Children’s books can create long-term empathy, love, and understanding among people.

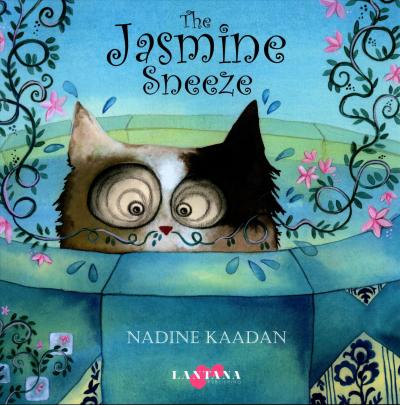

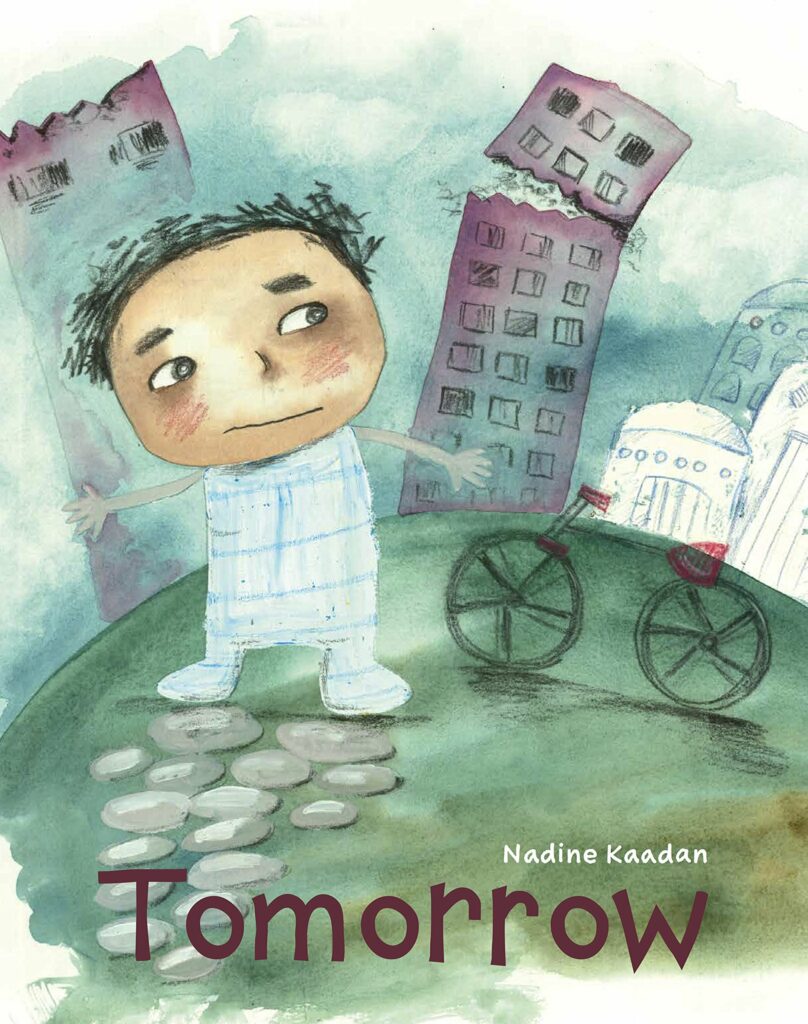

Nadine Kaadan is an award-winning children’s book author and illustrator from Syria currently living in London. She is published in several countries and languages. Her books in English include The Jasmine Sneeze and Tomorrow, as well as Saving Stella (by Bassel Abou Fakher and Deborah Blumenthal), which she illustrated. She has been featured in Marie Claire Arabia, nominated for a Kate Greenaway Medal, and is the 2019 winner of the Arab British Centre Award for Culture.

Nadine was also selected as one of BBC’s 100 ‘most influential and inspiring’ Women of 2020 and was featured in their BBC 100 Women Masterclass. The Jasmine Sneeze will be part of Collaborative Classroom’s Being a Writer program, 3rd edition. The following interview is adapted from our recent conversation.

Collaborative Classroom: Congratulations on your many recent honors, including being selected as one of BBC’s most influential and inspiring women of 2020. In the Millie podcast you said (and I am paraphrasing) that the award lends importance to diversity and to children’s books; that these early stories make us who we are; that you truly believe that the end of racism starts on the bookshelf.

