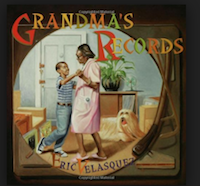

Children’s books are the cornerstone of many of Center for the Collaborative Classroom’s (CCC) programs; in a way, the authors are our behind-the-scenes collaborators. We want teachers, administrators, students, and parents to be able to get to know these wonderful authors and illustrators, so we are launching a new series of interviews, beginning with author and illustrator Eric Velasquez. His book Grandma’s Records is part of our Being a Writer program, and Journey to Jo’burg (which he illustrated) is included in our Individualized Daily Reading library.

CCC: I understand that your mother encouraged your drawing when you were young. Could you talk about how she supported your interest in art? How do you think your childhood influenced your work in children’s literature?

Eric Velasquez: My mother always kept me well supplied with art materials. After I received my first set of colored pencils from my grandmother, my mother brought home a set of watercolors. I created many watercolor paintings, some of which she would frame and display in our apartment in Spanish Harlem. I had a very rich childhood filled with many artistic influences. As detailed in Grandma’s Records, musicians would constantly visit my grandma. As a child, this was special to me because I was able to see creative people who looked like me. When Rafael Cortijo was coming to visit, along with Sammy Ayala and Ismael Rivera, my grandma sat me down and explained a few things. First of all, you will not address Rafael Cortijo as Cortijo. You will not address him as Rafael. You will only address him as Maestro because that man is a musical genius, and he deserves to be respected.

How can a child not be influenced? I remember to this day what they wore and how well mannered and polite they were. Most of all, they shared their gift with us by spontaneously breaking into song, singing about how delicious Grandma’s food was, complete with details. Years later in school when we learned about the musical genius Beethoven, I remember thinking quietly to myself, I know a musical genius. Ultimately, I have always seen myself as an artist. I have always been creative and sensitive. The reason I am drawn to children’s literature is because my mother read to me as a child. Many times I would look at the books by myself. Spanish was my first language. Therefore, deciphering the pictures and extracting the story was a magical process for me.

CCC: What were some of your favorite books as a child?

Eric Velasquez: I had lots of books as a child. However, there were two books by Brinton Turkle that were very special to me: The Lollipop Party (illustrated by Turkle) and The Sky Dog (written and illustrated by Turkle). Both books feature a boy that appears to be brown. These were the only representations of a child of color that I had in my collection. Besides those two books, I loved comic books.

CCC: Kindergarten and first-grade students are emergent writers, so we incorporate drawing into the early grades of our Being a Writer program. The students’ first narratives are primarily visual. Could you share your experiences with drawing in elementary school? On the flip side, have you ever taught drawing to children?

Eric Velasquez: Because I was a reluctant reader, I was placed in Group C. While the rest of the children in Groups A and B would read, those of us in Group C were free to pretty much do whatever we wanted to do as long as we were not a distraction to the rest of the class. The teachers did not seem very concerned with us, therefore I spent my time drawing. In the fifth grade, however, my art teacher, Ms. Mondevan, recognized my talent and began to nurture me as an artist. For the first time, I was accepted as an artist somewhere other than in our home. This was life-changing. Ms. Mondevan seemed genuinely interested in my artistic development. She allowed me to work on projects independently of what the rest of the class was doing, and, as a result, the other students and the faculty began to regard me as an artist. Suddenly I was an artist outside of the house as well as inside of it. I have conducted many drawing workshops for children. I also conducted workshops with the Hudson River Museum in conjunction with the Jerry Pinkney exhibit a couple of years back, in which I taught children how to paint in watercolor. I found the experience very rewarding and a lot of fun. Some parents would sit off to the side and allow their children to fully engage in the whole experience of working in watercolor. However, it was remarkable to see how other parents would constantly intervene and not allow their children to fully engage in the creative process of discovery. They would tell them that their artwork was the best in the class and this would distract the children, keeping them from completing the project. Yet watching those who quietly discovered watercolor on their own, unafraid of making mistakes and fully open to the possibilities of mark-making, was perhaps the most enjoyable part of that workshop.

CCC: Could you tell us about a favorite elementary school teacher?

