Children’s books are the cornerstone of Collaborative Classroom’s programs; in a way, the authors are our behind-the-scenes collaborators. We want teachers, administrators, students, and parents to be able to learn more about these wonderful authors and illustrators. We are happy to present the next in our series of interviews, a conversation with author Ken Mochizuki. His book Baseball Saved Us (winner of a Parents’ Choice Award) is part of our Making Meaning program; A Passage to Freedom (an American Bookseller Pick of the Lists) is part of our AfterSchool KidzLit program; and Heroes (ILA Teacher’s Choice) is included in our Comprehension Strategies Library.

Collaborative Classroom: How did you decide to write your first book, Baseball Saved Us?

Ken Mochizuki: Out of nowhere, I received a phone call from Philip Lee in the summer of 1991. He told me he had gotten my name from his wife, Karen Chinn, whom I had known when she lived in Seattle. Philip was canvassing the country for writers and illustrators for his first line of children’s picture books with his newly formed publishing company, Lee & Low Books in New York. I hadn’t considered writing in the children’s literature field at the time; however, I was open to the possibility.

Philip sent me a magazine article about Japanese Americans playing baseball in the American camps in which they were forcibly confined during World War II. I created my historical fiction story based on that article. At the time, I worked for an Asian-American community newspaper in Seattle. Ever since redress occurred in 1988, when the U.S. government acknowledged that the forced confinement of Japanese Americans during World War II had been a mistake, I had been researching and covering the subject-writing newspaper articles. Therefore, I had done most of my research before Philip pitched his proposal. I had been paid to do my research for Baseball Saved Us, although I didn’t know it at the time. Talk about serendipity!

Collaborative Classroom: You mentioned that working as a journalist, you learned to use the least amount of words to say the most. That skill helped [you] immensely in writing books for young readers.

Can you describe your process for selecting the best language to convey your meaning, for rewriting, and, presumably, cutting? What advice do you have for students learning to write their stories?

Ken Mochizuki: When I do presentations for students, I talk about how when I was their age in school, the teacher gave us a list of 10 words each week. At the end of the week, we were tested on the spellings and definitions of the words.

I ask the students if they receive similar assignments. “Take those seriously, now,” I tell them. “Your teacher isn’t doing it just to give her something to grade. Vocabulary becomes very important when you are an adult!” I add that “the action is in the verb, literally!” Knowing the right verb to use in order to convey a specific experience to your reader is critical.

I once heard an author say, “If I had my way, I’d eliminate all adverbs. Adjectives would be next.” I think adjectives still have a use, but I agree with what he said about adverbs—a sentence should be descriptive enough so an adverb isn’t necessary. As for rewriting: I never have a problem finding enough words; I have to cut pieces down. That is usually the hard part. What goes? What stays? I was taught, literally and through analogy, that less is more.

Collaborative Classroom: Both you and Christopher Paul Curtis (whom I recently interviewed) wish you’d been more interested in your grandparents’ stories, and regret the loss of family history that you might have absorbed if you’d listened at the time. In your own ways, you’ve both made history accessible and interesting to young people through your books. Could you talk about the importance of family history to our understanding of ourselves and of the wider world?

Ken Mochizuki: As the saying goes: How do we know where we’re going, if we don’t know where we’ve been? For me, learning my grandparents’ stories was practically impossible, since they spoke mostly Japanese and I didn’t understand any of the language. If they shared their past, my brothers and I received very abbreviated translations from my parents, who in turn hardly ever talked about their own stories. Only within the last few years, with the prompting of Internet genealogy services, have we started to piece together my family history.

I used to tell students that my paternal grandfather was the first of my family to immigrate to the U.S., in 1907, but one of my brothers recently uncovered that our other grandfather was actually the first to arrive in the U.S., in 1905. I think it’s important to know one’s family story and to be able to trace it as far back as possible. In this way, one will have an understanding of his or her family members, of what was going on in the world during their time, and of how they fit into history.

For our young people, this information provides self-knowledge. Knowledge of self results in self-pride! This is especially important for members of ethnic groups considered “foreigners,” who are thought to be recent immigrants. A family history could prove that one’s family has been a part of America for a long time.

I think it’s important to know one’s family story and to be able to trace it as far back as possible. In this way, one will have an understanding of his or her family members, of what was going on in the world during their time, and of how they fit into history.

Collaborative Classroom: Is there a historical story that you would really love to tell, but haven’t yet been able to share?

