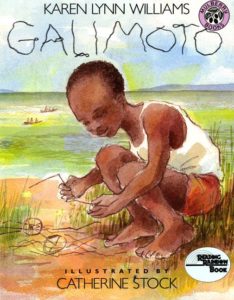

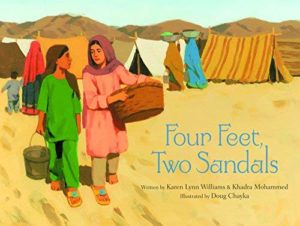

Children’s books are the cornerstone of Center for the Collaborative Classroom’s (CCC) programs; in a way, the authors are our behind-the-scenes collaborators. We want teachers, administrators, students, and parents to be able to learn more about these wonderful authors and illustrators. We are happy to present the next interview in our new series, with award-winning author and teacher Karen Lynn Williams. She has written many beloved books, including Four Feet, Two Sandals, A Beach Tail, Tap-Tap, When Africa Was Home, and Galimoto, which is part of our Making Meaning program. Her new book, Sacred Words, Secret Hero, will be published by Lee & Low in 2017.

CCC: A few years back, you said:

CCC: A few years back, you said: I feel the best parts of who I am come from my childhood.

Could you tell us about your early family life?

Karen Lynn Williams: I should have said, “I was a better person when I was a child.” I was more open and accepting and less judgmental. Putting that aside, I am fascinated by childhood as a time of life and I have a great deal of respect for children and young people. I believe that our childhood shapes who we become as adults. This is one reason I have always wanted to write for children. It forces me to write from and for the child in me. As far as my early family life, my mother suffered from severe mental illness for as long as I can remember. This made a big impression on me. I was very sensitive to her emotional states, and this gave me what I thought of as an extra sense. I was always tuned in, sometimes too much, to what others might be feeling. I think this is part of what makes me feel I was a better person when I was young, the sensitivity I believe I felt toward others. I was also painfully shy as a child even through high school. No one believes that now.

CCC: What were some of your favorite books to read or have read to you as a child?

Karen Lynn Williams: There are so many. My parents were big readers and my mother started me early on books that I was too young for at the time. Books like Van der Post’s Venture to the Interior and The Good Earth by Pearl Buck. We often read out loud as a family. The Incredible Journey by Sheila Burnford is one of the books I remember my father and mother took turns reading to us as my two brothers and I sat snuggled up on the couch. A few other books-of the many that I remember reading as a child-include: The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett, A Girl of the Limberlost by Gene Stratton-Porter, and Little Women by Louisa May Alcott.

CCC: Elementary school teachers have such a profound influence on their students. Can you tell us about one of your favorites?

Karen Lynn Williams: My sixth-grade teacher. He was the first male teacher I had, and I had a secret crush on him. I think all the girls did. We learned how to write short stories in his class, and he let a few students read theirs aloud every Friday. Everyone looked forward to that sharing time. One girl in particular had a unique storytelling and writing talent, and that made an impression on me. That same teacher told us that we had to follow our dreams and it would take blood, sweat, and even tears to achieve them. He confided in us that even he had cried along the way. I never forgot that.

Remember that usually, the more difficult the journey, the more you gain from it. There are no stories without some tension.

CCC: “I want to tell a good story that will capture my readers and take them beyond their own lives.” I read that you wanted to be a writer from the time you were very young. Did you also plan to travel far away and make your home in other countries? What inspired you to think beyond your own life in such a profound way?

Karen Lynn Williams: I always wanted to leave the suburbs of New Haven, Connecticut, when I grew up. I always wanted to do “something different,” although I did not know what that was. I had a longing to travel that my mother instilled in me with those books about faraway places and other cultures. They gave me a great curiosity about the world in general. When I told her this, she was amazed. It was never her intention that I should travel so far from home, but she supported my husband and me in our choice to live overseas. My father enjoyed travel and he encouraged me to see the world as well. I have found that when I live out of my own element, I see things around me in more detail; everything excites and impassions me. However, when I teach workshops, I make a point of telling the students that you do not have to leave town to write a good book. You need to write what you are passionate about, what sparks your imagination and curiosity. All of my chapter books take place in a world that is much like Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and the characters are a lot like my own children and/or the people in my own childhood. This is what I know and what inspired me to write those books.