Could you expand on those comments regarding the impact of children’s literature on human understanding, and also share what this award means for you personally?

Nadine Kaadan: Beautiful question. When I found out that I was on exactly the same honor list as all of these formidable women—even Sarah Gilbert who created the COVID vaccine in the UK!—I couldn’t believe it.

But the most important thing, for me, was the reminder to everybody that the impact of an author of children’s books is as important as the impact of an environmental activist or a vaccine researcher. Children’s books can create long-term empathy, love, and understanding among people. Stories shape our identities.

I think a lot of racism starts with fear about what’s different from us, but when you wake up to the world early by reading about people around you, when you love a character that is from a different culture, or you find yourself in that character, you build empathy and love. The more that children’s books provide windows to the world, the more we can find an empathetic world.

[W]hen you wake up to the world early by reading about people around you, when you love a character that is from a different culture, or you find yourself in that character, you build empathy and love.

When the BBC list came out, I felt that it said, “Let’s remember how children’s books are important, let’s honor them, put them to the fore, and bring more attention to them.” I was really, really happy.

Collaborative Classroom: I’d like to continue that theme with something you shared in the BBC interview, but I will preface it by saying that in the US, as the publishing industry starts to address the lack of representation in children’s literature and schools try to expand the range of texts in their classrooms, there can be a bit of a rush to act, sometimes without as much reflection as is needed.

When that happens, the books—as a group—may inadvertently reinforce stereotypes or flatten the stories of historically marginalized people. With this in mind, I was struck by your statement “there is a fine line between pity and empathy” and would love to hear more about this distinction and how we can avoid pity in favor of empathy.

Nadine Kaadan: Yes, I find this to be such an important point; I literally want to scream it from the rooftop! When we think of cultural diversity, when we want to represent a character from a certain culture, we have to remember that this character needs to be empowered—someone that we relate to rather than pity.

And what is happening at the moment is that a lot of books with amazing intentions—for example, raising awareness about refugees—very often are about this sad little boy or little girl who is a refugee, who needs help, and then kind White people help and then their life is better.

These kinds of narratives are really problematic because they completely forget how empowered these people are—the resilience, just for example, to leave a war and walk or travel by sea to find a better life. That, by itself, shows their empowerment.

Of course these people need help, but they also have a lot to give. Let’s celebrate their cultures, let’s celebrate their personalities, let’s celebrate what they have to offer.

We all know what diversity does to a community. It makes it richer, it makes it more exciting, it makes the world more colorful.

If we put them in the background and only focus on what they need, that is a kind of neo-colonialist approach to seeing them: “Let’s help.” It creates a hierarchical relationship, rather than one in which they take—yes, they need help—but in return, they give culture, they give diversity. We all know what diversity does to a community. It makes it richer, it makes it more exciting, it makes the world more colorful. So, it’s not the one-way relationship that most stories present.

Collaborative Classroom: Turning to The Jasmine Sneeze, this book features Damascus—the city you love—a grumpy cat, beautiful fountains, and jasmine, of course. It is whimsical, lighthearted, and, to the point that you were just making, a contrast to the shadowed side of Syria we usually see. This book provides a sense of community, brightness, humor, and a solvable problem that children can easily follow and laugh about.

You’ve said that the publication of a book like this “reminds us not to let a conflict color an entire culture . . . one that comes from an enormous and beautiful heritage.” What are some things you wish were more widely known about Syria and its people?

Nadine Kaadan: I love your reading of The Jasmine Sneeze; it reminds me how much I enjoyed writing it, and how much I needed to do it. To be honest, as is the case for most of my books, I really wrote it for myself. It was a reminder of what Damascus is, of what Syria is.

Nobody knows the true age of Damascus; it’s the oldest city in the world and has gone through so many wars—they come and go—but what stays is the culture and the richness and the heritage and the beauty of this city.

When I left Syria and came here to London, people only saw me as a person who left their own country because of war, and that’s how I saw myself, because that was the dominant thing happening in my life. I wrote The Jasmine Sneeze to remind myself of who we are and the culture that we come from. It was also a nostalgia for our ancient city that I missed so much.

I wrote The Jasmine Sneeze to remind myself of who we are and the culture that we come from.

