What does evidence-based vocabulary instruction look like in practice? This two-part blog series draws inspiration from Dr. Isabel Beck’s seminal book Bringing Words to Life: Robust Vocabulary Instruction. In this first installment, we unpack three key recommendations from Dr. Beck’s approach to teaching vocabulary in grades K–2 and draw connections from research to classroom practice, using examples from Collaborative Literacy.

“It is clear that a large and rich vocabulary is the hallmark of an educated individual.”

Bringing Words to Life: Robust Vocabulary Instruction by Dr. Isabel Beck

“Words are, in my not-so-humble opinion, our most inexhaustible source of magic.”

Albus Dumbledore in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows by J.K. Rowling

Introduction: The Joy of Robust Vocabulary Instruction

In the tumultuous world of education, where it often seems the issues upon which we can all agree are few and far between, vocabulary instruction might rise above the fray as a topic that unites more than it divides. In fact, robust and evidence-based vocabulary instruction can be joyful, even magical.

What teacher wouldn’t want to inspire students to be like Jerome, the child who delights in acquiring a multitude of words in The Word Collector by Peter H. Reynolds? Is there an educator who wouldn’t be thrilled to hear his student describe how ecstatic she was to have adopted a new puppy? Or to see a student use the word baffle, first encountered in a read-aloud, in his personal narrative about attempting to learn a magic trick?

Educators around the world have been inspired and guided by Dr. Isabel Beck and her seminal work on the essential role that vocabulary instruction plays in helping students become literate individuals. Novice and veteran teachers alike find her book Bringing Words to Life: Robust Vocabulary Instruction full of creative, research-based ideas for teaching, reinforcing, and assessing vocabulary.

From Research to Practice

Collaborative Classroom recently hosted a book study discussion about Bringing Words to Life. In our discussions, educators delighted in Dr. Beck’s observation that a class of fourth graders “went absolutely wild with bringing in words” after their teacher “set up a system called Word Wizard, in which students [gain] points by bringing in evidence of hearing, seeing, or using target words outside the classroom” (p.111).

Read on as we discuss three recommendations from Dr. Beck’s approach to teaching vocabulary and illustrate them using specific, aligned examples from Being a Reader and Being a Writer instruction at grades K–2.

The influence of Dr. Beck’s evidence-based, teacher-friendly approach to vocabulary instruction is apparent in Collaborative Classroom’s pedagogy and programs—specifically in the vocabulary instruction found in Being a Reader™, our comprehensive reading curriculum, and Being a Writer™, our comprehensive writing program, which together comprise our K–5 ELA suite, Collaborative Literacy.

Introducing Words to Young Students

Dr. Beck is a proponent of robust vocabulary instruction that “involves directly explaining the meaning of words along with thought-provoking, playful, and interactive follow-up” (p. 3).

Dr. Beck is a proponent of robust vocabulary instruction that “involves directly explaining the meaning of words along with thought-provoking, playful, and interactive follow-up” (p. 3).

In addition, she advises that instruction should focus on Tier 2 words that students are unlikely to use but that educated adults regularly employ in speech and writing (p. 9). The Being a Reader curriculum adheres to this approach by:

1. Providing explicit instruction in a set of carefully chosen, high-utility Tier 2 words that are introduced in context.

For example, in a Grade 1 unit on visualizing using poetry and fiction, students are taught the word “frigid” after being exposed to it during a read-aloud of The Snowy Day by Ezra Jack Keats.

Word cards are used when providing vocabulary instruction.

2. Providing student-friendly definitions and examples of word use.

Students learn that “frigid” means almost the same thing as cold. However, it is not just a little cold, it is very, very cold!

The teacher shows the cover of the book and points out that Peter, the book’s main character, is dressed in warm clothes because it is a frigid or very, very cold day.

