As a body of research, the Science of Reading is intended to inform education stakeholders about how proficient reading and writing develop. Public discourse, particularly in social media communities, demonstrates the polarized stances and firmly rooted beliefs that, at times, water down or entirely misconstrue the Science of Reading (SoR) research.

In this blog, we unpack four common misconceptions that occur in SoR conversations. For each misconception, we offer a clarifying takeaway and provide further elucidation with research-aligned examples from our work at Collaborative Classroom, namely the Being a Reader™, Second Edition K–5 Tier 1 program and its instructionally aligned intervention program, SIPPS®.

Before we dig into misconceptions, it’s important to note that in the SoR community, we regularly reference two theoretical models: Gough and Tunmer’s Simple View of Reading (1986) and Dr. Hollis Scarborough’s Reading Rope (2001). Both notable for their contributions to the SoR, these models function under the premise that learning how to read is not a natural process, and they emphasize the importance of quality, comprehensive instruction. These models also identify two overarching domains of literacy skills (and subskills): word recognition and language comprehension.

Misconception 1: The Science of Reading is limited to the acquisition of foundational skills, specifically phonics.

Often SoR conversations focus on phonics, specifically on the development of word recognition in the primary grades. This is likely because widespread approaches to word recognition instruction are not aligned to the research, with disastrous impact on student reading proficiency.

While phonics development is essential in learning how to read, this conversational overemphasis is misleading. The Science of Reading extends well beyond the role of phonics in word recognition, and SoR advocates agree that research does not support a phonics-only instructional approach. In fact, the most effective literacy instruction draws from the wealth of research on all the essential components of word recognition and language comprehension acquisition.

The key takeaway

All students benefit from comprehensive literacy instruction, which includes explicit, systematic phonics instruction along with instruction in the other components of reading: oral language development, phonological awareness, vocabulary, comprehension, and fluency.

The Reading Rope model helps us to identify the comprehensive set of skills and subskills that are required to develop readers.

From research to practice: Examples from Collaborative Classroom’s approach

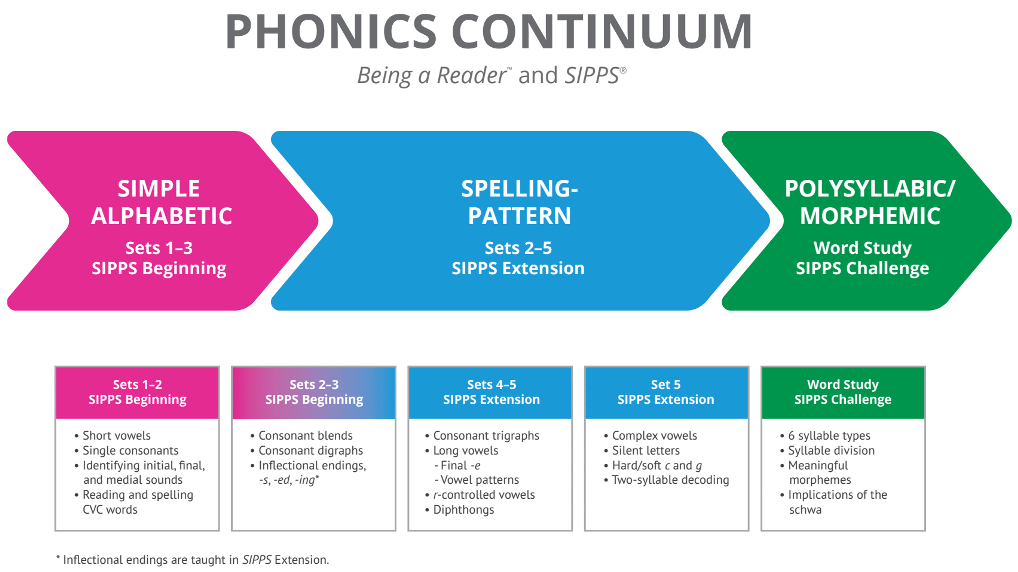

What might this look like in practice? Let’s examine the specific components of reading instruction in the Tier 1 Being a Reader program to see how research-aligned reading instruction is not limited to phonics. Just as we are able to draw on the Reading Rope Model to identify the skills that our instruction should address, we can also draw from the following graphic from Being a Reader, Second Edition.