Living here in a big city like London was a complete shock and different from living in Damascus where you literally know everyone; the small alleyways are thousands of years old; and there are ancient houses, courtyards, and fountains. I needed to process it and put it in a book. What has been beautiful for me to see is that the book isn’t only for me: Syrian children need to see Syria and remember who they are, as well. It is also for non-Syrian kids and adults.

At a Cambridge Literature Festival book reading, I was surprised to see two couples without kids in attendance. They said it was because they wanted to hear about Syria from a different perspective—one that is not the news, has no agenda, and is just about this country. The book gave them a window that the media is not showing at all.

Collaborative Classroom: That goes back to your first point about the impact books can have.

Nadine Kaadan: Yes. For example, to me it’s very clichéd to say that Damascus is the city of jasmine. It’s just something that we lived with.

But then I realized that it’s not a cliché here in the UK. A lot of people have the idea that Syria is a desert, and they would tell me, “We didn’t know it’s the city of jasmine!” I was shocked—desert? OK, we do have a desert, but it’s a small part of what Syria is, and Damascus is a city full of jasmine and roses and orange trees, and we have mountains and beaches and rain. It’s a very multi-seasonal country.

So, a lot of stereotypes were broken in a simple story, which, to be honest, was not my intention. I was just writing about a city that I miss, thinking about a culture that I love.

And that’s the importance of authenticity. When you ask someone to write about their own country, where they were raised and have lived, the authenticity is there because they write about their childhood, their memories, about what they know.

Something that’s happening a lot in the publishing industry is someone who’s not from a region writes about it. I’m not against that; writers should write about whatever they want, of course, and they should not limit themselves to the country they come from.

But when you’re away from a culture and you don’t have that deep understanding of it, this is when lack of authenticity and stereotypes happen. I find that a lot of current books about Syria really have an authenticity problem. I’m happy that this book came out to break some of those stereotypes.

Collaborative Classroom: We are too. The Jasmine Sneeze will be a “mentor text” in our Being a Writer program—helping us to introduce fiction elements like setting and plot, among other things.

Stories your mother told you about her grandmother’s beloved jasmine tree gave you the idea for this story. But how did you create this particular plotline with the cranky cat, his nose sprouting with jasmine (!), smelly fishbones, etc.?

Nadine Kaadan: It’s funny—when I go to schools, I talk about plot and how I write stories, and because I’m an illustrator and a visual person, I see images. I illustrate and the illustration tells me the story. Some teachers are surprised. They tell me, “Well, we usually teach the children to do the opposite.”

