Veteran educator Kathy King-Dickman models using student writing samples for assessing learning and planning next steps instructionally for a first-grade student — in this case, her granddaughter! She takes us step-by-step through her process.

Kathy King-Dickman is a Professional Learning Lead Consultant for Collaborative Classroom and has 30+ years of classroom experience in kindergarten through eighth grade.

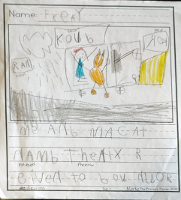

The writing sample below is a Mother’s Day card from my granddaughter Freya to her mother, sent during Freya’s first grade year. As a grandmother, this card warms my heart. As an educator, I find it just as valuable for use as an assessment of early literacy skills.

Figure 1: Writing sample (from the end of first grade)

Using the Writing Sample to Assess Learning

Taking a deeper look at this and other samples of Freya’s writing shows me what she has learned in her first-grade year.

So, what does this sample tell us about Freya’s learning?

- This sample shows that Freya has learned the high-frequency words I, love, you, so, for and me. I would need to assess several other recent writing samples to get a full list of other high-frequency words she knows.

- She has also learned much as a high-frequency word—or else she understands how to represent each sound in this word, which would show she has a solid understanding of the cvc pattern and the digraph ch.

- Her spelling of the word thank as thanc shows she understands yet another digraph. In seeing her correct spelling of mommy, I might do some exploring of other writing samples to see if she is solid on doubling a consonant at the end of a word when adding the suffix y, or if it has become a sight word for her.

- The period at the end of her two sentences tells me she is experimenting with end marks but does not have a complete understanding yet as she is missing the one at the end of the first sentence.

- In order to know if she has a good grasp on beginning sentences with capital letters, I would need to look at more samples of her writing; she might just be capitalizing the first letter as that is the correct spelling of the high-frequency word I.

More importantly than all the skills listed above, this sample tells me that Freya knows how to send a coherent message to an intended audience.

She also knows that note writing is a wonderful way to thank those we appreciate in our lives. Including the six hearts in this beautifully crafted piece shows that she understands illustrations must match what our words are saying.

She also knows that note writing is a wonderful way to thank those we appreciate in our lives. Including the six hearts in this beautifully crafted piece shows that she understands illustrations must match what our words are saying.

Using the Writing Sample to Plan Next Steps

This writing sample also guides me in understanding what Freya needs to learn next in order to continue moving forward in her literacy journey.

Possible next steps for Freya might include the following:

- We might want to focus on helping her learn to spell the high-frequency words thank, done, and have.

- We also might want to help her understand that we only capitalize proper nouns and first letters in a sentence, or we might choose to work with her on where sentences end and appropriate end marks to use.

- I would not work on the skill of adding details based on this sample alone, as this piece sufficiently meets its purpose: to thank and show appreciation for her mother. I would take a peek at other samples to see if her narratives include a beginning, middle, and end, her opinions have sufficient reasons with details, and her expository writing pieces contain several facts or one fact with supporting details.

How Do We Set Up Students for Success?

What learning should we prioritize for Freya? We would try to choose the skill Freya is closest to learning — not the ones that are too far from her zone of proximal development. This approach gives Freya a much better chance of success. We would not want to embark on teaching all that she needs to learn at once.

When we try to teach all that a child needs to learn, we have a high chance of overwhelming them and turning them off to writing. Brain research shows us that new skills are integrated into existing knowledge better when given in smaller rather than larger doses.

Brain research shows us that new skills are integrated into existing knowledge better when given in smaller rather than larger doses.

A word of caution: The sample above should be CELEBRATED upon receiving it. The teaching moment will come later, in the next few days during a one-on-one writing conference.

When a child writes spontaneously from their heart, there is only one acceptable response and that is to receive the piece with joy and gratitude. Even in the classroom, we must be careful to always celebrate our students’ writing first; teaching points are last but never least.

Another important aspect to consider when analyzing a student’s writing samples is growth. A way to take a serious look at growth is to have students write in notebooks from first grade on so that writing is saved and progress can be gauged. Kindergarten teachers should save or copy samples of writing from every unit in order to do this.

Growth: Comparing Freya’s Writing Samples Over Time

This next sample from Freya, taken approximately one and a half years prior to the first sample, shows her progress.

Figure 2: Writing sample from early Kindergarten

When we compare this earlier writing sample (Figure 2) with the one from May of her first grade year (Figure 1), we see Freya’s growth as a young writer. Here are some examples and observations:

- Freya no longer transposes the y and a at the end of her name as she did in this piece.

- Although she still transposes d for b and the other way around, samples show that she only does this now and then and she often asks for help deciding which is which. Reversals as shown in the label of ROK for car are no longer present in her writing. Other samples also reveal that although she doesn’t know the ai pattern for long a, she does understand the silent e rule for this skill.