Ken Mochizuki: Thirty-three thousand Japanese Americans served in the U.S. armed forces during and shortly after World War II. The most famous was the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the all-Japanese-American segregated unit that became the most decorated American combat unit for its size and length of service (about three years). Within the 442nd was the 100th Infantry Battalion, the forerunner of the 442nd, composed of Japanese Americans mostly from Hawaii. In combat before the rest of the 442nd, it became known as the “Purple Heart Battalion” for suffering heavy casualties and showing heroism fighting the Germans in Italy.

In October 1944, the 442nd was assigned to liberate towns in northeastern France. While the 442nd engaged in treacherous, bitter house-to-house fighting in the town of Bruyeres, the 100th was assigned to liberate the nearby town of Biffontaine.Company B of the 100th became pinned down within the buildings of Biffontaine when a larger German unit surrounded it. With the Americans returning less and less fire from their guns, the Germans knew Company B was running low on ammunition.”Do you surrender?” a German commander yelled out in English. “Go to hell!” Company B’s commander shouted back.

Luckily—and to this day, nobody can recall how—members of Company B stumbled across a cache of German guns and ammunition. Equipped with the enemy weapons, the 100th Battalion’s Company B beat back the Germans, forcing them to withdraw, and Company B liberated the town. I consider this battle and heroic stand on par with the siege of the Alamo. Yet, how many know this story?

Collaborative Classroom: Part of our mission is to support teachers in creating a classroom environment where all students can thrive and learn from one another. The most significant way we do this is by providing teaching materials that blend academic with social skills development: these materials are grounded in diverse children’s literature of which your books are a part.

In fact, Baseball Saved Us is in over 6,000 classrooms with our Making Meaning program, and Passage to Freedom is in over 4,000 sites with our AfterSchool KidzLit program. What do you think about the way your books are employed in classrooms and after-school programs that use our curricula?

Ken Mochizuki: That so many copies of the books are in classrooms is quite encouraging. I’ve received letters-usually accompanied by drawings of scenes in Baseball Saved Us-from elementary school students from all over the country. Of significance is that I have not seen one drawing in which the characters are drawn stereotypically, such as with “slanted” eyes. Why? Because none of the characters are drawn that way in the book, thanks to the great illustrator Dom Lee.

Also, the book includes the word “Jap.” Use of that derogatory term has sometimes created controversy. A school district in Connecticut pulled the book from its second-grade reading list. In other places throughout the United States, teachers and school librarians have initiated discussions with students from pre-K on up about what that word means. It is good to know similar discussions could be taking place in over 6,000 classrooms, thanks to Collaborative Classroom.

In today’s political climate, schools could use more picture books about Muslims or Latino immigrants.I was once a presenter at an educators’ conference in Omaha, Nebraska. The conference organizer told me that a district official—maybe even the district superintendent—had remarked about Passage to Freedom, “I didn’t know the Japanese did anything good during World War II.” Were all Germans Nazis? There were obviously Japanese citizens who protested the actions of their warmongering military dictatorship during World War II. As with any dictatorship, those who did object ended up dead, in prison, or in exile.

I’m glad that through Passage to Freedom many students will see that not all Japanese in wartime Japan were fanatically (stereotypically) loyal to the Emperor; that Consul Sugihara, the heroic diplomat of the story, was Greek Orthodox (not Buddhist, as is often assumed); and that he considered his wife an equal and consulted her on all his important decisions (he was not the stereotypical Japanese male chauvinist).

One of my “gurus” is the late historian and scholar Dr. Ronald Takaki, whose 1993 book, A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America, was another major influence on my choice of writing topics. In his unique approach to our country’s history, Dr. Takaki examines how different American ethnic groups have often intersected for a common good. He cites how Jewish Americans assisted African Americans in their struggle for civil rights. Jewish Americans joined John Brown in his failed abolitionist insurrection prior to the Civil War; and again, over 100 years later on the first day of Freedom Summer in Mississippi, three civil rights workers were murdered-one African American and two Jewish Americans.

As Dr. Takaki once said, We better start learning about each other, or we’re on the road to Bosnia.

Bosnia was the world’s flash point for ethnic strife during the early ’90s; today that might be the Middle East.

Collaborative Classroom: You’ve presented at a lot of schools throughout the country. What is your favorite part of those visits? What have you noticed about the influence of technology in the classroom? Could you provide examples of the ways in which students have changed and the ways they have remained the same over the years?

