With English learners now making up the fastest-growing segment of the K–12 student population, an increasing number of elementary teachers are feeling the impact, oftentimes reporting that they feel inadequately prepared to effectively meet the needs of language learners in their own classrooms.

With English learners now making up the fastest-growing segment of the K–12 student population, an increasing number of elementary teachers are feeling the impact, oftentimes reporting that they feel inadequately prepared to effectively meet the needs of language learners in their own classrooms.

Collaborative Classroom’s educative approach to curricula has always been a hallmark of our work, but as we set out to create the now-published second edition of the K–2 Being a Reader program, we knew that providing even greater support for teachers working with English learners had to be a priority.

To help us achieve this goal, we reached out to Dr. Marco Bravo, Associate Dean for the School of Education and Counseling Psychology at Santa Clara University. Dr. Bravo’s experiences as a researcher, as a teacher of courses in reading and language development at Santa Clara University, and as a writer of educative curricula himself were instrumental in helping us shape the Being a Reader English learner program supports. Subsequently, we were honored to have Dr. Bravo join the Collaborative Classroom Board of Trustees.

We recently had the pleasure of talking with Dr. Bravo about his experiences as well as the kinds of instructional strategies and scaffolds that are critical for English learners to gain access to academic content before they are able to speak English fluently.

Collaborative Classroom: You first came to Collaborative Classroom as an expert to help us shape the English learner support for our curricula; subsequently, you agreed to join our Board of Trustees. What was it about our mission or work that resonated with your own?

Marco Bravo: Collaborative Classroom’s pedagogy parallels my own beliefs about learning. At Santa Clara University where I teach, we talk a lot about cura personalis, which means “care for the whole person.” Collaborative Classroom’s curricula does this really well with a strong focus on academic development that’s infused with explicit teaching of social skills.

At Santa Clara University where I teach, we talk a lot about cura personalis, which means “care for the whole person.” Collaborative Classroom’s curricula does this really well…

That approach, taken together with Collaborative Classroom’s emphasis on recognizing that the culture, language, and experiences each child brings to their learning are assets to build on, is really conducive to language development for English learners.

Creating a safe environment in the classroom has the benefit of creating community and of allowing students to grow in these spaces, but as a language educator I’m thinking about how focusing on a supportive community that allows students to take risks creates opportunities for language development.

I also work as a teacher educator, and the professionalism with which Collaborative Classroom treats teachers was another draw for me. The organization puts teachers at the center of the education endeavor and recognizes that teachers know their students and their context best. The curriculum provides various opportunities for teachers to bend it to fit student needs instead of trying to bend students to fit the curriculum. That respect for teacher professionalism really attracted me to the organization.

[Collaborative Classroom] puts teachers at the center of the education endeavor and recognizes that teachers know their students and their context best.

Collaborative Classroom: You co-authored an article with Gina Cervetti and Jonna Kulikowich (2014) on the impact an educative curriculum can have on teachers’ use of instructional strategies when working with English learners.

You’ve also developed curricula yourself and advised the Being a Reader and Being a Writer developers on the kinds of features that are most supportive for teachers of English learners. Can you give us your perspective on what an educative curriculum is and how it differs from a more traditional program design?

Marco Bravo: An educative curriculum is designed to both support teachers’ enactment of a particular curriculum and to support their learning about the instruction itself as they teach. That’s a key distinction.

Using an educative curriculum is a form of professional development that, in essence, focuses on how to deliver the instruction. Educative materials provide information that helps teachers better understand the instructional choices the developers made. That information, in turn, can help teachers solve problems with implementation as they teach and make better decisions about how to modify instruction to fit the needs of their particular context and their students.

In a nutshell, a traditional curriculum is designed only for student learning, whereas educative materials are designed for teacher AND student learning.

In a nutshell, a traditional curriculum is designed only for student learning, whereas educative materials are designed for teacher AND student learning. These kinds of materials are especially critical for teachers of English learners, who often receive very little professional development that helps them address students’ needs, particularly when we recognize that these learners make up the fastest-growing sector of the K–12 student population.

I am by no means suggesting that educative materials can replace face-to-face professional development, but in the absence of those face-to-face opportunities, educative materials can begin to fill that development gap.