- I would need to do some further checking to see if she has mastered the high-frequency word are in her present work. I have no writing to see if she has mastered adding ed to the end of a word as seen in namd from the earlier-age sample above; however, she does seem aware of this issue. On the phone last week she asked me, “Grandma, did you know that e-d can say ‘ed,’ ‘t,’ or ‘d’?”

- The spelling of her cat Phoenix as Thenix showed that at the time, Frey had a budding knowledge of digraphs but not a solidifying of sh, ch, th, or ph. Many recent writing samples prove she has since mastered them all.

- I have also seen ing used correctly in her recent work; whereas, a year ago the spelling of given for driving shows she used en’ to represent ing.

- Words that she was solid on in this earlier work were me and cat’; recent writing demonstrates she has control over several more sight words. All words in her earlier work demonstrate a budding knowledge of blending through the sounds of a word in order to approximate the spelling of that word; I know from observing her now that she is much more fluent and accurate at this crucial skill.

- The inclusion of only one detail in the piece could be due to the size of the paper or the teacher’s directions. I would need to see many more examples of writing to see if this was or still is an issue in her writing.

More importantly, Freya showed a strong knowledge that one can record the special moments of one’s life with the written word and that the illustrations must match the words on the page. The depiction of clouds and rain, the car, and especially an orange cat the same size as Freya shows her attention to detail. Phoenix is a fat cat!

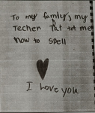

Now, let’s look at one more writing sample from Freya. The sample below is dated from almost two years prior to the first one in this blog (Figure 1). It demonstrates the dramatic progress children can make with solid instruction.

Figure 3: Pre-K writing sample

It is clear that from early on, Freya understood the power of the written word. Upon being asked to do a chore, she promptly sat down and wrote me this note. She has understood for a long time that the only way to escape a chore from grandma is to write or read. Write she did!

- This note shows she is experimenting with exclamation marks, and although she understands what they mean, she needs to learn where to put them.

- She shows early attempts at hearing the sounds in words and knows the high-frequency words I and to.

- This is where she most likely began to write en to represent ing.

What I most likely would have chosen to help her with two years ago would have been spaces between words.

Resources to Determine What Is Developmentally Appropriate

When I am looking at student writing samples, the following tools, available in the Being a Writer program, are very helpful for knowing what is developmentally appropriate at each age:

- Stages of Early Writing Development Chart. Found in the third edition’s Kindergarten and Grade 1 Implementation Handbooks, this chart provides information about several stages through which young writers commonly progress on their way to becoming conventional writers. The aspect I appreciate about this chart is that often a child is making marks on the page that seem at first just to be scribbles, but when we look at the Stages of Early Writing Development chart, it is clear that sometimes these marks are early attempts at approximated adult writing.

- Scope and Sequence Charts. The K–5 Writing Skills Scope and Sequence and the K–5 Grammar Skills and Conventions Scope and Sequence are both useful tools found in the Implementation Handbook.

- Conference Records. Found in the end of each unit’s Teacher’s Manual, the conference records offer valuable questions to ask yourself as you evaluate student writing.

The Being a Reader program is my go-to place for checking for foundational encoding skills or spelling—specifically, the Word Study and Small-Group Instruction Sets 1–12 sections of the K–2 Scope and Sequences chart found in the Being a Reader Implementation Handbook.

By listing the writing skills a child has control over and evaluating the child’s reading with the solid assessments found in SIPPS or Being a Reader, we can get a thorough picture of where a child is at and what needs to be taught next. In addition, assessing writing in this manner can support our decision-making in placing students in small-reading groups. This is using assessment for its most important purpose: planning intentional teaching based on individual, small groups, or even whole class needs.

Explore Being a Writer

Evidence-Based Writing Instruction for Grades K–5

Conclusion

I will close with a reminder that sometimes we just need to celebrate a piece of writing and save our teaching for later. I am reminded of my student Callie from many years back. After working hard to edit her final narrative for spelling errors, she added this dedication inside of her published book:

As much as I wanted to point out the spelling errors in her thanks to me for teaching her to spell, I knew I must stifle this urge. All that was needed at that moment was to share how impressed I was that she knew to add a dedication page and ask her to share it with our community of writers for those who might want to do the same.

I knew that there would be many opportunities to teach all that was needed developmentally for this budding little writer during our Being a Writer lessons, modeling of writing, one-on-one writing conferences, word work, guided spelling, and small-group reading lessons. At this point in the year, Callie saw herself as a capable writer. Every move I made as her teacher needed to continue to launch her as a growing writer. It takes much to get young students to put pencil to paper and little to stop the flow of those words.

Look for part two of this series, where I will analyze upper elementary writing samples as well as share how to take this information into our one-on-one writing conferences with students of all ages.

Related Reading

Read another blog by Kathy King-Dickman: The Joy of Watching My Granddaughters Move Through Ehri’s Word Reading Phases