CCC: What is something you think is important for children in America to understand about children’s lives in Malawi, Haiti, and/or on the Navajo reservation? And vice versa?

Karen Lynn Williams: I think it is important for American children to better understand the history of the American Indian. This is not taught well in our schools, if at all. In fact, a recent survey showed that most American students do not think there are any Native Americans still alive. Or they have an idea about “Indians” from TV and the movies that are not necessarily based on real life. A number of young Navajo have asked me what people in mainstream America think about the Navajo. It is difficult to have to tell them that most of us know little about who they are or how they live. What I have learned about children around the world is that they are generally open and engaged and are excited about learning. They want to understand the world. They are ingenious. They are spontaneous about life and they like to laugh.

I had a longing to travel that my mother instilled in me with those books about faraway places and other cultures.

CCC: At CCC we are dedicated to improving elementary education by creating safe, inclusive classroom environments in which kids learn academics as well as social skills. You must have such an incredible perspective on the approaches to education in cultures around the world and right here in the United States. Could you share your observations? What makes a “good” school, in your opinion?

Karen Lynn Williams: I found in Malawi that teachers are highly respected and education is something students value and appreciate. When I taught there, the high school boys used to run across the street to carry my books. If rainwater dripped through the ceiling onto my lesson plans, they would immediately get up and move my desk without being asked. In rural areas, many families cannot afford the small fee for school and uniforms. The students often missed a term or a year until they could afford to return to school. The “boys” in my high school classes were usually young men in their twenties by the time they reached those higher levels. There could be 40 students in a class. There could be as many as 150 in the lower grades, where students sat on the floor. Much of the learning in both Malawi and Haiti was done by rote memorization. I could hear the chanting of lessons whenever I passed by a school, and in both places, students sat outside under streetlights and recited lessons for homework to prepare for the next day.

What makes a good school? Creative teachers who are passionate about teaching and care about their students, and administrators who nurture that passion, creativity, and caring.

All children are curious and want to learn if given the right environment and stimulus, and a good teacher who fosters the joy of learning. In general, if a child is curious and loves to learn, the rest will follow. What makes a good school? Creative teachers who are passionate about teaching and care about their students, and administrators who nurture that passion, creativity, and caring. I have been to schools around the world as a visiting author and you can tell a “good” school almost from the moment you walk in the door.

CCC: Far more specifically, what do you think about the way Galimoto is used in our Making Meaning program lessons?

Karen Lynn Williams: First I should say that I am delighted that Galimoto is among some wonderful books used in this program. I am also pleased that the program offers a way to deepen understanding of the book-the concepts and ideas presented in the story-more than a simple read-aloud might. I did not write the book to be used as a lesson, but I saw the possibilities and I am pleased that the Making Meaning lessons have extended the value and meaning of Galimoto. It is gratifying for me as an author to see how a book I have written can go beyond the story in a meaningful way when the readers, both children and adults, embrace it and make it theirs.

CCC: In both Galimoto and in Painted Dreams, the protagonists are very resourceful (Kondi is determined to find wire for his galimoto and Ti Marie to find paints for her drawings). Were you resourceful as a child? Could you comment on the concept of play, and of toys, in different cultures and classes?