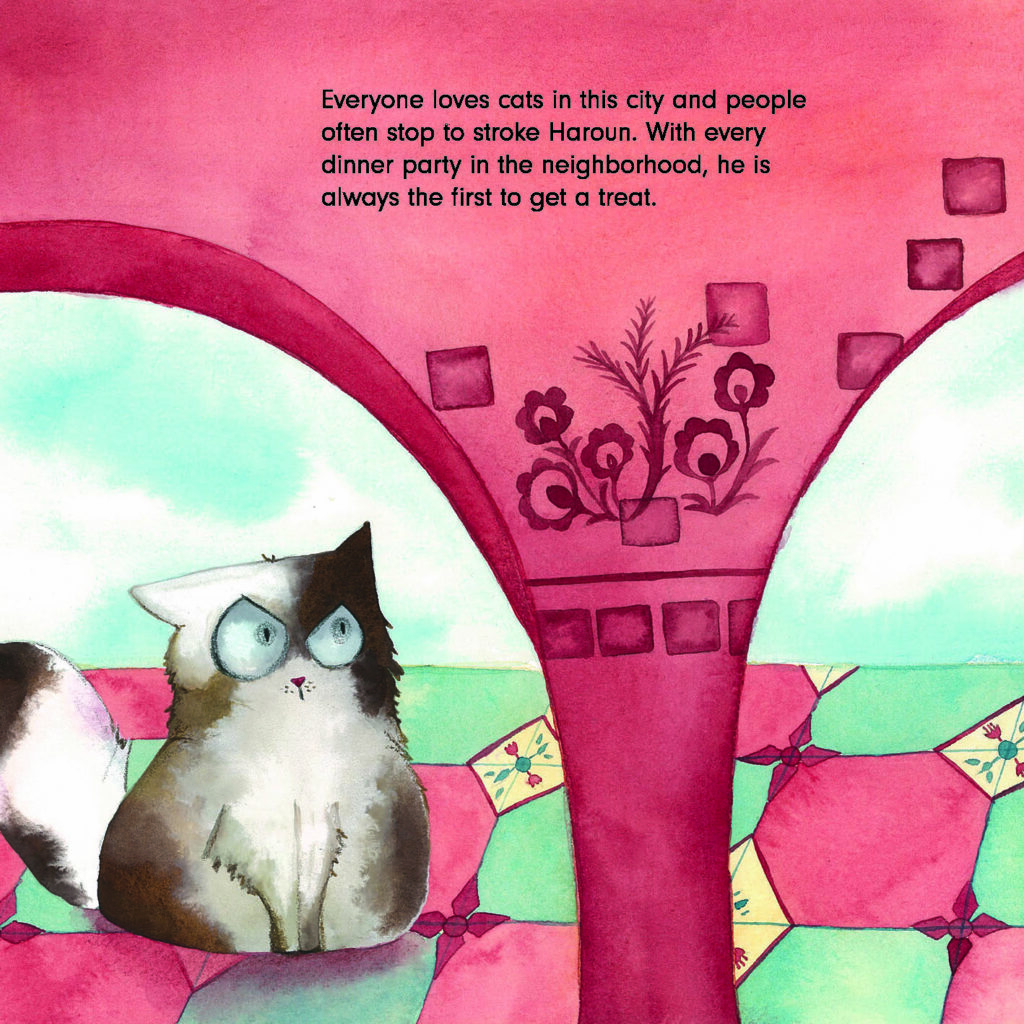

So how did I come up with the plot of The Jasmine Sneeze? I was just illustrating a cat, a jasmine tree, a fountain. That’s what Damascus is. You walk in the old city and you find lots of cats, lots of jasmine trees, lots of fountains, lots of arches and courtyards.

