Scaffolding for reading independence involves empowering students to learn new skills by strategically building on previous experience and knowledge, gradually shifting ownership for learning from educator to student.

Effective scaffolding is a skill that should be in every educator’s toolkit. How do we do it well?

In a recent webinar, Collaborative Classroom’s Dr. Gina Fugnitto spoke with Dr. Taylar Wenzel and Dr. Analexis Kennedy, authors of the book Small Groups for Big Readers. This blog summarizes their top tips from the webinar about effective scaffolding for reading independence.

- How Teachers Can Prepare for Effective Scaffolding

- How to Scaffold Strategically Using Questions, Prompts, Cues, and Direct Explanations

- Questions as Scaffolding

- Prompts as Scaffolding

- Cues as Scaffolding

- Direct Explanation as Scaffolding

- Why Economy of Language Improves the Quality of Scaffolding

- Example of in-the-moment scaffolding using cueing, prompting, and using a correction routine for vowels

- How Collaborative Classroom Materials Support Scaffolding

- How Practice Helps Everyone Improve

- Author Bios

How Teachers Can Prepare for Effective Scaffolding

Intentional planning and practice prepares educators to be their most productive, helping to develop a deep understanding of the elements and nuances of lessons.

While it might feel forced or scripted at first, rehearsing lessons helps develop comfort and familiarity with the various scaffolding routines involved in the instruction. Educators might consider parameters such as:

- Where is it necessary to step in?

- Where is it appropriate to hold back?

- Where are the opportunities for strategic scaffolding and authentic literacy engagement for students within the lesson?

Pre-instruction rehearsal helps educators respond and engage naturally—and almost automatically—in the moment, contributing to efficiency and maximizing opportunities for student engagement.

Using routines offers predictability for the educator and for the students. When educators are clear on their role, clear on where they will be explicit and how they can be strategic, they ensure small-group time is productive.

Students benefit from practice time in a small-group setting, while educators offer deliberate, targeted feedback based on specific instructional goals.

How to Scaffold Strategically Using Questions, Prompts, Cues, and Direct Explanations