In this table, the components that are essential to comprehensive instruction (components are listed across the top) are identified, along with instructional strands that support each component. This illustrates the comprehensive design of the program.

| Instructional Strands | Decoding and Word Recognition | Language Comprehension | Reading Comprehension | Writing and Spelling |

| Reading (K-5) | Phonological and phoneme awareness, phonics, fluency, high-frequency words | Syntax, concepts of print, variety of genres, discussions about texts | Reading strategies, texts on related topics, metacognition | Reading-writing connections to deepen knowledge |

| Small-Group Reading (K-2) | Phonological and phoneme awareness, phonics, fluency, decoding (alphabetic principle and spelling-sound correspondences), high-frequency words | Variety of genres, discussions about texts | Reading strategies, metacognition | Application of known spelling-sound correspondences to writing |

| Book Clubs | Variety of genres, discussions about texts | Reading strategies, metacognition | Reading-writing connections to deepen knowledge | |

| Vocabulary/Word Study (K-5) | Syllable types, word analysis, decoding polysyllabic words | Tier 2 and 3 words, word learning strategies, morphological awareness, figurative language | Tier 2 and 3 words, word learning strategies, morphological awareness, figurative language | Application of known spelling-sound correspondences to writing |

| Letter Names (K) | Letter recognition | |||

| Handwriting (K-1) | Letter recognition | Posture, hand strengthening, grip, letter formation | ||

| Independent Work (K-2) | Fluency, phonics, phonological awareness | Syntax and vocabulary acquisition | Independent reading | Handwriting, reading-writing connections |

Misconception 2: The only type of instruction aligned with the Science of Reading is direct instruction.

In this misconception, the term “direct instruction” refers to explicit, systematic, teacher-directed instruction. Much like the first misconception, we see extremes in application on either end of the continuum: on one side, advocating for a strict discovery approach to learning, and the other advocating for direct instruction only.

In truth, research supports the use of different instructional formats for different purposes; the content and level of student mastery should be taken into account when selecting an instructional approach. An abundance of research supports direct instruction as necessary for teaching students new to a skill set or body of knowledge, and for students who have demonstrated the need for additional support to achieve mastery. Foundational skills, for example, are sequential, require multiple practice opportunities for mastery, and are unlikely to be “discovered” by a student in a linear or time-efficient manner (if at all), so direct instruction is ideal. In contrast, instructional formats such as independent work do not require ongoing direct instruction, yet students develop key skills as they engage in self-selecting tasks, working responsibly, and managing themselves.

The key takeaway

Comprehensive literacy instruction will include a mix of instructional formats, including but not limited to direct instruction in whole-class, small-group, and independent work settings.

From research to practice: Examples from Collaborative Classroom’s approach

Direct instruction of foundational skills occurs in the small-group setting, specifically in Being a Reader’s Small-Group Reading Sets 1–5, where it can be differentiated to meet the needs of the group. This is evident in the instructional cues that are used to ensure the use of direct, explicit, and systematic routines.

From a comprehensive perspective, however, direct instruction is not used exclusively. Whole-class instruction includes teacher-led discussions and collaborative discussions among students as they navigate various components such as independent work, shared reading, read alouds, and vocabulary, to name a few. This variety provides ample experiences for students to learn new skills, practice and apply them—with and without teacher support and peer support—and demonstrate their learning.

Misconception 3: High-frequency words must only be taught with a phoneme-grapheme mapping technique.

High-frequency words are the words that occur most often in written English; they occur frequently and often have irregular spelling(s). The term high-frequency word is often used synonymously with sight words, but there is a difference.

We want all words to become sight words—meaning that we want these words to be immediately recognized on sight. Mastery of a word upon recognition makes that word part of the reader’s sight vocabulary.