Eric Velasquez: There are three teachers who were the most influential. First, there was my third-grade teacher Ms. Holmes. She taught us about notable African-Americans including Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, and Marcus Garvey, and educated us about Africa. Second, as I mentioned, was Ms. Mondevan, my art teacher in the fifth and sixth grades. And third was Miss Langston, my sixth-grade teacher, who encouraged me to read more books and treated me as though I was very smart. Her impact on my life was profound because she would say things like, When you go to college you will discover”|

as if there was no doubt in her mind that I would be successful.

CCC: You’ve illustrated many books written by others; what is it like to illustrate someone else’s story? Tell us about the transition to illustrating your own stories.

Eric Velasquez: I really enjoy illustrating the words of other writers. I try to find myself in the stories that I illustrate, and sometimes I try to develop a subtext in the artwork that runs concurrent to the narrative. This is what I believe makes me a storyteller. I first ask myself, how does this manuscript relate to me? Then I ask, what do I want to say with the story? Then I begin to develop a subtext. In many ways that is the engine that drives the train, for without this deeper layer the images would be flat interpretations of the story. When I am illustrating my own stories, I first write the manuscript, then I imagine that the story was written by another author and I begin to illustrate.

CCC: When you wrote and illustrated Grandma’s Records, how did the story emerge-first in language or in images?

Eric Velasquez: Grandma’s Records began as a story that I told my friend Keith Henry Brown after he had given me a gift-a CD entitled the “Buena Vista Social Club.” He gave me the CD stating that this was brand-new music from Cuba. I told him that I was familiar with most of the songs because I used to spend summers with my grandmother listening to old records. He seemed fascinated by my story and asked me to repeat it to him several times. Eventually, I had to write it down. Therefore the story came first and the images came later.

Eric Velasquez: Grandma’s Records began as a story that I told my friend Keith Henry Brown after he had given me a gift-a CD entitled the “Buena Vista Social Club.” He gave me the CD stating that this was brand-new music from Cuba. I told him that I was familiar with most of the songs because I used to spend summers with my grandmother listening to old records. He seemed fascinated by my story and asked me to repeat it to him several times. Eventually, I had to write it down. Therefore the story came first and the images came later.

CCC: I read that what you find most gratifying in your illustration work for children is the ability to impact the future through art.

You went on to provide an example of working from a text that indicated a beautiful woman and choosing to paint a dark-complexioned African woman, thereby broadening the spectrum of beauty that children see. You stated that most Americans have no idea what it is like not to see themselves represented in books or films.

Your message really resonated with me (and I think you have the name of an organization in the making: “Impact the Future through Art!”). An important discussion is taking place about the lack of diversity in children’s literature and within the publishing industry itself. At Collaborative Classroom, we try to balance images of gender, race, family configurations, and geography so that many different students see themselves in the books we select for our programs. That said, I know we can do better. What are your thoughts on this topic, both as an individual and as an artist within the children’s publishing world?

Eric Velasquez: First of all let me state how flattered I am that you have quoted me in this question. This is a topic that I am very passionate about and that I frequently discuss with my illustrator friends. The notion of inclusion and diversity is very complex in America. I believe every art creator has an agenda. There are all sorts of agendas, especially in children’s books. From the princesses to the dragons to the stories themselves, sometimes it seems like I have been looking at the same books for fifty years. The princess, curiously enough, always looks the same: why is that? Moreover, it is time that Americans learn to see others as the heroes of stories. It is not realistic or healthy for Americans to always see themselves as the main protagonist. It distorts their view of themselves and of others.I believe that there is a definite reason why there is a lack of diversity in children’s books today. Once a child sees himself represented in a book, his existence is validated, and he feels that he is part of the world. Conversely, when a child does not see herself represented in books, she doesn’t feel as though she is part of the world, and her life, her existence, is not validated. I was a reluctant reader because I did not see enough images that looked like me in books. When I discovered comic books, I loved reading issues of the Avengers because one of the members of the Avengers was a character called the Black Panther. The character’s name was T’challa, and he was an African prince-a brilliant tactician, strategist, scientist, tracker and a master of all forms of unarmed combat-and I imagined I could be a member of the Avengers. Curiously enough, the Black Panther has not been featured in any of the movies yet. (Impacting the future through film.) When the question, why is it important to exclude people of color from books? is asked, then we can address why diversity and inclusion are necessary.

“Once a child sees himself represented in a book, his existence is validated, and he feels that he is part of the world.”