Karen Lynn Williams: My favorite play as a child involved using my imagination. We built forts under bushes and used dandelion blossoms and leaves for pretend food. An old wooden box made our table. We had adventures in the woods behind my house and pretended we were exploring. Yes, I think I was resourceful in that respect. I enjoyed playing in old dress-up clothes, singing and putting on shows with my friends. The front steps made our theater. Of course, I had manufactured toys and dolls as well. But I did not have all the store-bought clothes for my dolls. At an early age, I learned to make their outfits from scraps of fabric and used buttons and trim. When we returned from Malawi, my own children complained that no one wanted to come to our house because we didn’t have many store-bought toys. But they all played for hours with the old cardboard boxes and cartons I had saved in the basement for art projects. They enjoyed pushing each other over in a refrigerator box or tossing milk cartons into it to see who could make the most successful throws. Play is not structured i n the cultures I have experienced outside of the U.S. In the village where I lived in Malawi, I observed children playing jump rope, but instead of a rope, they used a vine pulled from nearby trees. They played clapping games and they used the sticky mud from termite mounds or the riverbed for clay to make dolls and toy cars and cooking pots. They ran races and danced to the drumbeat of a friend “playing drums” on a trash can. And of course, they made wire toys with scraps they found around the village. They used pebbles to play a game like jacks. The children in Haiti played similar games, and they used certain bones from goats that had been slaughtered for a special meal for their jacks game. They made toy cars like galimotos, but they used old tin cans instead of wires. These kids are resourceful and creative. I observed children who made a pinwheel-like toy by cutting up an old cleaner bottle and then ran around pretending they were airplanes. This kind of play was common in both countries. In Malawi, I learned a lesson. I started giving the children glue and paper and markers, teaching them games, and making pictures with them, looking at books. After a while, I noticed that they hung out around my house waiting for an activity as though they were bored. I don’t think they had ever been bored before. Of course in both countries, there are children who live in cities who have more modern lifestyles. On the Navajo reservation, the more traditional families tell stories and the young people learn to weave and care for the sheep. But since they are also living in the U.S. and not far from stores, they have more access to manufactured toys and video games, if they can afford them, than children in the villages of Malawi and Haiti.

n the cultures I have experienced outside of the U.S. In the village where I lived in Malawi, I observed children playing jump rope, but instead of a rope, they used a vine pulled from nearby trees. They played clapping games and they used the sticky mud from termite mounds or the riverbed for clay to make dolls and toy cars and cooking pots. They ran races and danced to the drumbeat of a friend “playing drums” on a trash can. And of course, they made wire toys with scraps they found around the village. They used pebbles to play a game like jacks. The children in Haiti played similar games, and they used certain bones from goats that had been slaughtered for a special meal for their jacks game. They made toy cars like galimotos, but they used old tin cans instead of wires. These kids are resourceful and creative. I observed children who made a pinwheel-like toy by cutting up an old cleaner bottle and then ran around pretending they were airplanes. This kind of play was common in both countries. In Malawi, I learned a lesson. I started giving the children glue and paper and markers, teaching them games, and making pictures with them, looking at books. After a while, I noticed that they hung out around my house waiting for an activity as though they were bored. I don’t think they had ever been bored before. Of course in both countries, there are children who live in cities who have more modern lifestyles. On the Navajo reservation, the more traditional families tell stories and the young people learn to weave and care for the sheep. But since they are also living in the U.S. and not far from stores, they have more access to manufactured toys and video games, if they can afford them, than children in the villages of Malawi and Haiti.

CCC: Modern life can be frenetic, even for kids-especially when they are scheduled like mini-adults, or when schools feel pressure to accomplish certain tasks within a strict timeline. Many of your books have a gentle, leisurely pace. Even when people work hard, it feels like there is time for life to unfold one step at a time would you say this is the natural pace of childhood or the pace of your settings?

Karen Lynn Williams: I believe it could be the natural pace of childhood if we allowed it to be. Much of what I observed in other cultures is what I imagine childhood was like for my parents or even my grandparents at a time when life, in my mind, was in many ways simpler than it is now.

CCC: All of your stories seem to grow organically from your life experiences. How do you decide which one you’re going to tell? How did you come up with the idea for your very first book, Galimoto?