Ken Mochizuki: My favorite part of those visits is interacting with students who are prepared, motivated, and engaged. When I encounter such students, I also rise to the occasion. I am sometimes amazed at the very adult questions they pose. A student in a fifth-grade class once asked me, What is a major regret you’ve had in your life?

(Say what?! My answer-and I’m surprised I thought of it quickly-was that I didn’t take college as seriously as I should have.)

Conversely, my least favorite part of school visits is when the students are undisciplined and I become a clock-watcher, like a basketball player with the ball trying to run out the clock to win the game. That has not changed—there will always be schools with those kinds of problems. Students now-even at elementary schools-are so tech savvy! They definitely know a lot more than most adults do. Young people can also complete their schoolwork more quickly due to the ease of Internet research. Along with their technical savvy, a difference in students I have observed over the years is an increasing intelligence and sophistication beginning at younger and younger ages, witnessed by the questions students sometimes ask (as cited above). What they know about, I never would have known at their ages!

What remains the same is encountering the occasional exemplary student. As I was in the process of a 2002 school tour throughout southern Idaho, I visited the town of Malta, Idaho, with a population of about 300. There, when I was asked why the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, a third-grader began explaining all about the embargoes Western powers had enforced on Japan, leading to war. Wow! A third-grader?

Collaborative Classroom: You have described your high school as being fairly diverse (one-third Asian American, one-third African American, one-third white) and said that you received your multicultural education every day by just attending school.

Can you talk about some defining moments in high school and in elementary school?

Ken Mochizuki: Not being able to recollect any “moments,” I would have to say the fact that there were no defining moments was a defining moment. Sure, “race” still mattered when I reached junior high (seventh through ninth grades) and high school, as exemplified by the African-American students sitting together in the school cafeteria and the whites mostly sitting at one table and the Asian-American students at another. However, for the most part, we knew fellow students more by an attribute rather than ethnicity, e.g., the great athlete, the 4.0 student, the one with the cool car.

Collaborative Classroom: In A Passage to Freedom, you write movingly and knowledgeably about individual acts of heroism that require difficult moral decisions. Was there a time you had to make a decision to break the rules or make yourself vulnerable in order to help an individual or a group of people? Has anyone ever done that for you?

Ken Mochizuki: Being involved in student government during high school, I and other students often had run-ins with our vice principal-a myopic, zero-personality disciplinarian who enforced “no hanky-panky” rules within the halls and hangouts. One day, he suspended a friend of mine from school, and then made up the reason for it after the suspension. Was it just a power trip? Did he just dislike that particular student? I never knew. A few of us went to bat for our friend, taking on the school administration much to the disapproval of my parents, other parents, and fellow students.

My suspended friend returned to school and, around that same time, I began advocating for books and other information on Asian-American history in the library, of which there was nil. This action was also met with raised eyebrows, for I was “rocking the boat.” Since these events took place toward the end of my senior year, I never learned if my efforts had any long-term effect at the school. I fictionalized this experience in my young-adult novel, Beacon Hill Boys. A prominent theme in the story is, as the protagonist’s father says, “The nail that sticks up the highest gets hit the hardest!”![]()

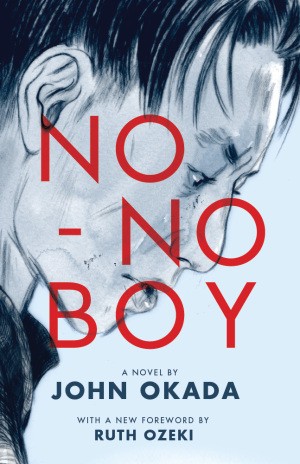

Collaborative Classroom: John Okada‘s No-No Boy set you on your course as a writer. It is a fiercely honest, intelligent, and moving story of a man struggling mightily to come to terms with his identity.

Okada explores forgiveness and acceptance, or the lack thereof: The main character, Ichiro, realizes the “great compassionate stream” that is America, and this realization makes the fact of the Japanese concentration camps all the more unfathomable. He glimpsed the real nature of the country against which he had almost fully turned his back, and saw that its mistake was no less unforgivable than his own.

Could you talk about what you see as the central struggle in this story and the influence this book had on your life?

Ken Mochizuki: Being Japanese American, the protagonist Ichiro not only has to deal with post-World War II American racism, but he also has to deal with another strike against him: the fact that he chose to be a “No-No Boy,” answering “no” to two questions on a loyalty questionnaire—thus refusing to volunteer for the U.S. Army as a protest over being imprisoned in an American camp during the war.