Collaborative Classroom: In your research, you found that some specific educative features led to increased use of suggested strategies as teachers enacted a curriculum. How did teachers interact with those features, and how did the features support teachers in embracing new strategies?

Marco Bravo: One thing I’ve noticed in my work is that it takes teachers some time to get used to a new curriculum given that they are initially learning both what to implement and how to implement it.

As such, it may not be until the second year that they begin to venture out and look at the other elements in the curriculum and start to think, “How do I differentiate for different types of learners? What kinds of assessments can I use? What suggestions do the curriculum developers have for me here?” As a colleague once said, “These educative features can ‘whisper in the ear’ of the teacher.”

Teachers with English learners in their classrooms especially appreciate finding that support right when they need it, in a feature that suggests “Here’s something you might want to do to better meet the needs of this particular student population.” This approach supports and respects the teacher as a professional in many ways.

Collaborative Classroom: In addition to your research, you’ve spent many years working with teachers at Santa Clara University, specifically teaching courses in reading and language development. How did your work with teachers inform the recommendations you made for some of the professional learning supports that were built into the Being a Reader program?

Marco Bravo: One key element I’ve learned from working in a teacher education program is that the teacher workforce is diverse. My work with preservice teachers in particular has helped me think about the different levels of support such a diverse workforce needs.

As novice teachers are preparing to teach in their first classroom, they are having to learn about curriculum while also navigating classroom management, assessment, and individualizing instruction for students. These teachers are likely to need much more support in implementing a curriculum than seasoned teachers.

Support for a teacher enacting a language arts curriculum for the first time might look quite different from that needed by more experienced teachers who already have a strong sense of how to manage their classrooms and more readily know what types of supports students are likely to need.

Thinking about that diversity of teachers has caused me to think about educative notes in new ways. For example, we need to be very careful about using acronyms, recognizing that while many teachers may know and understand them, acronyms are a language that can make it difficult for novice teachers to understand what’s being said.

In similar ways, my students have taught me a lot about the diversity of their own students, helping me keep in mind that the English learner population is very diverse.

A student-teacher once shared a story about an influx of Russian immigrants to her school community, resulting in an immediate need for Russian interpreters. Fortunately, she spoke Russian herself and was able to assist, but her experience reminded me that just as we have this diversity in the teacher workforce, we also have a diversity of English learners in the classroom.

Teachers come to us with various levels of English proficiency, different levels of educational experiences, different anxieties towards learning a second language, and different abilities in their reading and writing as well. So in my work with the Being a Reader program developers at Collaborative Classroom, I knew that the educative features needed to acknowledge this diversity and support teachers with different levels of knowledge and experience.

Collaborative Classroom: It seems that with the rapidly rising number of English learners in US classrooms, particularly in states not accustomed to serving them, all teachers will likely have English learners in their classrooms and will require support in addressing their needs.

In your research, you’ve found substantial evidence that many elementary teachers feel inadequately prepared to work effectively with language learners. What advice might you offer teachers who are in that situation? What are the most important considerations to keep in mind?

Marco Bravo: Dr. Aída Walqui, a researcher working out of WestEd, has a great mantra when referring to work with English learners: “Amplify, don’t simplify.” Design instruction that is high quality, challenging, and supportive of learning opportunities for English learners and other students who need language support.

Too often the initial response of teachers working with English learners has been to “water down” the curriculum to make it easier for them. But this works counter to what they really need.

Too often the initial response of teachers working with English learners has been to “water down” the curriculum to make it easier for them. But this works counter to what they really need. If your students are third graders and you’re giving them second-grade material, this means that they won’t have access to the grade-level curriculum and they will fall further and further behind.