Karen Lynn Williams: I do not know how I would write other than from my life experiences. I always have a lot of ideas swarming my mind. I usually settle on the one that suggests a more complete story, or the one that best captures my imagination and/or a passion. In Malawi, I was fascinated by the toys the children made out of wires. They were creative and imaginative and the kids seemed to make them out of almost nothing. To me, the galimotos I saw were as much works of art as playthings. I tried to tell a story about these remarkable toys in several ways. First, I wrote an article for a magazine but it was not accepted. Then I wrote about a boy who earns money for school by building a galimoto and selling it. That was a terrible story. Finally I realized that there could be enough tension and an arc in just telling the story of how a child finds the wire and builds a galimoto. I wanted children in the U.S. to know about these remarkable toys, and of course, as a teacher, I knew there were possibilities for the classroom and as a writer, I understood the possibilities for multicultural literature that the story could provide. That book came at the right time for the publishing world. Editors were looking for more multicultural books.

CCC: A Beach Tail captures that childhood feeling of following one’s curiosity, wandering a little farther away from “home” than expected, and suddenly feeling disoriented. Gregory carefully retraces his trail of touchstones on the shore, making his way back to his father, feeling both adventurous and reassured. Could the book also be a metaphor for you? Traveling far from home, observing, creating touchstones, returning to familiar territory, setting out again?

Karen Lynn Williams: I thought I wrote that book as a simple adventure story based on an experience with one of my children who wandered far from the beach blanket. While I didn’t intend it to be a metaphor when I wrote it, I certainly have come to feel it could be a metaphor for life in general. I encourage my readers to adventure from home, but to always know where home is and to return to it. In other words, it is important to explore even if it is just the backyard, and it is also important to know who you are and where you belong in the world-that can change as we grow and change. We are all continuous works in progress. Certainly, reaching outside of my own realm of comfort has contributed to my understanding of the world and of myself and my writing. The choice to make the character African American in the illustrations added another layer to the story about a boy and his father on the beach, one I had not considered but one that readers and educators have embraced.

CCC: Could you describe how you collaborate with the illustrators and editors of your books?

Karen Lynn Williams: I write the books the best way I can. Usually, an editor likes the story, the language, the voice, and the idea enough to take it on and do the work involved to bring the book to fruition. He or she might make comments, suggestions, and criticisms. We work back and forth until we are both happy with the material. A good editor has a concept for the book and is able to bring the writer around to making a stronger story without actually rewriting for the author. After the major rewrites are finished, we work on the grammatical, spelling, and stylistic concerns. The process has changed somewhat over the years. I find that I am not offered a contract as early on in the relationship with an editor as I once was. Now the book has to be nearly perfect before we get to that stage, so I might do several rewrites and never sell a project. It seems that editors have less and less time to edit. They are less able to take on projects they feel strongly about. Instead, they have to sell the idea to members of an acquisitions committee, including the marketing department, before they can accept my book. When I do sign a contract, the editor and art director work together to find a suitable illustrator. Sometimes they ask me for suggestions. But usually, I have to let go of the work and trust their experience and knowledge and vision for a book. I must believe that I have told a story that will evoke the necessary emotion and the best work from an illustrator. If I am lucky, the illustrator brings a new dimension to the book that I had not included in the story-the African American child in A Beach Tail, for example. Or the page at the end of Galimoto without words, where Kondi dreams of what he will make next with his wires. When I wrote Galimoto, I was ecstatic that someone wanted to publish it, but I was afraid no one could do justice to the story and no one would really know what a galimoto was or what it meant to build one. Imagine my elation when I heard about Catherine Stock. She grew up in South Africa and played with these toys as a child. She said she wished she had written the book. I knew it was in good hands. Catherine even went to Malawi to do the illustrations. That is dedication.

CCC: What advice do you have for kids or adults who might want to go outside their comfort zone (whether via travel, writing, or any endeavor), but are a little scared of the unknown? How do you take those first steps in your many adventures?