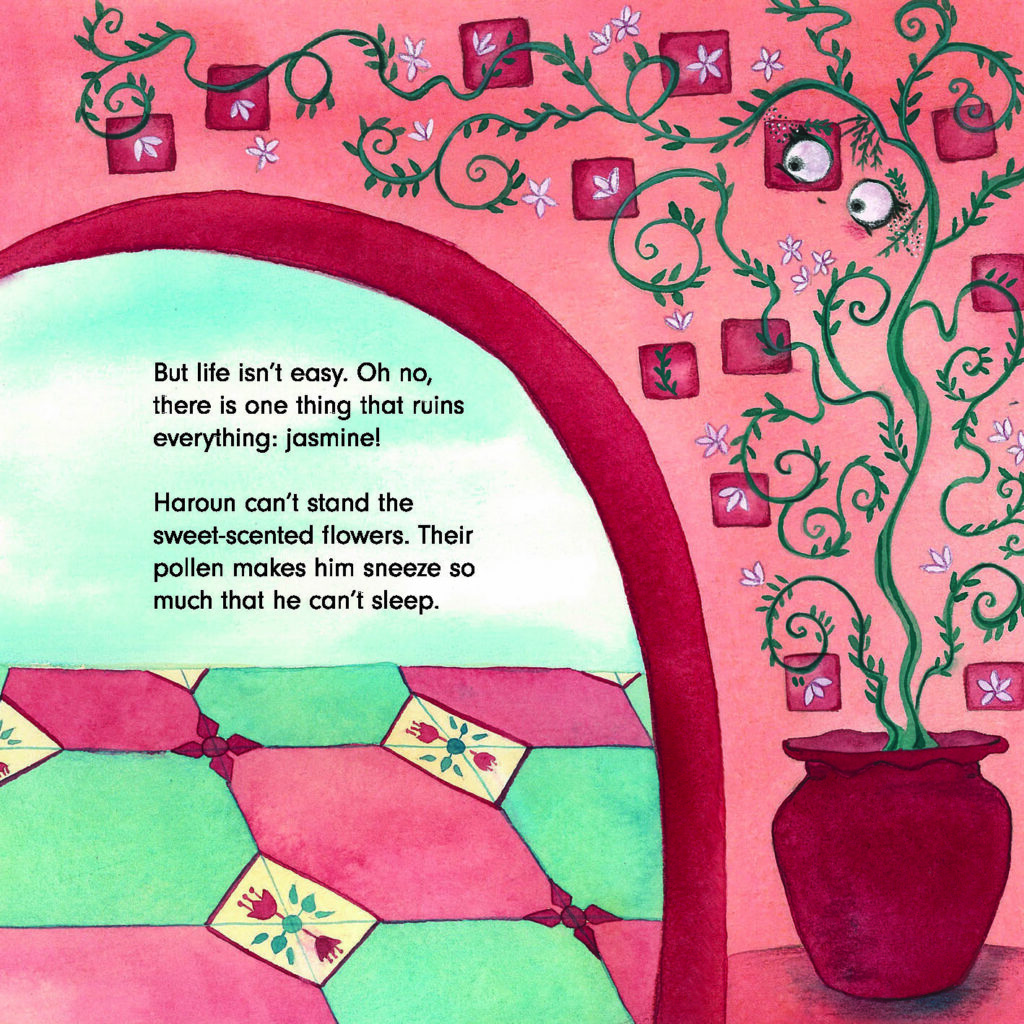

Somehow the cat looked grumpy in the illustration, and jasmine was everywhere, so I looked at it and immediately felt that this is the character of the cat: He’s grumpy, he’s lazy, and he doesn’t like jasmine. But why doesn’t he like jasmine? I went through three or four different scenarios that show why he doesn’t like jasmine—because it’s everywhere, or because he’s allergic, or because it makes him sneeze, or because he doesn’t sleep. When I write, I imagine different scenarios, and each scenario will lead me somewhere, some to a closed door. When I find the scenario that leads me to a beautiful ending, I go for it.

In The Jasmine Sneeze, I went for the scenario in which the jasmine makes him sneeze. Also, the jasmine spirit had different scenarios. In the beginning, I said, “OK, the jasmine makes him sneeze, so he needs to get rid of it, but then what will happen?” I thought of the jasmine spirit, because everybody thinks that the jasmine interacts with people. In the beginning, the jasmine spirit was a woman, an old lady, because in my mind the spirit represents Damascus and the city itself is old.

But then I realized, no, because the spirit, the city, has always been here, maybe the spirit is always young—let’s turn it all upside down. So actually, she’s a girl who gets angry quickly and who forgets quickly. The story went through a lot of changes to arrive at what it is now.

Collaborative Classroom: Many people, many children, move to the US and English is their second or third language. How do you approach writing in multiple languages? When you start to write the story, do you begin in Arabic and then move into English? Do you think in English now? How does that work?

Nadine Kaadan: I first wrote The Jasmine Sneeze in Arabic, because it’s the language of my childhood and my memories, so I felt I could express myself better in it.

Once the story was finished, I rewrote it in English. But I don’t do that anymore. If someone is bilingual and English is their second language, I would say, yes, in the beginning, do that—then slowly English will become the language you think in and it will become much more natural to you. So now I write in English. Still, sometimes I feel like I can express myself better in Arabic. It’s funny—I feel like I’m two different people now. The person who writes in Arabic is different from the one who writes in English.

Collaborative Classroom: Thinking about language, I’m quoting some of yours: “the jasmine scent covered him like a blanket,” and “. . . he looked at his bike and was tempted by its shiny red paint and its new bell that made four different sounds. TINGALINGALING!”

Sensory details are powerful; we encourage students to use them in their writing and it’s often the kind of language that’s added in revisions. Could you tell us about your writing process—in particular your approach to word choice and concrete details as opposed to vague language—and then how you go about revising and the importance of revision in your work?

Nadine Kaadan: Wow, that’s a really powerful question, and not easy to answer. Just to mention that bicycle with four different sounds—when I was a child of eight or nine, my cousin got a bicycle with four different sounds, and I was jealous because my bicycle only had the normal ring. So, I needed to put that in the book to remember how important that bell that I didn’t have was.

But, to answer your question: I start writing by telling the story to people around me. I bring in a friend, my husband, my sister, or my son, and ask, “What do you think of the story?” If I tell it and people can listen to it from beginning to end and enjoy it, then I feel like it’s ready to be written.

I tell myself, “I’m just going to write a silly story. I don’t care; I’m going to write a boring, silly story.” I do this because if you go to an empty page with the mindset of “it’s time to write a good story,” that’s very intimidating. It’s very scary, and you might not be able to finish; you might get stuck.

So just tell a simple story. Put it on paper. I remember Neil Gaiman once tweeted, “The worst first draft you ever write is the empty page.” That’s very encouraging.

I start by just writing it down, and then I slowly look at the details and try to use my memory and my childhood as much as I can, stories and details that I find exciting. It’s as simple as that. And I always say, if it has excited me, maybe some children will get excited about these details, whether they’re about the bell with four different sounds or the feeling of the jasmine scent that covers you.

