“Once children see themselves represented in books, their existence is validated, and they feel that they are part of the world.”

All children need to see themselves and their peers in the stories shared and discussed at school. Kids of color need diverse books because so often they do not see themselves in literature, and therefore feel marginalized, even invisible. White kids need diverse books because they see too much of themselves in literature and this may lead them to feel that they are the center of the world. As Nancy Larrick said 50 years ago in her article in The Saturday Review, and which, sadly, still resonates: Although his light skin makes him one of the world’s minorities, the white child learns from his books that he is the kingfish.

Our developers have always tried to select books that fit the instructional needs of the program and fit the urgent social need for diverse books in the classroom. In my last blog, I talked about the importance of checking the results of our good intentions. The CCC Diversity Review Book Project was born out of a desire to find out if we had in fact been inclusive in our book selection-specifically, by analyzing the literature used in our Collaborative Literacy suite of programs. Collecting data about those books would enable us to speak and write knowledgeably about the range of literature we are actually putting into the classroom and understand the messages it sends to students.

“Without data you’re just another person with an opinion.”

For this endeavor, it made sense to get outside help from someone knowledgeable about data collection and analysis. Jill Casey agreed to consult, and fortunately for us, she also had experience with social justice projects through her work for jdcPartnerships.

With Jill on board, we created an interdepartmental review team of about a dozen folks from customer service, editorial, marketing, program development, Learning Technologies, and publisher relations. This team helped refine the type of data we’d collect and determine how we’d collect it, and then conducted the actual review of the 354 books. The first time the team got together we shared why we wanted to do this project by talking about the role that books played in our lives. These were meaningful conversations that reinforced the relevance of this review. From the get-go, people were engaged, with everyone contributing ideas and energy. To determine what data to collect, we studied the Cooperative Children’s Book Center’s (CCBC) annual review of children’s literature, consulted with Lee & Low Books (a leading publisher of multicultural literature and a vocal advocate for diversity in publishing), and read 10 Quick Ways To Analyze Children’s Books for Sexism and Racism from the Council on Interracial Books for Children.

To determine what data to collect, we studied the Cooperative Children’s Book Center’s (CCBC) annual review of children’s literature, consulted with Lee & Low Books (a leading publisher of multicultural literature and a vocal advocate for diversity in publishing), and read 10 Quick Ways To Analyze Children’s Books for Sexism and Racism from the Council on Interracial Books for Children.

We decided to analyze each of our books by focusing on the following main categories:

- Gender and race of the author and illustrator

- Gender and race of the main character or a major secondary character (for books about humans)

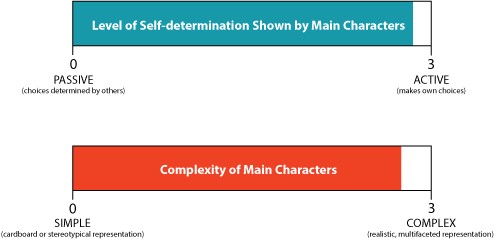

- The complexity of those characters

- The visual representation of those characters

- The book’s setting

- Family structure

We tried to select categories that could be determined as objectively as possible. We knew that was impossible to do completely, which is one more reason it was important that the review team bring a variety of perspectives to the table.

For a few busy months we checked out books from an impromptu lending library and struggled with making evaluation decisions. Sometimes, analyzing images posed a particular challenge: Why is the black boy talking to the police officer? But the boy looks at ease, and the officer is a friendly-looking woman. We talked in the office kitchen about books we loved or didn’t, and how to determine the setting or the main character. We also talked about the push to get all the books reviewed by our deadline and wondered about what the results of our study would tell us. We knew that the probability of having achieved perfect inclusiveness across our book selection was unlikely given the context within which our developers worked: While 37% of the U.S. population-and about 50% of K-12 students in the U.S.-are members of a racial minority, only about 10% of children’s books published in 1994-2014 and reviewed by the CCBC were by or about people of color.

Here are our key findings about the children’s books in the Collaborative Literacy suite:

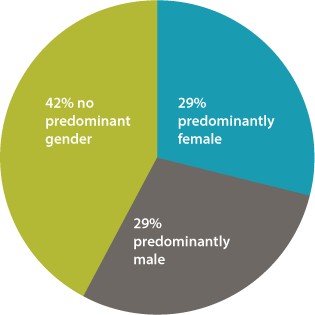

- They are about male and female characters in equal measure.

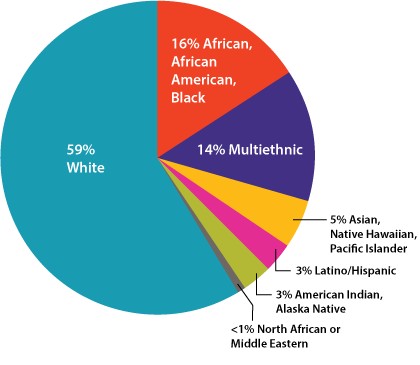

- They include a significant percentage of characters of color.

- They are filled with three-dimensional main characters.

- They are written and illustrated by too few people of color.

In summary, even with the deck heavily stacked against us, 41% of the books in the Collaborative Literacy suite are about people of color and there is an even split among male and female main characters. These characters are consistently represented as three-dimensional. This is important because it doesn’t help much to have good minority representation and gender balance if all the familiar stereotypes are simply reinforced by that representation. And unfortunately, not enough of our books are by authors and illustrators of color, which reflects the publishing industry at large. (According to the CCBC, just over 8% of the books in 2014 were written or illustrated by a person of color.)What can we do better? As for me, I will seek out more books about people of color and will specifically look for those about the several populations that are less well represented-notably, North African and Middle Eastern, which are nearly nonexistent (see the above pie chart). I will be far more alert to who wrote and illustrated the books we bring in to the office, vocally requesting that publishers send more books by, and about, people of color. As our diversity review team looks toward future book reviews, we’ll be thinking about the best way to collect data on disability, gender, and sexuality.

Finally, I think it’s important to note something that cannot be captured by the data alone. Our developers selected these books because they were making the best literacy programs possible, and not in order to meet external goals or to check a box on a form. They know that the kids in all classrooms deserve to be recognized for who they are and how they live. Books that reflect the world ensure that reading experiences are relevant, classroom discussions are richer, and the school community is stronger.

“For all of our differences, we are one people and we can either choose to live separately and in exile from each other or we can choose to live in belonging. When other cultures are familiar, then the possibility exists for our children to live in a post-racist society. I sincerely believe that literature can be a powerful tool for human understanding.”

Most adults in the U.S. spend their formative years in elementary school classrooms. It is their introduction to community outside the family and to the world. It is the breeding ground for much of the empathy and enmity we carry around as adults. A teacher, a friend, a book, can be transformative. As much as possible, we want to pair thoughtful materials that respect the art of teaching with children’s books that respect the beauty and range of humanity. Then maybe, through literacy and an embrace of diversity, we will do our (small) part to change the world.