Karen Lynn Williams: I would have to say, “Just do it.” If you think you might want to do something new and different, follow your nature. You have little to lose, and if you don’t take the first steps you may regret the missed opportunity for the rest of your life. Treat your journey as an adventure with ups and downs. Remember that usually, the more difficult the journey the more you gain from it. There are no stories without some tension. The more you witness and experience the more you have to write about. Take the first steps with some planning and preparation, but don’t get bogged down in the what-ifs.

CCC: What languages do you speak?

Karen Lynn Williams: I studied French in high school and I had a hard time with it. I automatically assumed I was not good at languages; that was a big disappointment because I very much wanted to be fluent in a language other than English. In Malawi, I learned Chichewa. I am sure I sounded illiterate when I spoke, but I could comfortably carry on a conversation and ask the price of tomatoes in the market. I could even make jokes. Immersion in a language is the best way to learn it. I learned to dive in and not worry about or feel embarrassed by my mistakes as long as I could make myself understood. Certain strategies became apparent to me. For example, if I could not say exactly what I wanted to say, I could make the same point using the words and language I did have to share an idea. I used those strategies to learn to speak Haitian Creole in Haiti. It is interesting to note that because Creole incorporates French, as well as some African words and Spanish, my high school French, came flooding back to me and it helped me with the language in Haiti. My French improved as well, although I believe that a native French speaker would laugh at that suggestion. I think it would be fair to say that both Chichewa and Creole have less complex grammatical systems than some western languages, and use a phonetic system when written, so in some ways, it was easier for me to learn those languages.

CCC: After experiencing unfamiliar cultures outside the United States, you’ve settled into one right within our borders: living on the Navajo reservation in Arizona must be a little bit like being in another country. Can you share some of your experiences?

Karen Lynn Williams: Because we are still in the U.S., living on the Navajo reservation is like having a foot in each world. It is too easy to go off-reservation for shopping, R and R, cultural events, skiing, hiking, and visiting friends and relatives. When we lived overseas, by necessity, we immersed ourselves totally in the new culture. In Malawi and Haiti, we lived in village areas with open-air markets where neighbors met daily and I could better interact. That is not the case on the reservation. Here the homes are scattered all over. Many Navajo speak English, and we live in a community with doctors and other hospital personnel from outside the reservation who all speak English. On top of that, Navajo is one of the most difficult languages to learn. Few non-Navajo ever master it. I have not been successful, and because language is so closely related to culture it has been difficult for me as a writer to connect to the Navajo world. Navajo are pretty reserved and are used to having people come to work here and stay only a short time. It took two years to prove we were not leaving, to gain trust. I find that the longer we stay, the more open people are. Having said that, I have made a great effort to learn as much as I can about Navajo life. I follow my own interests and have learned Navajo weaving; that inspired me to learn everything about sheep-for example, lambing, shearing sheep, carding and spinning the wool. In this way, I have met several Navajo who have become friends. I have also made friends through my pursuit of other artistic interests-silver-smithing and different forms of jewelry-making and painting. By exploring the Canyon de Chelly, hiking with Navajo friends, and learning about customs and foods, I have learned their stories. We are pretty isolated living in the middle of the reservation, and we picked this location because we wanted as much of the Navajo experience as possible.

CCC: What lingers on with you in your heart or mind-from each of the places you’ve called home? What have you been happy to let go?

Karen Lynn Williams: Of course the people we met and friends we made remain the most important part of our experiences overseas. I have learned more from them than I have ever given. I have never been able to recreate the slower, simpler life that I lived in Malawi and Haiti, where we did not always even have electricity. It is not necessarily an easier life, but there was a different pace and we made do with what we had. We had to be more resourceful, too. The isolation is something I do not necessarily miss-and the constant heat. I have always enjoyed returning to climates with four seasons. I guess whenever I leave “home,” I appreciate it more when I return, at least until I get the itch to travel again.

I am constantly amazed by the reaction of readers when they see themselves in a book.