Therefore, he is an outcast-particularly among the war veterans-within his own Japanese-American community, and even with members of his own family. How does he cope with not being accepted anywhere he goes or turns? Luckily, he becomes connected with a few, and rare, fellow Japanese Americans who disregard his past.

How does he cope with not being accepted anywhere he goes or turns? Luckily, he becomes connected with a few, and rare, fellow Japanese Americans who disregard his past.

One of the loveliest scenes in the book takes place when Ichiro and his friend, Emi, stop by a roadside dance hall. While they dance, a white stranger, for unknown reasons, buys them both a drink—a surprising occurrence and the complete opposite of what both the characters and the reader expect.This novel was first published in the mid-’50s and was considered a commercial flop, but was then resurrected to acclaim in the mid-’70s.

One of the reasons it so spoke to me in my early 20s was because it was set in Seattle. Since I grew up there, I knew the locations where Okada set his scenes, and I could vividly see the Seattle sights. In fact, I have since located the site where Ichiro’s fictional family store would have been.Secondly, No-No Boy proved to me that we-Americans of Japanese descent-have our own stories to tell and, most importantly, that we could write them!

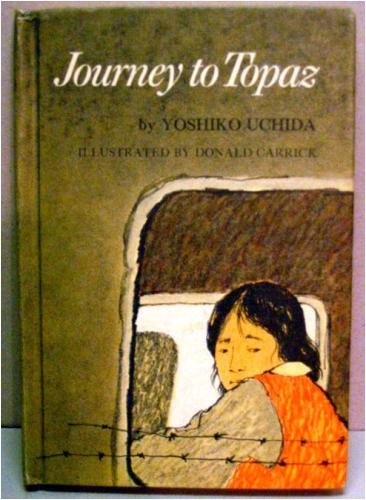

Collaborative Classroom: You graciously thank Yoshiko Uchida (author of Journey to Topaz, The Bracelet, Desert Exile, and many other books) for paving your way as a writer: she wrote children’s books about Japanese subjects in the decades following World War II-a particularly lonely and charged time to do so-and beyond. Did you read her books growing up? Are there children’s book authors writing now who you think are similarly paving the way for other future writers?

Ken Mochizuki: No, I didn’t read her books as a youngster. I wish I had, for if I’d known some of my own background, I might have had a different view of myself. As I said before, knowledge of one’s own history can equal pride in it. I read her books while struggling to become a writer. Like John Okada, she was an inspiration and further proof that we had our own stories to write.

As for other inspirations—those who had the guts to go there—here are my Big Three:

- Judy Blume, for having the courage to tackle sensitive, controversial topics of the time, and also for making the subject matter appropriate for young readers. That she is still one of the most censored authors in America I consider to be a badge of honor.

- Walter Dean Myers, for making gritty inner-city subjects palatable for young readers. When I was writing my young adult novel, Beacon Hill Boys, early drafts were full of four-letter words, since I wanted to capture how teenagers authentically talked. My agent advised,

Read Walter Dean Myers.

And, sure enough, a character never spoke a four-letter word, although the implication was there, as if the words actually existed in the dialogue. - Laurence Yep, who could seemingly turn any complicated, and often scientific, subject matter into folklore.

That’s the value of fiction-it can sometimes prepare you for what happens in life.

Collaborative Classroom: Speaking of gratitude for those who help us on our way, did you have a favorite elementary school teacher you could tell us about?

Ken Mochizuki: I like to share this favorite moment I had with one of my elementary school teachers: Jimmie Connor, our fourth-grade teacher, was reading Charlotte’s Web to the class. During the morning of November 22, 1963, she read the chapter in which Charlotte the spider died.

Of course, a collective sigh of sadness emitted from the entire class. My father sometimes picked my older brother and me up for lunch, since we didn’t live far away from school, and when we left our school portable-our school was all portables—we noticed the American flag was at half-mast. We asked our father why and he replied that President Kennedy had been shot.

When we arrived home, we saw the news on our black-and-white TV (all TVs were black-and-white then) that our president was dead. When I returned to my class, my classmates were abuzz about the assassination, and I told my teacher that both Charlotte the spider and our president dying on the same day was difficult to accept.

And her profound reply was: “That’s the value of fiction—it can sometimes prepare you for what happens in life.” To this day, I remember that moment.