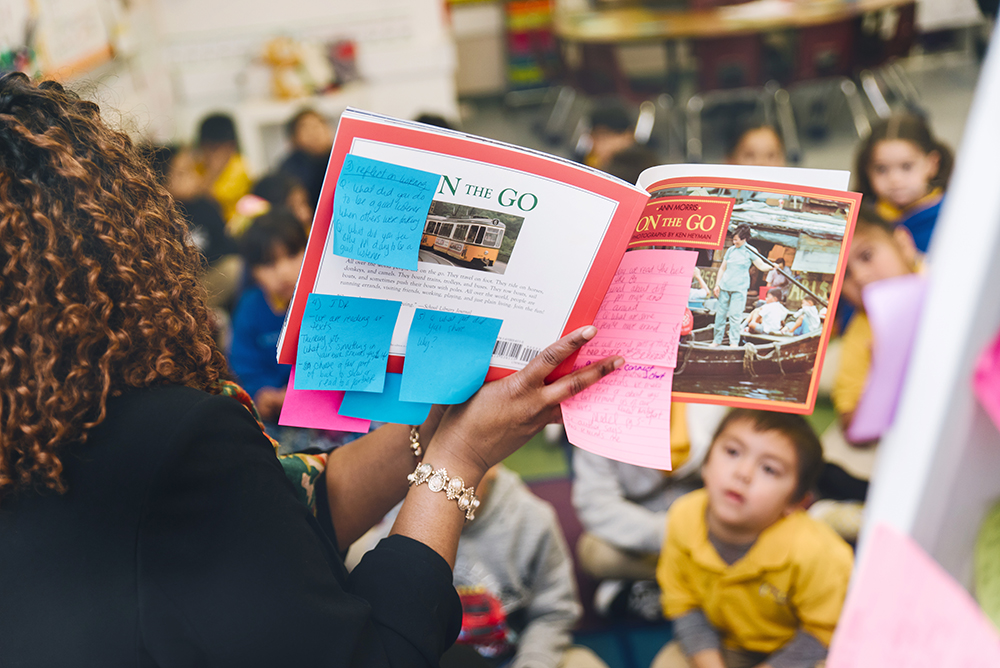

Instead, we should amplify the grade-level curriculum for English learners through a lot of scaffolding and support, using visual representations, providing additional time for them to process information, and leveraging the students’ native languages. These are just some of the adaptations that are infused into the Being a Reader program.

Get Being a Reader Sample Lessons

Download sample lessons, placement assessments, and the Being a Reader program preview.

What makes school experiences difficult for students, especially for those with beginning and early intermediate levels of English proficiency, is that it’s often the abstract concepts and ideas that trip them up, concepts that could easily be made more concrete through a different series of examples.

One text I reviewed had something to do with the motion of Earth, of rotation and orbit—two very complex and abstract concepts about how the Earth is both turning and moving around the sun at the same time. But illustrating it through a model could bring English learners into that conversation much sooner and make the learning much more accessible.

Without these kinds of scaffolds, you’re more likely to lose your English learners. But if we create some kind of visual or model of the learning, we integrate them into the learning opportunity and keep them with us.

Another mantra that I’ve seen well-represented in the Collaborative Classroom materials is “think differences, not deficits.” My hope for my students is that these future teachers will take an asset-based pedagogical approach to their teaching philosophy and view the cultural and language diversity that students bring to the classroom as added value that actually strengthens the classroom community and, ultimately, the society at large. The Collaborative Classroom materials respect and support these ideas.

Think differences, not deficits. My hope for my students is that these future teachers will take an asset-based pedagogical approach to their teaching philosophy and view the cultural and language diversity that students bring to the classroom as added value that actually strengthens the classroom community…

Collaborative Classroom: Can you give some examples of how you might use an asset-based approach to bring those differences into the classroom as you’re building the classroom community?