CCC: The lack of diversity in children’s literature is getting a lot of attention. There has been a tiny improvement in the number of books by and/or about people of color (14% in 2014, up from 10% in 2013, according to the CCBC statistics), but obviously we have a very long way to go-especially considering that according to Census estimates, about half of America’s five-year-olds are members of racial or ethnic minority groups. What are your thoughts on the importance of diverse books for children, especially in schools? Do you have any stories about how editors responded to your books when you started publishing them in the early ’90s versus now? Did you face any challenges as a white woman writing mostly about children of color?

Karen Lynn Williams: I am constantly amazed by the reaction of readers when they see themselves in a book. This is very important, especially for students outside the mainstream population. I spoke on a university campus once, and after the presentation, a young woman came up to me to share an experience she had with one of her peers, a student at that university, a young man from Malawi who was a football player. They had been assigned in an education class to find a picture book to present. This young Malawian found Galimoto. He had tears in his eyes as he reported to her that this was the first time he had ever seen a book about his childhood. When I shared this same book at a workshop for parents and teachers in an elementary school, some parents from Vietnam were excited to tell me that the story reminded them of their childhood. Even though they were not from Africa, they could relate to Kondi and wanted to share that with their children.

I became involved with refugees in Pittsburgh and wrote Four Feet, Two Sandals after the coauthor Khadra Mohammed told me that a refugee child she read to as a volunteer wanted to know why there were no books for children like her. Diversity is not just about skin color or culture. I shared One Thing I’m Good At (about a girl who has trouble reading and learning) at a school. After everyone had left the auditorium, a shy fifth-grade girl came up to me and reported that she was a lot like that girl in the book, and she had never read about anyone like her before. She wanted me to sign her book. At a workshop, for adults, I shared the same book. One attendee suggested that her granddaughter would not be interested in that book because she did not have those kinds of problems. I was speechless. Do we read only to know about ourselves? I suspect that woman’s granddaughter was sitting in class with at least one student who had similar problems to the character in my book. When I wrote Galimoto, we were in a golden era of publishing for children. Multiculturalism was on the rise in schools and in the publishing world. That book has been selling well for 25 years. Today, the industry is driven by the marketing departments and a perceived notion that customers want short, snappy picture books that do not explore the deeper concerns of a multicultural world. I have noticed that many picture books with multicultural characters today are “everyday” stories where the main character who is of color could be anybody. Of course, it is not a wrong idea to suggest that children of various cultural backgrounds are similar to the children of the dominant culture in many ways, with similar problems, needs, and concerns. In fact, there is a need for books that show the “good” things about other cultures, slice-of-life stories, not just the struggles and conflicts. This is one reason I think readers embrace Galimoto and Tap-Tap, for example.I have been working on a book about a child of undocumented parents. It is a story about a boy who cannot go to a soccer tournament because his father is fearful that the family will be exposed. His team votes to stay home from the tournament in solidarity with their teammate. It is a simple picture book about the tension in his life and what his American friends learn from his situation. I cannot find a publisher who is interested in the topic. I suspect the subject is too controversial. Or maybe I have not told the story well enough. On the other hand, since I have moved to the southwest, I am aware of how this book would resonate with many readers. The challenges of a white woman writing about children of color? I agree that there should be more writers of color telling their own stories. On the other hand, I am writing from my experiences in other cultures on topics about which I am passionate about. Initially, I knew I could be criticized for the type of books I write, but I seemed to have found a niche and I have had very little criticism. Some people assumed I was black. Before I had a website with a photo of myself, I know when I went to schools people sometimes thought I would be African or African American. One boy, the only one in the whole school who had a copy of Galimoto before I arrived, was in second grade. He raised his hand and said he expected me to be black. He wanted to know why they never had black authors come to their school. I am sure he is not the only one who has felt this way. I grew up with the debate about who should write multicultural books. For me, it began when there was a need for readers in elementary school to include people of color in the late fifties. In the Ted and Sally reading books, the initial response was to just color in the faces of several characters to make them appear to be African American. After Galimoto came out, it received a glowing two-page review in the New York Times Book Review. I later met the reviewer, who was obviously shocked that I was a “white lady.” She was, however, very gracious. I believe I am sensitive to the concerns in this debate. I do the research and tell the best story I can.