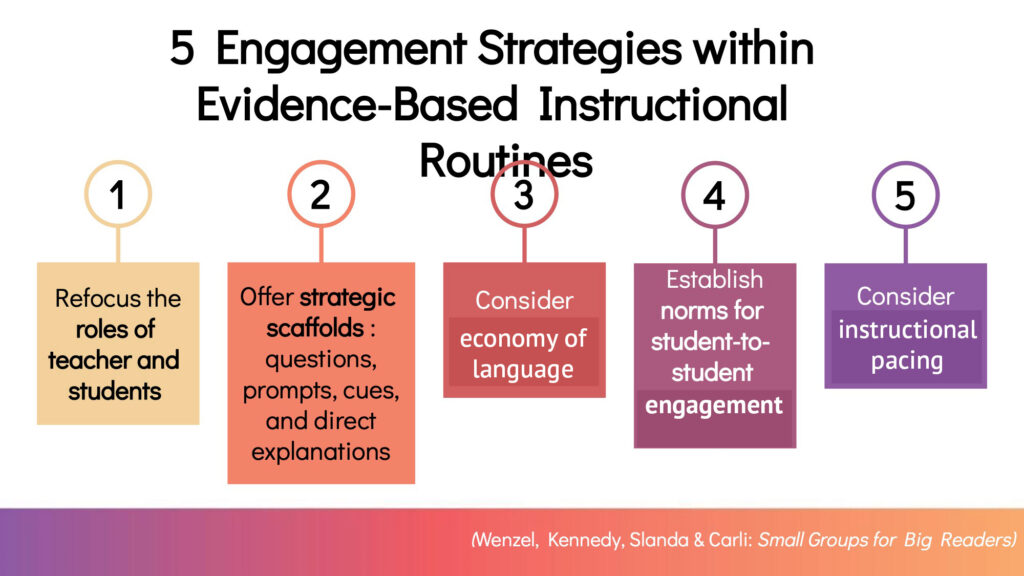

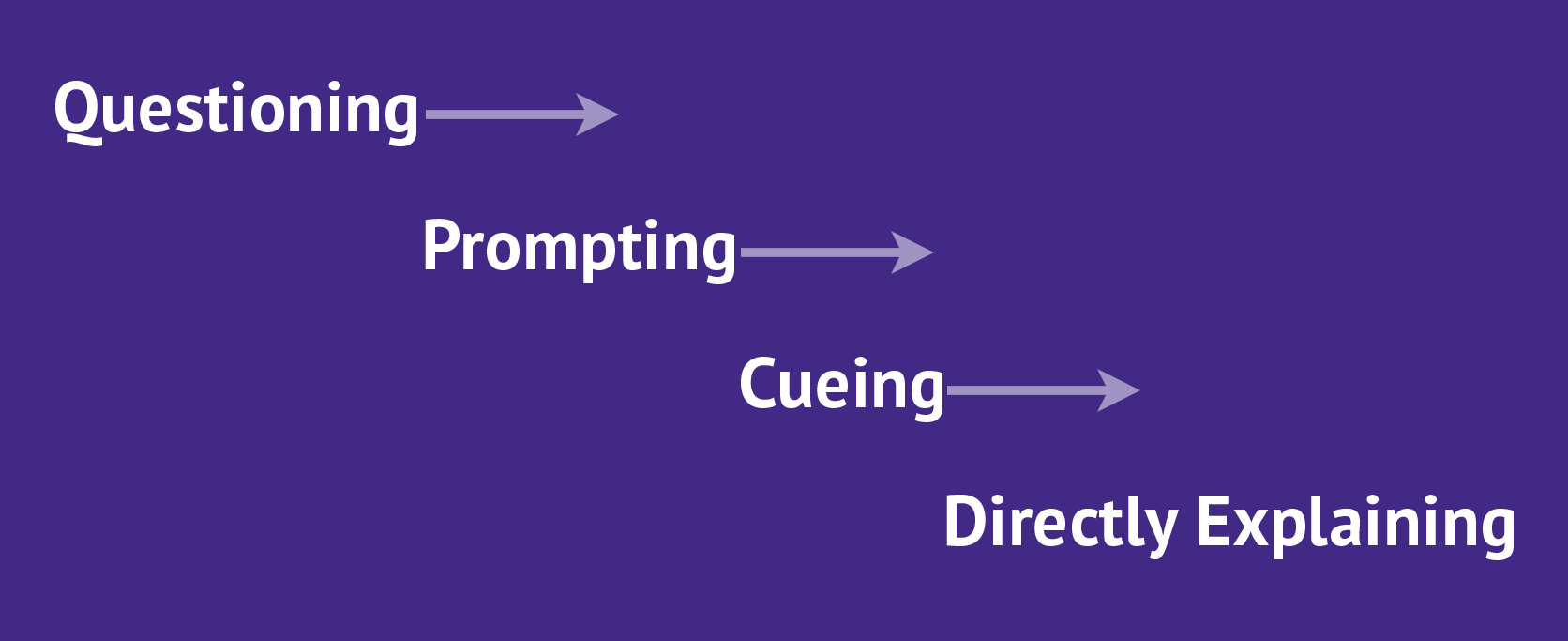

If the goal of small-group instruction is to move students toward becoming independent readers, it is critical to consider how questions, prompts, cues, and direct explanations are framed.

In most cases, educators will want to offer the scaffold that maximizes student ownership and engagement of the task. Most often, this will mean starting with a question and then offering a prompt, if needed, followed by a cue (if still needed).

An exception to this may be seen in explicit phonics instruction in which, rather than repeatedly offering different cues (after initially questioning and prompting), a teacher may choose to explicitly reteach a spelling-sound to help students accurately practice and apply the learning for the subsequent task.

What Is Meant by Questions, Prompts, Cues, and Direct Explanations?