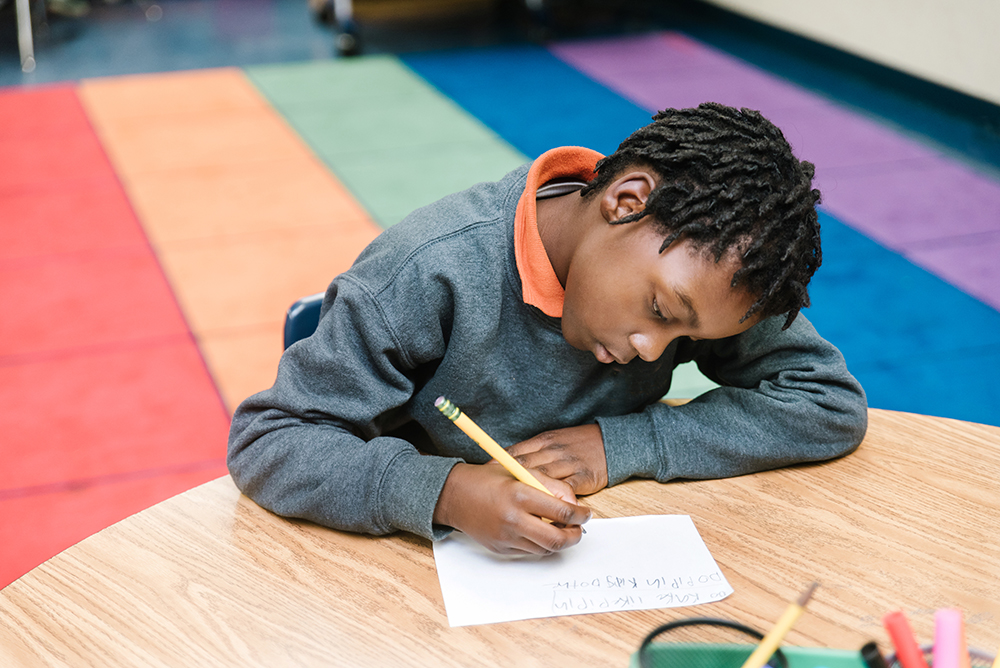

3. Creating opportunities for active engagement with the words.

Students are invited to discuss the word frigid, such as by responding to the question, “What would you wear to school on a frigid day?” or “What would you do if you woke up and your bedroom was frigid?”

Later, in a review of the four new words taught during the week, students play the game “Which word am I?” The teacher provides a clue about one of the week’s words, and students have to figure out which word best fits the clue and explain why.

Maintaining Attention to New Words

Dr. Beck urges teachers to include a “record of the words being learned” in their classroom (p. 109). Being a Reader supports this ongoing attention to words by providing picture cards and word cards for students to reference as they build their vocabulary over the course of the year.

Being a Reader also sustains student focus on vocabulary through cumulative review activities each week.

Being a Reader also sustains student focus on vocabulary through cumulative review activities each week. By revisiting words taught in previous lessons, students are invited to find ways to include new vocabulary in their ongoing conversations, to seek out these words in new texts they read, and to incorporate these words in their own writing.

In addition, extension activities are provided to promote deeper understanding of different vocabulary words. In a Grade 1 unit on using text features in nonfiction, students learn the words “favor” and “interview” in the read-aloud Throw Your Tooth on the Roof: Tooth Traditions from Around the World.

Subsequently, they have an opportunity to interview classmates to find out what they favor using the sentence frame “Which ____ (sport/color/food) do you favor? Why?”

Connecting Vocabulary to Writing

Vocabulary is just as crucial in writing instruction as it is with reading instruction. Learning vocabulary can often seem like the same thing over and over; you learn a word just long enough to forget it. Vocabulary is difficult for students to master, but incorporating vocabulary into writing instruction can help students retain words.

Isabel Beck asserts that “…to affect writing the [vocabulary] instruction has to be robust”(p.151). Vocabulary instruction shouldn’t be just drill and kill; students should see application.

For instance, a teacher might display a word wall for students to refer to when they are writing, or students could keep track of words in a journal/notebook throughout the year. This reduces the potential of students seeing vocabulary as simply something to memorize for a test. Instead, new words can be incorporated into their writing on a daily basis.

The Being a Writer program affords opportunities for students to use new vocabulary through narrative, expository, opinion, poetry, and letter writing. As Beck recommends, the instruction itself is robust, with students gathering together on a regular basis to hear books and see how authors hone their craft. Students practice talking with their peers to generate words and sentences to use in their writing through peer conferencing. Students are also introduced to writing notebooks as a place to record the new vocabulary words they’re learning.

Conclusion

Vocabulary instruction is robust when teachers ask students to observe where they see words in real life, invite students to discuss the context of the words they are seeing, and challenge students to use those words in their own writing.

Whether you use a word wall or mentor texts to help students see how their own vocabulary can be extended into their writing, vocabulary instruction should be robust and not an exercise in rote memorization. With proper guidance, students will experience the magic of vocabulary in helping them become prolific readers and writers.