When I wrote Galimoto, we were in a golden era of publishing for children. Multiculturalism was on the rise in schools and in the publishing world. That book has been selling well for 25 years. Today, the industry is driven by the marketing departments and a perceived notion that customers want short, snappy picture books that do not explore the deeper concerns of a multicultural world. I have noticed that many picture books with multicultural characters today are “everyday” stories where the main character who is of color could be anybody. Of course, it is not a wrong idea to suggest that children of various cultural backgrounds are similar to the children of the dominant culture in many ways, with similar problems, needs, and concerns. In fact, there is a need for books that show the “good” things about other cultures, slice-of-life stories, not just the struggles and conflicts. This is one reason I think readers embrace Galimoto and Tap-Tap, for example.I have been working on a book about a child of undocumented parents. It is a story about a boy who cannot go to a soccer tournament because his father is fearful that the family will be exposed. His team votes to stay home from the tournament in solidarity with their teammate. It is a simple picture book about the tension in his life and what his American friends learn from his situation. I cannot find a publisher who is interested in the topic. I suspect the subject is too controversial. Or maybe I have not told the story well enough. On the other hand, since I have moved to the southwest, I am aware of how this book would resonate with many readers. The challenges of a white woman writing about children of color? I agree that there should be more writers of color telling their own stories. On the other hand, I am writing from my experiences in other cultures on topics about which I am passionate about. Initially, I knew I could be criticized for the type of books I write, but I seemed to have found a niche and I have had very little criticism. Some people assumed I was black. Before I had a website with a photo of myself, I know when I went to schools people sometimes thought I would be African or African American. One boy, the only one in the whole school who had a copy of Galimoto before I arrived, was in second grade. He raised his hand and said he expected me to be black. He wanted to know why they never had black authors come to their school. I am sure he is not the only one who has felt this way. I grew up with the debate about who should write multicultural books. For me, it began when there was a need for readers in elementary school to include people of color in the late fifties. In the Ted and Sally reading books, the initial response was to just color in the faces of several characters to make them appear to be African American. After Galimoto came out, it received a glowing two-page review in the New York Times Book Review. I later met the reviewer, who was obviously shocked that I was a “white lady.” She was, however, very gracious. I believe I am sensitive to the concerns in this debate. I do the research and tell the best story I can.

CCC: What book project(s) are you working on now?

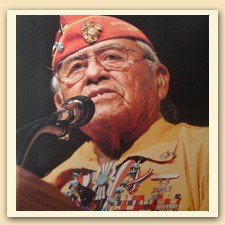

Karen Lynn Williams: Along with many other projects for children and adult readers, I have been working on a picture book, Sacred Words, Secret Hero: The Story of Teddy Draper Sr., Navajo Code Talker, on and off for almost four years. I have sold the book to Lee & Low Books, and it will be published in Spring 2017. Teddy Draper is 93 years old. His story-from boarding school, where he was forbidden to speak his own language, to life as a marine, where he was expected to use his language in code to help defeat the enemy in WWII, to his return to the reservation, where he developed a program to teach young people their native language has a natural arc to it. It is a story of sacrifice, bravery, and heroism.

Karen Lynn Williams: Along with many other projects for children and adult readers, I have been working on a picture book, Sacred Words, Secret Hero: The Story of Teddy Draper Sr., Navajo Code Talker, on and off for almost four years. I have sold the book to Lee & Low Books, and it will be published in Spring 2017. Teddy Draper is 93 years old. His story-from boarding school, where he was forbidden to speak his own language, to life as a marine, where he was expected to use his language in code to help defeat the enemy in WWII, to his return to the reservation, where he developed a program to teach young people their native language has a natural arc to it. It is a story of sacrifice, bravery, and heroism.