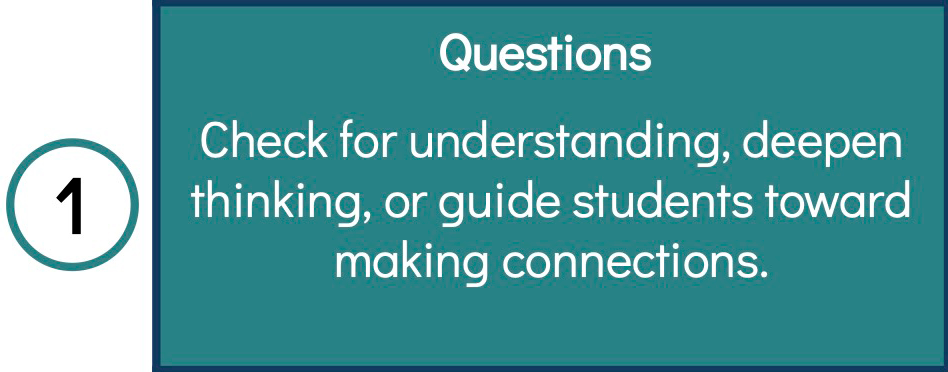

Questions as Scaffolding

Specific types of scaffolding questions check for understanding, deepen thinking, and guide students to make connections. These questions differ from content-based questions at the end of a lesson such as, “What was the girl’s name in the story?” or “Where did this take place?”

The types of scaffolding questions to focus on are those that support the thinking process and deepen a student’s understanding. This thinking process is a somewhat invisible practice that a more proficient reader or mature reader does unconsciously after learning.

Example in Action: Strategic Scaffolding Questions and Reading

Teacher poses a question to check for understanding. The intent is not to assess but to uncover misconceptions or errors to gauge if additional scaffolding is needed, or whether students are ready for less-supported applications of learning or more rigorous tasks.

After independent student reading of the text Sunny Days, Starry Nights:

Teacher: Why is it dark at night even when the sun is still shining?

Prompts as Scaffolding

The goal of a prompt is to help students make connections to something such as an applied skill that they previously learned, or to a strategy that they’ve been introduced to in the past.

One example is the open and closed syllable rule: Vowels have a short sound if closed by a consonant, and a long sound if open at the end (they “say their name”).

Prompting students by reminding them of that rule is a way to connect back to a strategy they’ve already practiced and can use again and again in different scenarios.

Example in Action: Strategic Scaffolding Prompts and Reading

Teacher poses a follow-up question to prompt students to do their own cognitive or metacognitive work.

Prompting questions may reference:

- Previous learning

- Background knowledge

- Known concepts, rules, or procedures

After independent student reading of the text Sunny Days, Starry Nights:

Teacher: Why is it dark at night even though the sun is still shining?

Student: The earth is going around the sun.

Teacher: You are right. Did you already know that before reading this text, or did you learn that from the author?

Student: I already knew it.

Teacher: What did you learn from the author in this text about why it is dark at night even when the sun is still shining?

(Prompt to use text evidence)

Cues as Scaffolding

Short of direct explanations, cues provide the most scaffolding support. Cues can be visual, verbal, or involve a gesture that helps the student form a relationship between the words on paper and a physical object or process.

One example is when an educator points to their head before the student reads: a way to signify “think” without saying the word. This type of visual cue helps move them toward independence.

Example in Action: Strategic Scaffold Cueing and Reading

A more direct approach used as a followup to questioning and or prompting.

Teacher shifts student attention to something they may have missed or overlooked. Cues may be gestural, verbal, physical, environmental, or positional. Cues may be taught in initial instruction so they can be effectively used as a scaffold without additional explanation for their use in the moment.

After independent student reading of the text Sunny Days, Starry Nights:

Teacher: Why is it dark at night even though the sun is still shining?

[Students offer text evidence that does not directly answer the question.]

Teacher: Turn to page 6. Use the text and the diagram on this page to find out why it is dark at night even when the sun is shining.

(Narrow focus on text excerpt and cue for attention to text and diagram)

Direct Explanation

Finally, a direct explanation provides clarity by defining the rule. For example, if students don’t understand the open and closed syllable rule, educators can elaborate by providing an illustration and explaining the rule again.

These everyday conversations help children feel a sense of belonging and safety—critical conditions for learning.

Example in Action: Strategic Scaffold Direct Explanation and Reading

Used as the most direct approach if prompting or cueing are unsuccessful—or, in the case of reading instruction, when explicit reteaching is needed to support a reading application task.

Teacher offers a direct explanation, which may include giving students the answer. Afterward, the teacher monitors student understanding by prompting them to explain in their own words and checking for their understanding.

After independent student reading of the text Sunny Days, Starry Nights:

[After providing the cue to look at the diagram on page 6, the student is still unable to explain why it is dark at night even when the sun is shining.]

Teacher: I am looking to answer the question about why it is dark at night even when the sun is shining.