CCC: An important element in Collaborative Classroom’s literacy programs is the process of sharing work and listening to what others have to say about it; it’s one facet of what we call a Collaborative Classroom. We work hard to create a supportive environment so students feel safe enough to take risks with their own work and know how to respectfully communicate their opinions about others’ work. Do you have a community of artists? If so, do you seek each other’s feedback? What advice do you have for young writers and artists who might be afraid to share their work?

Eric Velasquez: Many of my friends are illustrators, and we are constantly communicating with each other either by phone or internet. Occasionally we will ask each other for feedback, but not as often as you might think. The advice I would give a young writer or artist who might be afraid to share their work is, first examine the source of the fear. What exactly is the student afraid of? Among my own students at FIT (the Fashion Institute of Technology), I find that the answer is usually fear of teasing by the other students or the fear that the work is not good enough or will not be the best in class. Therefore I try to convince them that telling their story is more important than being teased or trying to be the best.

CCC: You have an extraordinary ability to convey a character’s essential being. Time and again, you reveal their humanity through facial expression, body movement or position, and setting. How do you do this?

Eric Velasquez: When I was a child, most of the images I saw of people of color were caricatures and stylized images. It was easy to accept this notion. However, when I saw the [Velázquez] painting of Juan de Pareja, the realism of it began to haunt me. Over the years that painting has had a profound effect on me. What I saw in that painting is what I strive for in my work today.

Eric Velasquez: When I was a child, most of the images I saw of people of color were caricatures and stylized images. It was easy to accept this notion. However, when I saw the [Velázquez] painting of Juan de Pareja, the realism of it began to haunt me. Over the years that painting has had a profound effect on me. What I saw in that painting is what I strive for in my work today.

CCC: In many of your picture books-at least the ones I’ve read recently-characters navigate and embody two vastly different worlds. For example: Monsieur de Saint-George in The Other Mozart (born to a slave mother on a sugar plantation in the Caribbean and raised among the 18th century French aristocracy in Paris); Naledi’s Mma in Journey to Jo’burg (lives and works in a wealthy white-only neighborhood in Johannesburg far from the small village where her own family lives); your grandmother in Grandma’s Records (longs for her Puerto Rico home and lives in New York City). I could go on! How has your life influenced your choice of book projects, and how have your book projects influenced your life? Are there certain books and themes that particularly resonate with you?

Eric Velasquez: Once again I am impressed by your question. My life has influenced my work in a great many ways. Growing up, I had to live in two different worlds; we were Afro-Puerto Rican and we were African American. Living and being part of those two worlds sometimes made me see the absurdity of America where labels seem to define you. However, it is as though the label maker has only four labels for 400 varieties of people of color. It is a choice one has to make being a person of color: you either define yourself or allow others to define you based on their preconceived notions. The stories I like to tell are about people who, in one way or another, reject the labels and limitations others place on them and forge their own identity. My book projects have literally changed my life. One of the aspects that I enjoy most about my work is that it allows me to be a lifelong learner. Historical nonfiction book projects are like the gift that keeps on giving for me.

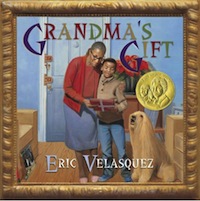

Eric Velasquez: Once again I am impressed by your question. My life has influenced my work in a great many ways. Growing up, I had to live in two different worlds; we were Afro-Puerto Rican and we were African American. Living and being part of those two worlds sometimes made me see the absurdity of America where labels seem to define you. However, it is as though the label maker has only four labels for 400 varieties of people of color. It is a choice one has to make being a person of color: you either define yourself or allow others to define you based on their preconceived notions. The stories I like to tell are about people who, in one way or another, reject the labels and limitations others place on them and forge their own identity. My book projects have literally changed my life. One of the aspects that I enjoy most about my work is that it allows me to be a lifelong learner. Historical nonfiction book projects are like the gift that keeps on giving for me. Often while researching a person for one of my projects, I discover something that has little to do with what I am researching, and by the time I am finished reading I have figured out a way of incorporating that topic into the project. Or I will begin to create a new project inspired by what I learned. Sometimes what I discover is very profound, and other times it just helps fill in the contextual details. Most significant was the research for Grandma’s Gift. I decided to go to Puerto Rico to get back in touch with my roots. I visited the site of my grandmother’s home in Santurce and looked up my family history on ancestry.com. I traced my family back to 1860 and found the name of my grandmother’s grandmother, which was an awesome discovery because I also learned that all of my people were literate (according to the census). This confirmed what my grandmother told me again and again. She also spoke of how many people who came to Puerto Rico in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were from different countries in Europe and how a lot of them could not read or write. This information was not available in any school history book, therefore I could not confirm it until recently when it was all confirmed and documented in Henry Louis Gates’ Black in Latin America, both the PBS special and the book. Yes, I discovered all that while researching Grandma’s Gift.