There is much controversy around the instruction for high-frequency words; we only need peruse SoR social media groups briefly to find many teachers asking if the only “right” way to teach high-frequency words is to identify the “regularly” spelled portions of the word through a phoneme-grapheme mapping technique. While this method is well-regarded in the field, it requires a significant amount of instructional time, and research does not support the idea that this is the only way to achieve high-frequency word mastery.

The key takeaway

High-frequency word instruction should include explicit introduction of new words, and regular practice so that students efficiently learn to recognize the word(s) by sight.

From research to practice: Examples from Collaborative Classroom’s approach

The design of Being a Reader is intentional in teaching a handful of high-frequency words in the first several weeks of shared reading lessons.

In Kindergarten specifically, this design is intended to get students ready for small-group instruction. Since Kindergartners have yet to master many spelling-sound correspondences, these words are explicitly introduced and practiced so that students are able to recognize them by sight. This allows students with minimal spelling-sound correspondences to successfully engage in reading the controlled text provided in Small-Group Reading Set 1.

Beyond the shared reading lessons (identified in the graphic), the introduction of high-frequency words occurs in the small-group setting and follows a systematic progression guided by the program scope and sequence.

| Week 3 | the, and, is |

| Week 4 | I, see, a, you, me |

| Week 5 | we, are |

| Week 6 | can |

High-frequency words are introduced and reviewed using an explicit instructional routine, which prompts students to read, orally spell by letter name, and then reread each word. The routine focuses students’ attention on 3 critical features as they engage with the word: all the letters, in sequence, from left to right. This routine holds students accountable by requiring them to look at the entire word before reading it, while the repetition helps each word become a sight word. Additionally, the routine is designed to be highly efficient. This efficiency helps make space for the larger instructional sequence to occur (i.e. the remaining routines from the small-group lessons).

Spelling-sound correspondences that students have mastered may be incorporated into the established spell-out strategy (read-spell-read routine). Instructional guidance is provided to help determine how and when to offer this additional support.

Misconception 4: Students should exclusively read highly controlled, decodable text.

Much like the conversational overemphasis on phonics, many SoR conversations focus on “decodable” text, with a concerning absence of attention to the text’s connection to a systematic scope and sequence of phonics instruction, or consideration of differentiation based on student skill mastery.

The key takeaway

There is a time and place along the developmental continuum of learning to read in which highly controlled decodable text is appropriate and necessary as a temporary scaffold.

From research to practice: Examples from Collaborative Classroom’s approach

In our work, decodable text is used for word recognition skill application and practice with students in the early phases of word recognition acquisition, with huge benefits as a temporary scaffold.

Developing the knowledge and skills needed to be able to read with automaticity and understanding takes time; to further explain this, we lean on Linnea Ehri’s research in our work. Ehri proposes that beginning readers go through four phases of word recognition as they develop into proficient readers (1995; and later, Ehri & McCormick expanded to include a fifth phase, 1998). Reading behaviors that students are likely to demonstrate are identified for each phase, which helps educators determine instructional next steps and corresponding types of texts to support students’ skill mastery. The phases set a progression of text for students to experience as they develop their reading skills.

Generally, this progression introduces decodable texts aligned with the scope and sequence of phonics instruction as a means to practice spelling-sound correspondences and high-frequency words learned in isolation in connected text. As students gain phonics skill mastery, they shift away from highly controlled decodable texts and instead engage in reading a wide variety of complex texts that are culturally and linguistically varied and explore high-interest topics that will deepen background knowledge.

Conclusion

We hope you’ve found this exploration of common misconceptions about the Science of Reading useful. Our goal has been to avoid the polarizing stances and “hot takes” that can short-circuit meaningful discussions about the SoR and what the research says. As literacy educators committed to achieving reading proficiency for every student, each of us is on a journey of learning that requires patience, thoughtful conversations, and deep engagement with the research, especially when that research challenges our long-standing practices and ways of work.

***

For more about this topic, access our on-demand webinar Common Misconceptions About the Science of Reading.

Related Reading:

Dispelling Tier 1 Misconceptions, with Dr. Stephanie Stollar and Linda Diamond