In this diagram, I notice that the sun is shining on parts of the earth. I also see that other parts of the earth are not getting direct sunlight.

I’m now looking at the text to see if it can help me answer that question further. Oh yes, I see something that can help me here (reads sentence aloud and makes connection).

Why Economy of Language Improves the Quality of Scaffolding

Economy of language can be summed up quite succinctly: use as few words as possible!

Planning intentional questions, prompts, and cues and being prepared to provide direct explanations will support economy of language. Why is this important? Because using a lot of words or responding unintentionally interferes with the student developing their own voice as readers. Another result could be that the purpose of the lesson or specific task within an instructional routine becomes less—rather than more—clear for the reader.

The idea is to promote lesson continuity and return students to thinking about the task in front of them—their learning.

Sometimes it is tempting to simply provide the answer, or get into the habit of asking a lot of questions to promote a student’s thinking. For example, a student may produce an incorrect sound. The educator asks, “What’s another sound? Try again.” This can go on for several back-and-forth exchanges, unintentionally taking the student away from the lesson.

Instead, being deliberate and prepared through plenty of rehearsal regarding precise, concise language provides students with the opportunity to consider the questions, prompts, and cues in their own brain. Educators can be confident that their response in the moment is intentional and appropriate.

Here’s an example of in-the-moment scaffolding using cueing, prompting, and using a correction routine for vowels.

Using this rule: If the vowel is open, or comes at the end, it is long. If the vowel comes before the consonant, it is short.

The syllable is la and the student says /lā/.

Cueing:

The educator points to the syllable and asks, “Where is the vowel?”

The student responds, “It’s at the end.”

Prompting:

The educator asks, “Is the vowel long or short?” (Reminding them of the rule.)

The educator asks them to repeat the syllable, saying, “Again.”

Using a Correction Routine:

The educator says, “This syllable is /lā/.”.

In this example, the educator is saying as little as possible. The student is prompted to do the thinking while the educator starts with the least amount of support, knowing that if necessary, they can increase the support.

How Collaborative Classroom Materials Support Scaffolding

Curriculum can further strengthen how educators scaffold and support students.

During the webinar, Collaborative Classroom’s Dr. Gina Fugnitto provided insight into how SIPPS and Being a Reader Small-Group Reading provide instruction on foundational skills. Through very precise correction routines, the programs are designed to take the pressure off of educators. They can avoid checking themselves in the moment with questions like, ”Am I sure this is the kind of support that will help my students do their own thinking?”

The programs provide guidance on what to do as well as how to do it. They also providing a solid grounding in why it is done, eliminating doubt and promoting confident teaching.

Practice Helps Everyone Improve

While individual students are receiving scaffolding in the moment, learning and incorporating the teaching into their knowledge base, other students in the small group are also picking up on the concept.

They, too, are taking ownership, and getting the idea that while they are at the table doing the work, the teacher will be there to give them support if they get stuck.

A commonly used strategy, choral response, is another method that allows all students at the table to participate in the thinking process. Choral response also avoids isolating a single learner from getting extra practice or being called out for a particular reason. Everyone benefits from the added practice and thinking of choral response.

Conclusion

Scaffolding is a powerful technique educators use to empower students for reading independence. When done well, scaffolding helps students build new skills based on previous experience and knowledge. With practice, students internalize their lessons and gradually take responsibility for their own learning.

Highly effective scaffolding does not simply materialize in the moment. It requires deliberate planning and practice by educators before teaching a lesson. When educators prepare in an intentional way, increasing their their understanding of the elements and nuances of what they will be teaching, they gain skill and confidence in discerning when and how to employ the right scaffolding routine, at the right time.

Bios

Dr. Wenzel is a faculty member in the College of Education and Human Performance at the University of Central Florida, where she teaches undergraduate and graduate courses in elementary education.

As the Chief Implementation Officer at Collaborative Classroom, Dr. Gina Fugnitto leads the Implementation Department in advancing professional learning and fostering the conditions necessary for sustainable implementation success.

Dr. Kennedy is a lecturer of reading at the University of Central Florida. She spent 15 years working with K–12 students, teachers, and administrators as a classroom teacher, literacy coach, district reading specialist, and professional development coordinator.

Related:

How to Engage Readers During Small-Group Instruction

Why Sufficient, Deliberate Practice Is a Critical Element of Literacy Learning and Retention