And revision? It’s really important not to be precious about the stories that we write. Many people, when they write a story, get so attached to it that it’s hard to change it. I understand; I was like that. But when we let go, we may be surprised with how much more interesting and fun it can be. We have to be willing to just break it and redo it. We need to edit and rewrite and revise.

But when we let go, we may be surprised with how much more interesting and fun it can be.

After finishing a story I always ask myself, “Can I turn it upside down? Can the ending be the beginning? Can the middle be the end?” I play with it and decide which one is the better version. For me, that’s the most fun part of writing because you don’t know what’s going to come out of it, and you just give it a go!

Collaborative Classroom: What you’re describing is having the confidence and the trust in what you find interesting, or what moves you, or what’s in your life. Yet developing story ideas and having the confidence to explore them can be challenging and intimidating. Can you say any more about what inspires you, in addition to your memories?

Nadine Kaadan: As a writer, as someone who’s in a creative field, you wake up with a new idea every day, but how do you decide that this idea should be a book? Where does that inspiration come from?

For me, it’s purely passion. If there is a topic that I’m so passionate about that I’m willing to spend the next few months with it, then that’s enough reason for me to write about it.

It’s as simple as following the things you really love and are curious about. The thing you write about doesn’t have to have happened to you—it can be something that happened to someone else—but you need to love it and be so passionate about it that you’re willing to write it, and rewrite it, and rewrite it, and rewrite it, and keep focusing on every letter and every word until it’s a good story.

Collaborative Classroom: Let’s talk a little bit about some of your other books. You’ve written and illustrated fifteen in Arabic, and at least two in English so far.

I read that your very first children’s book, Leila Answer Me (which was in Arabic) is about a deaf princess. How did that come to be?

Nadine Kaadan: The story of the deaf princess came from a personal experience. I was at a biennial children’s book illustration workshop in Bratislava where they bring illustrators from all over the world to learn how to do children’s books.

One of the illustrators was deaf, and she was signing with her friend during the workshop. Because I don’t speak sign language, I was intimidated; I didn’t approach her. I became friends with all of the illustrators except her. I tried to talk to her, but I felt scared, so I didn’t have as deep of conversations with her as I did with the rest of the illustrators.

After I went back to Syria, we exchanged emails and then started writing to each other. I realized, “Oh my god, this person is so witty, so funny, so clever.” She is now a good friend—we became so close; she is closer to me than anyone else from the workshop. And to think that I almost missed the opportunity to have a wonderful friend because I was scared of something that I didn’t know, that I would do something wrong.

That leads us again to what I said before about how we are scared of things we don’t know and that’s why we need to read about them. So, she inspired me to write this book. I wanted children to know that different languages shouldn’t make us afraid to try to communicate. Some people speak in a sign language. That’s beautiful and we can just approach them and try to learn and not let things that we don’t know about scare us.