Often while researching a person for one of my projects, I discover something that has little to do with what I am researching, and by the time I am finished reading I have figured out a way of incorporating that topic into the project. Or I will begin to create a new project inspired by what I learned. Sometimes what I discover is very profound, and other times it just helps fill in the contextual details. Most significant was the research for Grandma’s Gift. I decided to go to Puerto Rico to get back in touch with my roots. I visited the site of my grandmother’s home in Santurce and looked up my family history on ancestry.com. I traced my family back to 1860 and found the name of my grandmother’s grandmother, which was an awesome discovery because I also learned that all of my people were literate (according to the census). This confirmed what my grandmother told me again and again. She also spoke of how many people who came to Puerto Rico in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were from different countries in Europe and how a lot of them could not read or write. This information was not available in any school history book, therefore I could not confirm it until recently when it was all confirmed and documented in Henry Louis Gates’ Black in Latin America, both the PBS special and the book. Yes, I discovered all that while researching Grandma’s Gift. After completing 30 picture books, I realized how much my views and opinions have changed over the years, many of them intensified by my work. A good number of the books I have illustrated deal with racism on one level or another. It is hard not to be affected by all of the information. However, at the end of each day, I continue to marvel and admire the people of African descent who have endured and still endure so much hatred, yet are still able to achieve such amazing and beautiful things in all areas of human existence.”

After completing 30 picture books, I realized how much my views and opinions have changed over the years, many of them intensified by my work. A good number of the books I have illustrated deal with racism on one level or another. It is hard not to be affected by all of the information. However, at the end of each day, I continue to marvel and admire the people of African descent who have endured and still endure so much hatred, yet are still able to achieve such amazing and beautiful things in all areas of human existence.”

CCC: Is there anything else you’d like to share?

Eric Velasquez: Yes, an excerpt from an essay I wrote for the International Reading Association earlier this year:

Why Was I a Reluctant Reader?

It would take me 30 years to answer that question. One of the problems was the reading material. Consistently not seeing myself represented in the reading material was a big turnoff. Worse was the fact that the few times I did see people of color in any books they were usually portrayed as slaves drawn as caricatures. All of the children in my elementary school were African American or Latino. Our textbooks were filled with all types of stories-some had an urban setting, however, the images consisted of an all white cast. Oddly enough, some of the children from Latin America identified with the white characters in the stories (especially with the abridged version of Huckleberry Finn). Not only did it inspire them to read the stories but especially if the character was doing something cool, they would show off and say “That’s me,” even though the character in the book at times was blonde. If you were a child of African descent and attempted to do the same (“That’s me” bit ) the other children would ridicule and torment you with “That is not you, you are black!” Why did they take such joy in reminding me that I could not engage in the same fantasy as they did? While drawing during reading time in Group C, I would often think one day I am going create a story and it is going to reflect my world, my neighborhood, my parents, my friends, and my people. Someday a white child will read my story and say, “That’s me” when he looks at my image and no one will torment him.

“I would often think one day I am going to create a story and it is going to reflect my world, my neighborhood, my parents, my friends, and my people.”

One of the most rewarding experiences of being an author/illustrator is offering children the opportunity to create their world. I have been conducting workshops in elementary schools on how to create a book dummy for about five years now with amazing results. A book dummy is a sample of a book usually bound and hand drawn with the text and the sketches in place, a fully paginated version of a story. The purpose of the book dummy is to give the editor and art director an idea of what the finished book will look like. Most book illustrators create a book dummy before creating the finished artwork for their books. Prior to my school visit, children write an autobiographical manuscript of about 450 words or less. By not limiting the children to write only about their family, some children write about their friends or their sports activities, and some children even write about their pets. On the day of the workshop, I assist the children in constructing the book dummy. I show them how to design a cover for their book; how to portion and divide their manuscript; how to cut and paste their text into the book dummy; and lastly, I assist the children in drawing the images. However, usually at this point they are off and running. The workshop concludes with the children reading their stories out loud, sharing their world with their classmates and teachers.