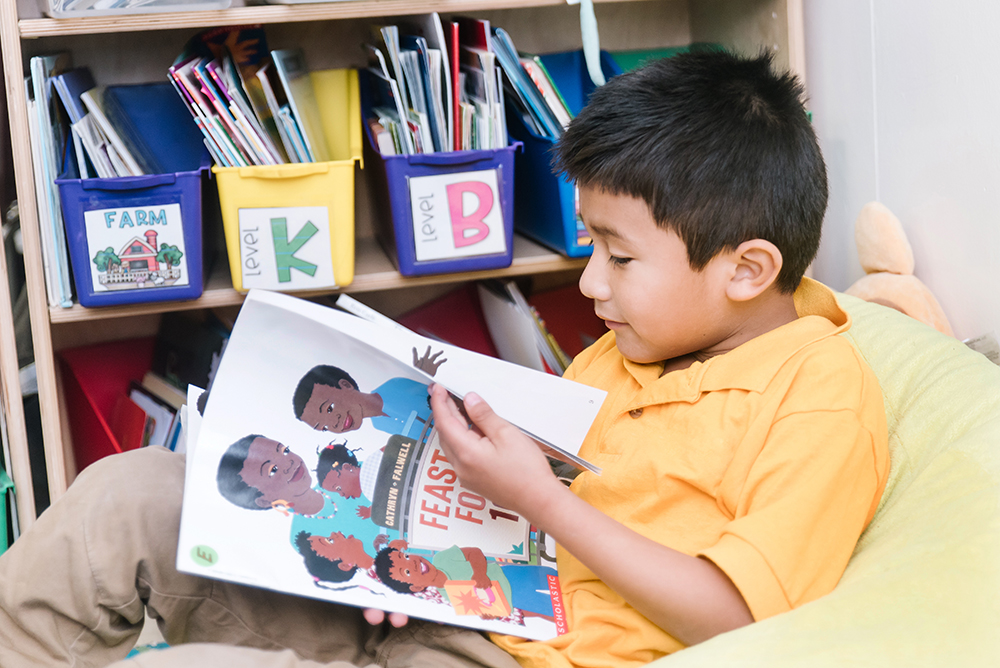

Marco Bravo: Diversifying the literature that students are exposed to—making sure there is multicultural literature infused into the curriculum and what students are reading—is essential.

But more than that, it’s about probing students to learn about and draw from their experiences, thinking about what Luis Moll refers to as the “Funds of Knowledge” that students bring with them to the classroom. How do we think about approaches that can help us encourage students to share these experiences?

I’ve worked with students who are very well versed in reading different kinds of texts than what is traditionally expected of them. For example, they may not have had the experience of having a family member read to them at bedtime, but even as early as second grade, they could read a bus map, use the color-coding, and know where to get on and off, because those were the kinds of literacy experiences they lived.

These different kinds of literacy experiences from their community can be tapped into and extended to help them build the kinds of school literacies that are expected of them.

Collaborative Classroom: Is there anything else you’d like to share about what’s truly important in the support we provide for English learners?

Marco Bravo: It’s important to stress that the scaffolds and strategies we’ve discussed are critical for English learners.

When talking about these practices, I often hear educators say, “Well, that’s just really good teaching that would be good for all of our kids.” And while that’s certainly true for many of these strategies, the one difference is that if a native English speaker does not get these scaffolds from the teacher, that student will probably find another way to access the material. In contrast, for English learners, these scaffolds are essential. If we don’t provide the support they need, it makes it really difficult for them to catch up.

For English learners, these scaffolds are essential. If we don’t provide the support they need, it makes it really difficult for them to catch up.

For example, you generally don’t have to explain common idiomatic expressions to most native speakers of English. Those students have access to language that can help them figure out idioms. But explaining those idiomatic expressions would be a modification you would absolutely want to make for an English learner. So, by centering English learners in this conversation and acknowledging how critical these scaffolds are for them, we can ensure that they gain access to the same academic content as their native-speaker classmates.

It’s also important to consider the role of a safe classroom community in supporting English learners. That is something I noticed about the Being a Reader curriculum: the writers went above and beyond the [standard] recommendations for building a safe classroom community.

We know that for English learners, anxiety or other affective variables often play a role in whether they are willing to take a risk with language. The kind of classroom community that’s inherent in the Being a Reader curriculum provides space for students to take those risks, to feel that it’s okay to try out the language, knowing that even though they might be incorrect, they won’t be ridiculed. There is a lot of evidence that in these environments, language learning happens much more fluidly.

Additionally, when we take that asset-based approach we discussed earlier to draw on student experiences, students feel honored, respected, and that they are an important part of the community.

REFERENCES

Cervetti, G., Kulikowich, J., & Bravo, M. (2014). The effects of educative curriculum materials on teachers’ use of instructional strategies for English language learners in science and on student learning.

Contemporary Educational Psychology, 40, 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2014.10.005

***

Related reading:

What Is An Educative Curriculum?

A Conversation About Instructional Equity with Collaborative Classroom Board Member Zaretta Hammond

Explore Being a Reader

A comprehensive K–5 reading program, Being a Reader™ is the first of its kind to integrate foundational skills instruction, practice in reading comprehension strategies, and rich literacy experiences with explicit social skills instruction and activities that foster students’ growth as responsible, caring, and collaborative people.