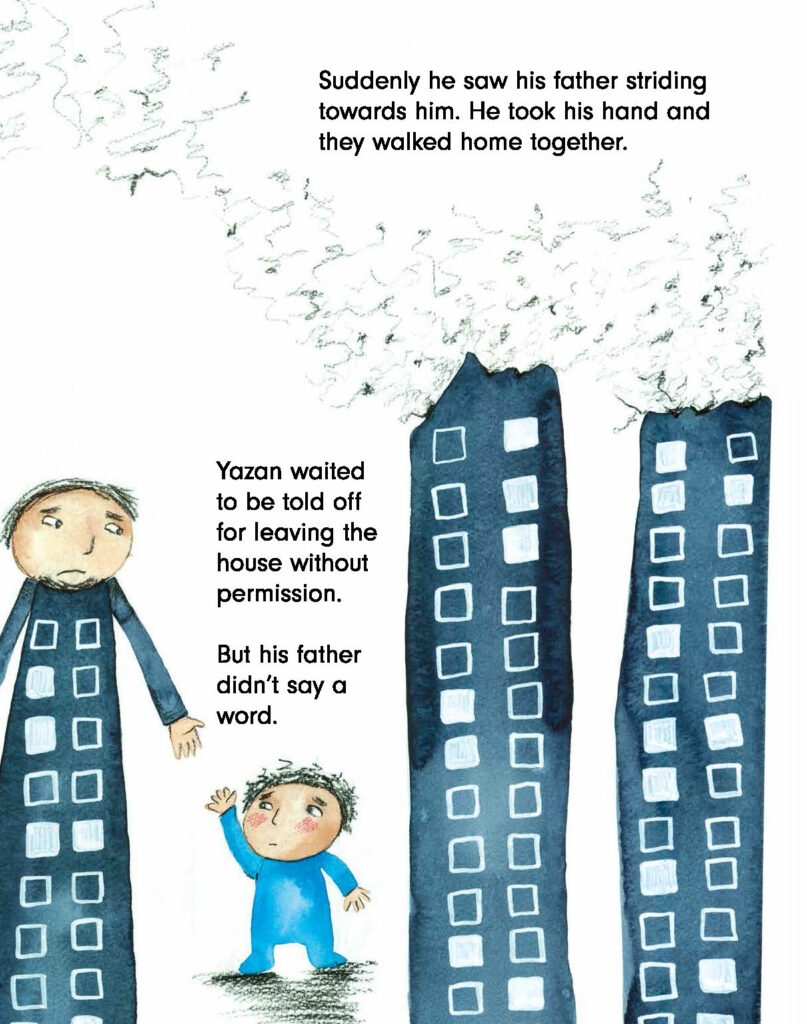

Collaborative Classroom: Another book, Tomorrow, which was originally published in Arabic in 2012, and then in English in 2018, is about a little boy named Yazan whose life is changing because of the war in Syria—no more going to school or the park or bike-riding. And then, perhaps more heartbreaking and a little scary, he sneaks outside hoping to find the life he’s been missing. He finds instead that nothing is the same.

It’s a crushing moment and reminded me of conversations I’ve had with writers and colleagues at Collaborative Classroom about how to balance the darker parts of life in children’s books. What is your opinion on that topic? What’s appropriate to share when you’re writing about difficult things?

Nadine Kaadan: That’s a very, very good question. When I created the book—with all of that dark illustration and the scene you mention when Yazan sees his country differently—I felt brave because I wasn’t thinking, “Will it be published? Will it not be published? What will people say? Is it appropriate? Is it not appropriate?”

I just did it as a way to process what was happening: I suddenly woke up to find my city going through war, and I needed to process it in a story. I found my style of illustration had changed, and I just let it out.

When I read it with kids in a refugee camp in Lebanon, I didn’t know what to expect. I just showed up with a box of chocolates and didn’t know what to do. It was shocking for me, to see first-hand the importance of showing the reality of children in a book, to tell them that they’re not alone, that there are so many kids who are going through what they are going through, to tell them, “You’re seen and acknowledged.”

I did my Master’s in Art and Politics, and one of the courses was about memory and justice in post-conflict societies. And rule number one we learned about in this course was that for any community to heal from a past trauma or collective suffering, there needs to be acknowledgement. If you look at South Africa or any country that went through conflict, or disaster, or war, rule number one is to acknowledge and come to terms with the past. And I saw that with Syrian children. Just acknowledging their suffering in a book, just telling them, “I see you” had an amazing therapeutic impact on them.

[F]or any community to heal from a past trauma or collective suffering, there needs to be acknowledgement.

When I came here to the UK, Lantana approached me and said, “We’ll do it in English.” Then I was really scared! This was created in Syria for Syrian kids. I was wondering if this was the right book for a country that was not at war. I thought, why would we want to expose children to these hard realities? I’m happy that my experience with reading the book taught me why we published it in the UK and the importance of it. I remember how after the first time I read it, with all its darkness, a girl came up to me and said, “The same thing happened to me because it was raining and I couldn’t go to the park!” So, children were relating in their own way.

Also, if we are too cautious about exposing kids to hard realities in children’s books, they’re going to suffer. They’re going to find out that real life is hard, and there are moments that are really dark, but they won’t have a point of reference to know how to deal with those big emotions and hard moments.

Whether the child has gone through war or not, dark moments in children’s books are really important because dark moments are a part of life. That’s what stories do for us—they help us learn and relate to hardship and understand how to come through difficult situations.

That’s what stories do for us—they help us learn and relate to hardship and understand how to come through difficult situations.

And in general terms these children know about war, they hear about it all the time in the news. They’re not excluded from what’s going on around them; they’re really clever. They deserve to know what’s going on with other children. I find it very sad to limit children, to deny them the truth about what the real world is all about.

Collaborative Classroom: By the way, in one of the illustrations in Tomorrow, when Yazan’s father goes out to bring him in, I noticed his father’s body is actually a building. How did you decide to do that?

Nadine Kaadan: I’m happy you mentioned this illustration; it’s interesting why I did it. In Damascus, you have a feeling that the city is a person, and now every time you see a destroyed building in the news, it’s like a part of you is destroyed.

There is also a feeling that you don’t want to leave—how do you leave a place that you’re so much a part of? But what if you get stuck in a city that’s not safe anymore? There is always this dilemma: do we leave or do we stay? There are so many emotions; this is how parents feel.

When the children ask me about that illustration, I ask them, “What do you see in it?” It’s beautiful that each one of them sees it differently, and that’s how it’s meant to be.

Collaborative Classroom: This video shows you reading with young people in many places; what have your interactions with children been like in Syria, England, Lebanon? How were the kids similar and how were they different?

Nadine Kaadan: Well, the first thing I learned from reading my book in so many different countries—and I’ve been lucky to travel a lot and to read the book in very different settings, from really posh schools in West London to a refugee camp where the basic needs of life aren’t even met—is that children are the same. They get excited about the same things. They love being heard. They relate to stories in beautiful ways.

The difference, I would say, is when I read my book at refugee camps (especially the ones that really have hardship in them), I learn a lot from the children. I see how beautiful their smiles are and their resilience is. They teach me about life and how to keep going and be strong, how to keep smiling and keep going to school even though the situation is very difficult. I go to the camps again and again because there I learn much more than I teach and I take much more than I give. I go and learn about life from them.

Collaborative Classroom: This touches on the theme you were talking about before, that children and people in these situations have so much agency, resilience, and strength; they have so much to teach us. Since we’re talking about kids, I wondered if you could talk a little bit about your childhood and home.

Nadine Kaadan: We moved to Syria when I was very young, so my childhood was mostly Syrian. But, of course, part of French culture came. (A lot of the books that I read when I was a child were French books.) I just knew when I was a child that I wanted to be a children’s book writer.

At ten, I started creating children’s books and magazines and selling them in school; I was very determined. That took up a big part of my childhood. I got a lot of support from my parents; my mom would photocopy the magazine for me, and I would fold them one-by-one and sell them in the school.

Art was a big part of my childhood, as well. I remember my mom would take me to the Fine Arts University and I would sit with the university students and learn how to draw. I was lucky to get a lot of support. The attention that I received when my mom realized that I loved drawing, writing, and illustrating is one thing that helped me do what I’m doing today.

Apart from that, it was just a normal childhood. Swimming classes and music classes were important, and going to the library was something that we used to do a lot. My mom was a French teacher so she would leave me at the library while she taught her class. I loved it; I don’t remember ever feeling bored during the hours I spent at the children’s library.

Collaborative Classroom: I know you said it was difficult to make the decision to leave Syria. But what was it like when you finally made that decision and left? I was curious how you selected London instead of France to settle in. It’s kind of a question about what home means to you.

Nadine Kaadan: Well, the war started around the time I was planning to go and do my Master’s. So, the plan was to go do that and come back. Even when I left, I was never planning to stay. I picked London because I love the universities here. I came here once when I was 21 after my graduation; I did a small course and made the decision that I wanted to study here rather than in France.

First I did a Master’s in illustration at Kingston University, and the war didn’t end. Then I did a Master’s in Art and Politics at Goldsmiths, and the war didn’t end. Then my husband followed me, and he did his Master’s at Oxford! Every year, we’d say “By the end of the Master’s, the war will be finished, and we’ll go back.”

I remember after five years, I was tired of living that in-between life, telling myself that we’d be back at the end of the year and then realizing “oh, no, we’re not going yet,” and then it being the same for another year. It was very unsettling. Finally I said, “That’s it. It looks like we’re just staying for a while now.” It’s the harsh reality.

Collaborative Classroom: What would surprise us to learn about you? It could be silly; it could be anything.

Nadine Kaadan: What would surprise you? Sometimes I find that getting my toddler to eat his vegetables is much harder than getting a book published. I think I’ve found that motherhood is even more challenging than getting published in an industry where diversity is a fight.

***

Interested in learning about other authors whose work is featured in our programs? Read an interview with author and illustrator Juana Martinez-Neal.